by

David B. Dodson

June 2018

Horses were a very valuable resource, if not the most important instrument in the Spanish conquest in the hinterlands of the New World. It was generally said that one horse soldier was worth more than two foot soldiers (Priestley, 1928, Padilla, 1596); for without the horse, the early Spanish in the countryside and forests would have been on equal footing in armament with the Native populations with both only having basic weapons including clubs, swords, knives, and bows and arrows. Actually, a well-trained Native archer could fire off more arrows in a minute than a Spanish crossbowman. Further, with a more superior population, the Natives would have been able to eventually fend off and overwhelm the Spanish through overwhelming odds. The horse made all the difference in Spanish superiority and would allow a reconnaissance party to double if not triple the overall amount of territory that could be traversed in a day, including returning back to the safety of the encampment. The records of the exploits of Cortez in the conquest of Mexico, Coronado in the American Southwest, and Soto in the American Southeast attest to this fact.

Thus, when the Don Tristán de Luna expedition left the port of Veracruz in New Spain in 1559, the eleven ships carried over 250 horses aboard for use by an army that had around 500 soldiers. However, horses do not survive well on long voyages, much less with a rationed water supply, and the Luna armada took a total of over 60 days to finally reach Ochuse. Thus, around 100 were lost in transit, having to be thrown overboard when their digestive systems failed and caused deaths.

Due to this attrition among the herd of horses on the Luna Expedition, the Spanish took approximately 150 horses to the Native village of Nanipacana on the eastern bank of the lower Alabama River in the fall of 1559 and the spring of 1560 when the Spanish relocated the main expeditionary force from Pensacola Bay (Ochuse). When the reconnaissance force departed Nanipacana to find Coosa on April 15, 1560, the settlement was then left with fewer than 100 horses. After the Native population had purposely denuded the land of edible vegetation for miles around Nanipacana, the people began to starve and die, and there is no doubt many horses met the same fate.

Many naval expeditions were sent up and down the rivers in search of foodstuffs, but most returned empty-handed. Therefore, on or about June 19, 1560, the situation was so dire that a junta, or serious meeting, was held amongst the Royal Officials, captains, and religious personages. Eventually Governor Luna was convinced to plan an abandonment of the inland settlement and relocate the people down to the Bahía de Filipina (today’s Mobile Bay). There, they believed they could temporarily survive on fish and shellfish that could be obtained along the shores of the vast bay, until more foodstuffs would arrive from New Spain.

The relocation was to be accomplished by rafting down the river, which indicated that perhaps there were not enough healthy horses for protection against the Natives, who would ambush them in the woods, and therefore not afford a safe overland route on the paths that skirted the river. Indeed, it is surmised that the colonists probably did not even have any shoes left to make the march, having eaten them for whatever nourishment the leathers might offer. Thus, in preparation for the tasks of building the rafts and energizing the weakened condition of the soldiers and desperate colonists, it was decided that the remaining horses would be systematically slain and eaten.

In The Luna Papers, it is recorded in early June 1560:

Meantime, our need grew to such extremity after a thousand difficult and laborious efforts to sustain ourselves, that horse-meat (carne de caballo) was publicly weighed out to give rations to the people, but not until for many days the most of us had had, not a handful of corn, which would have been like an abundance, but not even a few bitter acorns (Priestley II, 1928).

And by June 19, 1560, the situation had gotten even direr:

In the meantime, while this is being waiting the relief which this camp [Nanipacana] and people shall have from the necessities of the present, has been and must be considered, for twelve or fifteen days more the entire camp may parish or come to eating all the horses, which is the [only] recourse we have (Priestley I, 1928).

When time came to butcher the horses, it was Captain Bathazar de Sotelo who was the first to offer his four horses up for slaughter. Sotelo had been a conquerer in Peru in the 1540s and was one of the most experienced soldiers on the Luna expedition (Dodson, 2016). His immediate actions of offering up his personal horses exemplified his leadership capabilities.

Another history obtained from testimonies of returning Luna soldiers to Mexico City from la Florida offers some details in how the Spanish ate these horses. No part of the carcasses was wasted.

Establishing their place, and they were there without going forward nor back many days; the people were many, and the land was such as not to be able to provide supplies of foods, and those that they had brought had run out, that it then came to pass the greatest hunger ever was seen, and mortality, because they say that in standing men were falling dead of hunger, they ate the horses down to their hooves (uñas), until there was nothing left to lose (Dodson, 2016).

While the eating of horses at Nanipacana has been well-presented by historians in their narratives, there is another document found in The Luna Papers that also tells of the expedition eating the horses and mules at another time.

After the main expedition returned to the bay of Ochuse in August of 1560, there were no horses of note remaining. But by November 1560 the number of horses and mules found there—albeit very thin, weak, and practically useless—was around 50. They were mainly left over from the returning reconnaissance expedition from Coosa, which had purposely decided to never eat the horses because of their value and respect by the Native populations (Davila Padilla, 1596). However, by the end of December 1560 and into January 1561, the remaining soldiers began to cook their supply of cowhides and, to survive, once again began to eat all the remaining living horses and mules. One of the young, surviving soldiers of the events at Ochuse testified to the following:

The said dispatch having been sent to the viceroy, as has been told, all the people were waiting with the governor [Luna] in the port [of Ochuse] until they could see what the viceroy would send to order them to do, for a period of three or four months more or less, during which time they suffered greatly from hunger because they had come down from the [inland] settlements. They were reduced to eating the cowhides (cueros de baca) which had been brought from New Spain and all the horses (cauallos) that they had…(Priestley II, 1928).

In the many documents found in The Luna Papers, Viceroy Luis de Velasco writes Luna of his intentions to send many things, including more healthy soldiers and more horses to la Florida, but the correlation of the many documents we presently have cannot corroborate that the viceroy was able to accomplish all that he intended.

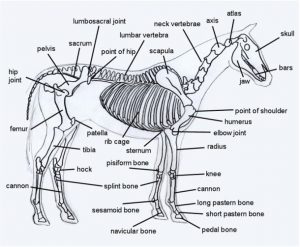

Thus, both at Nanipacana and Ochuse, one should be able to find “graveyards,” or trash pits, with a plentitude of horse and mule bones, skulls, and plenty of teeth…especially the teeth, which would not deteriorate even after 450 years (Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4). Also, if you did not have horses anymore, you would not be concerned about saving their iron shoes. Those would also become part of the archeological record (Figure 5).

Figure 1. Major bones of a horse.

Figure 2. Remnants of an unearthed horse burial at St. Augustine, Florida, ca. late 1700s. The bones of horses on the Luna Expedition would be found separated and perhaps carbonized after having been roasted upon a fire pit.

Figure 3. Mass burial of horse skulls from a Late Medieval house, Portmaramock, Ireland. This is perhaps how archeologists might find horse skulls at Santa Cruz de Nanipacana since they were all slaughtered at the same time.

Figure 4. Horse bones and teeth excavated from a sandy trash pit ca. 1700s found in the Roanoke Island area, North Carolina, 2011.

Also, worn out or discarded Spanish horseshoes and associated nails would probably be in the mix (Figure 5). (A subsequent article will address horseshoes on the expedition more fully.)

Figure 5. Horseshoe from Peru (ca. 1535) from the Spanish conquerors, similar to horseshoes found related to the Coronado Expedition to the American Southwest in 1540 and Spanish Expeditions into the American Southeast during the 1500s.

Conclusion

Horse bones, teeth, and shoes should be found at the Luna settlement site along the shores of Pensacola Bay. Likewise, the same equine remains should be found at the inland settlement site of Santa Cruz de Nanipacana on the eastern shore of the lower Alabama River. Also, there is a good possibility of finding a large, central area of skulls with teeth and horseshoes where all the remaining horses were slaughtered in late June of 1560 before the expedition left to relocate on the shores of today’s Mobile Bay. Further, anything equine related to the 1540 Soto expedition should be found on the west side of the lower Alabama River where the Spanish lost many horses to the arrows of the Natives in the battle of Mabila.

Sources

David Dodson, unpublished Luna manuscript and translations, 2016.

Agustín Dávila Padilla, Historia de la Fundación y Discurso de la Provincia de Santiago de México de la Orden de Predicadores, Madrid, 1596.

Herbert Ingram Priestley, The Luna Papers, Florida State Historical Society, DeLand, 1928.

Marc Simmons and Frank Turley, Southwestern Colonial Ironwork: The Spanish Blacksmithing Tradition, Sunstone Press, Santa Fe, 2007.

Coronado Expedition horseshoes: See https://www.psi.edu/about/staff/hartmann/coronado/helpscholars.html

[1] This article is taken from a much longer and in-depth manuscript concerning horses on the Luna expedition.

[2] http://www.equinespot.com/images/610xNxhorse-skeleton-illustration-lg.jpg.pagespeed.ic.NZLQa14VBI.jpg

[3] https://www.archaeology.org/images/horse-st-augustine-florida.jpg from an article in Archeology, June 9, 2015, found at https://www.archaeology.org/news/3388-150609-florida-dragoon-horse

[4] http://irisharchaeology.ie/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/horse-skulls-archaeology.jpg

[5] https://3.bp.blogspot.com/-QSIN-EgItVE/TajZIBUr4AI/AAAAAAAAEdc/AKAduHdiYfg/s320/Copy+of+horse+teeth+2.JPG

[6] https://www.archaeology.org/images/JA2016/Artifact/Artifact-Peru-Colonial-Horseshoe-Discovered.jpg, found in Archeology, June 13, 2016, https://www.archaeology.org/issues/224-1607/artifact/4565-artifact-peru-colonial-horseshoe