The Mystery of the Alabama Stone Site

by: Caleb Curren and Steve Newby

(Reprint from PAL Journal 2001; updated Jan. 2018)

On the eve of Alabama statehood in 1817, a large stone engraved with Latin inscriptions was found in the forest near Tuscaloosa. The stone evoked speculations then as it still does today. The first published report of the stone was in 1876 by Thomas Maxwell, a local Tuscaloosa landowner, who read his local history paper at a meeting of the Alabama Historical Society (Maxwell, 1876). A portion of the paper dealt with the Alabama Stone. Maxwell gives credit to professor Wyman of the University of Alabama for the original information concerning the stone. The following is the basic story as Wyman recorded it in his paper:

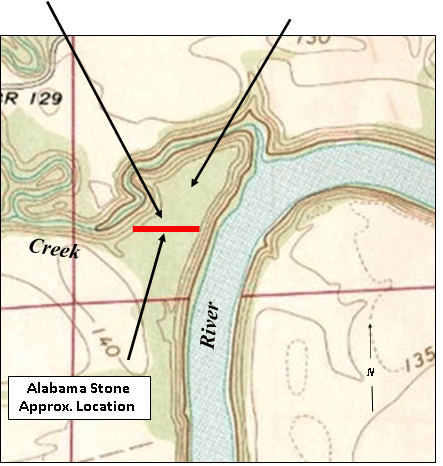

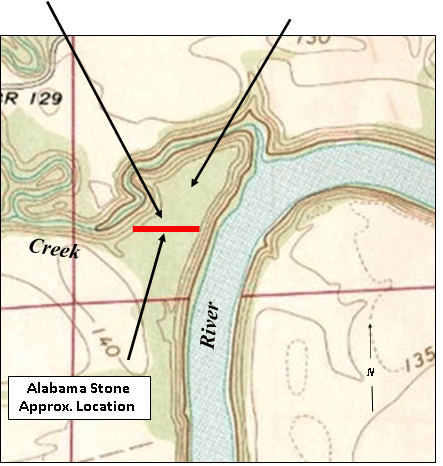

In 1817, Mr. Thomas Scales, a worthy citizen of the neighborhood, when a boy, removed with his father from North Alabama to the new settlement at Tuskaloosa falls. The first work they did was to clear a piece of ground. In clearing away the timber, they found an earthwork or embankment, in the nature of a fortification, which ran across the peninsula formed by the junction of the creek and the river (fig. 2). This embankment was about four feet high, and on the top of it, all the way across from river to creek, were growing the largest trees of the forest. At the foot of one of these (a large tulip tree, which stood on the very top of the embankment) they found a stone set up against the tree, with the lower end of the stone half buried in the soil. On the stone they discovered some curious letters, which being in Latin, they could not understand; and this, Mr. Scales said, induced his father to take the stone up to the settlement at the falls, now the town of Tuskaloosa, where it stood for a long time near to Squire Powell’s office, a subject of constant speculation for the curious. He remembered particularly (as he stood around it as a boy) to have heard the people say the inscription upon the stone was precisely the same as that upon the old Spanish dollar (Maxwell, 1876, pp. 79-80).

Figure 2: USGS topographic map of the Alabama Stone Site (1Tu280).

Possible defensive location?

ll of this information was taken from Mr. Scales (then an old man) by Professor Wyman. Scales died not long after. According to Wyman, Tom Scales was well respected around the community and his story was taken as the truth. The stone was kept near the door of the log cabin which was the office of Levin Powell, Tuscaloosa County’s first tax collector, until 1824 when it was given to Silas Dinsmore of Mobile. Dinsmore was a trustee of the American Antiquarian Society of Massachusetts and, as such, sent the stone to Boston. It was catalogued as “The Alabama Stone” and displayed as one of the earliest evidences of European exploration in the New World (Clinton, 1958, pp. 11-12). In the 1950’s Alabama citizens began to object to the fact that the “Alabama Stone” was not in Alabama and “suggestions” were made that it be returned (Stanley, 1953). The stone was returned and is now housed in the Alabama Archives and History in Montgomery.

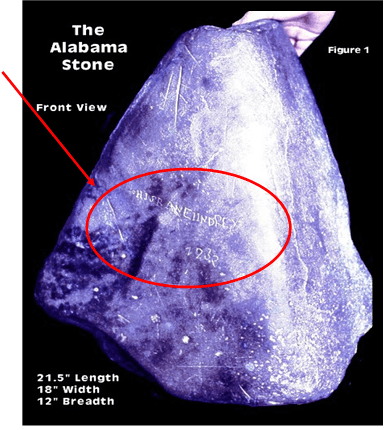

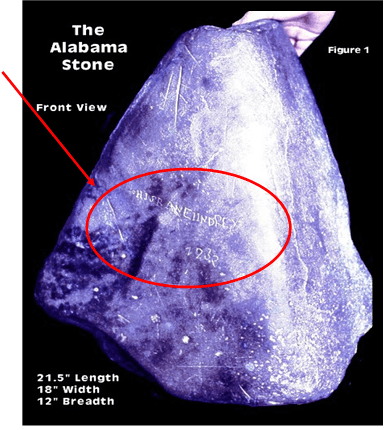

The stone is ferruginous sandstone and measures 21 1/2″ in length, 18″ in width, 12″ in breadth, and weighs about 200 pounds (figures 1 and 3). The general shape is “teardrop.” Over the surface of both sides of the stone are “gashes” and small conical holes. These configurations are seen frequently on stone found at aboriginal sites in the region. The “gashes” are assumed to have been made by Native peoples to use as edge sharpeners for ground stone tools. The conical holes are assumed to have been used as “holders” for (1) chert cobbles as they were flaked, (2) nuts as they were cracked, or (3) seeds as they were ground. The stone was probably used by Natives before and/or after the European inscription was carved upon it.

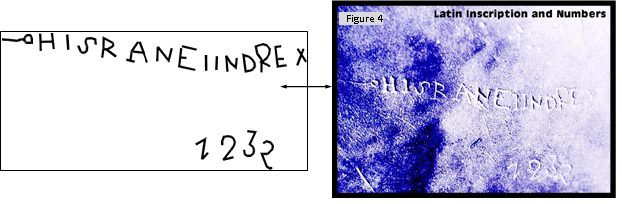

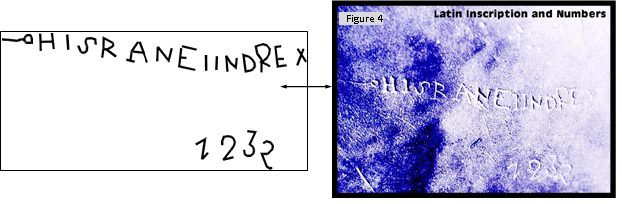

Figure 4: The Latin inscription, placed upon one side of the stone, reads as shown in the images above.

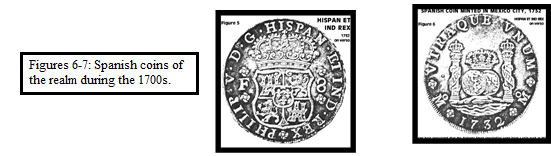

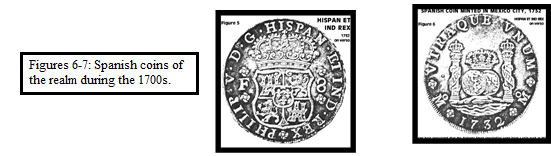

The translation of the letters in the inscription may involve coins minted in Mexico City (figures 6 and 7).

The speculation could go on indefinitely but the actual truth about the inscriptions may never be known. The archeology of the site, however, is a knowable factor. Towards these ends, the site (1Tu280) was revisited several times from 1976-80 by Caleb Curren and Keith Little. Thick secondary vegetation covered the site and little exposed ground surfaces existed, thus, the likelihood of productive surface collections was severely reduced.

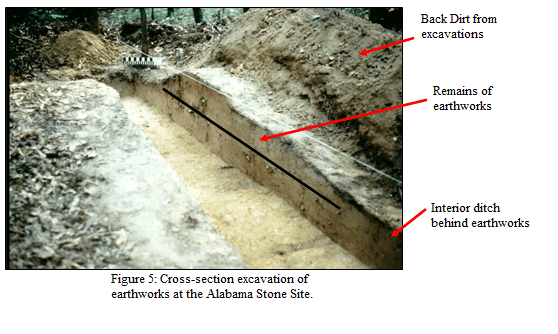

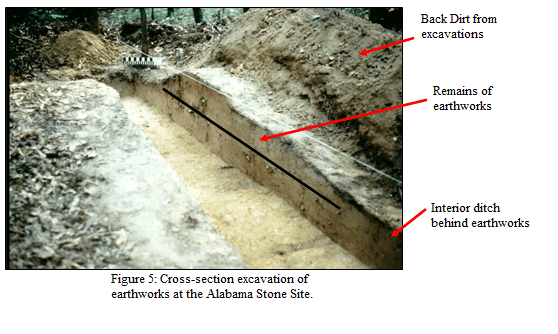

A low, linear rise and paralleling, shallow ditch was observed to traverse the peninsula from the riverbank to the creek bank (figure 2). The earthwork was not the 4-6 foot wall described in the nineteenth century for it was only about 40-50 centimeters (2-2½ ft.) in height. Many years of tree clearing, plowing, and erosion could easily account for the lower height of today. A hand dug excavation unit was cut through the earthwork to determine stratigraphy and artifact concentrations (figure 5). All dirt was screened through ¼” wire mesh and control was maintained horizontally and vertically by 1×1 meter squares dug in 15 centimeter levels. The length of the trench was 4 meters and the depth was 1 meter. No artifacts were found in the excavation but the profile revealed a mottled fill of the earthwork above the original ground surface. The slope of the ditch was also evident in profile, as was the original width of the earthwork, 2 meters.

More archeological investigations are needed for the Alabama Stone Site. There are many questions remaining to be answered. Is the earthwork historic or prehistoric? Is the Alabama Stone truly associated with the site or is it a hoax? If the earthwork is historic, why was it built and by which group? Was the ditch the end product or was the elevated earthwork the end product? If the site is prehistoric, is it related to other Woodland and Mississippian earthworks in the Southeast? Does the earthwork form the “fourth defense barrier” of a site on the elevated terrace of the peninsula, with the creek and river as the other three “barriers”? If the earthwork was built by the Spanish, why did they build it? Could the “2” in the “1232” inscription be a “7,” thus indicating a land claim by a Spanish expedition during the 1700s? For now, the site re- mains the “Mystery of the Alabama Stone,” as it has since the “worthy citizens” Tom Scales and his father found it atop the earthworks in 1817.

Europeans were prone to make land claims by carving symbols or statements into large stones. Might the Alabama Stone be such a land claim? The Spanish, with their newly found land and wealth in the Western Hemisphere, began to establish themselves quickly after the conquests in Peru and Mexico. A mint was established in Mexico City in 1536 by a royal decree. From this mint, went out coins of the realm with a statement of power and salutation molded upon them. With the newly gained territory the statement was appropriate: Hispan et Indiarum Rex, translated as, the King of Spain and the Indies. That is, the King rules Spain and the Western Hemisphere. The written inscription on the Alabama Stone might involve this phrase, whether taken from a coin or not.

The translation of the numbers of the inscription is more difficult. The first assumption is that they represent a date, presumably the date of the minting of the coin from which the inscription was copied. On the other hand, the numbers may not be a date at all but in fact, represent another matter entirely. What that matter might be is unknown at this time. The numbers do indeed appear to be “1232” but is that from a stone carver error or perhaps the representational numbers deviate from our 21st-Century understanding of symbology.

To summarize, the following scenarios are presented as possible explanations to the inscriptions in the stone. They are in no way meant to be the final word on the matter.

- The inscription is a hoax perpetrated by Tom Scales, his father or by someone else in the community to fool the townspeople or the Scales themselves. Judging by Pro- fessor Wyman’s statement of the character of Scales it seems unlikely that he would have done it. We have no way of knowing whether or not Tom Scales’ father or someone else in the community made the inscription. At least one author hints at such tomfoolery (Brannon 1925).

- The inscription was made by an Native aboriginal of the 17th, 18th, or 19th century who had in his possession a Spanish

- Europeans were present in west central Alabama in A.D.

-The inscription was made by a European who was present on the site in the 16th, 17th, or 18th century. The most likely century for this would have been the 17th or after due to the fact that the abbreviations as they appear on the Alabama Stone

inscription were not used at the mints until approximately the 18th century (Nesmith, 1955; Price 1980). Hypothesizing that the stone and earthworks date to the 1700s, an interesting scenario could be postulated. After years of struggle between the Spanish and French, the French left Pensacola Bay and the Spanish reoccupied the bay in 1723. Did the Spanish send land claiming expeditions into the interior of northwest Florida and southern Alabama during that period? Might one of these expeditions account for the Alabama Stone Site? Could a clue be that the French established Ft. Tombecbee in the general region of the Alabama Stone Site some four years (1736) after the possible date on the stone (1732)? The Alabama Stone Site is a conundrum wrapped in an enigma.

Bibliography

Brannon, Peter A.

1925 The Alabama Stone. Arrow Points: Monthly Bulletin of the Alabama Anthropological Society.

Montgomery, October 1925. Volume 11, Number Four. pages 47-49.

Clinton, Matthew

1958 Tuscaloosa, Alabama: Its early days, 1816-1865. The Zonta Club. Tuscaloosa.

Martin, Price

1980 Coins. The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited, London.

Maxwell, Thomas

1876 Tuskaloosa: the origin of its name, its history, etc. Tuscaloosa Gazette. Tuscaloosa.

Nesmith, Robert I.

1955 The Coinage of the First Mint of the Americas at Mexico City. 1536-1572. Quaterman Publications, Inc. Lawrence, Massachusetts.

Stanley, Will

1953 Were White Men Here in 1232? Birmingham News Monthly Magazine, Sunday, October 11, 1953, page 16.

- Article

-

On the eve of Alabama statehood in 1817, a large stone engraved with Latin inscriptions was found in the forest near Tuscaloosa. The stone evoked speculations then as it still does today. The first published report of the stone was in 1876 by Thomas Maxwell, a local Tuscaloosa landowner, who read his local history paper at a meeting of the Alabama Historical Society (Maxwell, 1876). A portion of the paper dealt with the Alabama Stone. Maxwell gives credit to professor Wyman of the University of Alabama for the original information concerning the stone. The following is the basic story as Wyman recorded it in his paper:

In 1817, Mr. Thomas Scales, a worthy citizen of the neighborhood, when a boy, removed with his father from North Alabama to the new settlement at Tuskaloosa falls. The first work they did was to clear a piece of ground. In clearing away the timber, they found an earthwork or embankment, in the nature of a fortification, which ran across the peninsula formed by the junction of the creek and the river (fig. 2). This embankment was about four feet high, and on the top of it, all the way across from river to creek, were growing the largest trees of the forest. At the foot of one of these (a large tulip tree, which stood on the very top of the embankment) they found a stone set up against the tree, with the lower end of the stone half buried in the soil. On the stone they discovered some curious letters, which being in Latin, they could not understand; and this, Mr. Scales said, induced his father to take the stone up to the settlement at the falls, now the town of Tuskaloosa, where it stood for a long time near to Squire Powell’s office, a subject of constant speculation for the curious. He remembered particularly (as he stood around it as a boy) to have heard the people say the inscription upon the stone was precisely the same as that upon the old Spanish dollar (Maxwell, 1876, pp. 79-80).

Figure 2: USGS topographic map of the Alabama Stone Site (1Tu280).

Possible defensive location?ll of this information was taken from Mr. Scales (then an old man) by Professor Wyman. Scales died not long after. According to Wyman, Tom Scales was well respected around the community and his story was taken as the truth. The stone was kept near the door of the log cabin which was the office of Levin Powell, Tuscaloosa County’s first tax collector, until 1824 when it was given to Silas Dinsmore of Mobile. Dinsmore was a trustee of the American Antiquarian Society of Massachusetts and, as such, sent the stone to Boston. It was catalogued as “The Alabama Stone” and displayed as one of the earliest evidences of European exploration in the New World (Clinton, 1958, pp. 11-12). In the 1950’s Alabama citizens began to object to the fact that the “Alabama Stone” was not in Alabama and “suggestions” were made that it be returned (Stanley, 1953). The stone was returned and is now housed in the Alabama Archives and History in Montgomery.

The stone is ferruginous sandstone and measures 21 1/2″ in length, 18″ in width, 12″ in breadth, and weighs about 200 pounds (figures 1 and 3). The general shape is “teardrop.” Over the surface of both sides of the stone are “gashes” and small conical holes. These configurations are seen frequently on stone found at aboriginal sites in the region. The “gashes” are assumed to have been made by Native peoples to use as edge sharpeners for ground stone tools. The conical holes are assumed to have been used as “holders” for (1) chert cobbles as they were flaked, (2) nuts as they were cracked, or (3) seeds as they were ground. The stone was probably used by Natives before and/or after the European inscription was carved upon it.

Figure 4: The Latin inscription, placed upon one side of the stone, reads as shown in the images above.

The translation of the letters in the inscription may involve coins minted in Mexico City (figures 6 and 7).The speculation could go on indefinitely but the actual truth about the inscriptions may never be known. The archeology of the site, however, is a knowable factor. Towards these ends, the site (1Tu280) was revisited several times from 1976-80 by Caleb Curren and Keith Little. Thick secondary vegetation covered the site and little exposed ground surfaces existed, thus, the likelihood of productive surface collections was severely reduced.

A low, linear rise and paralleling, shallow ditch was observed to traverse the peninsula from the riverbank to the creek bank (figure 2). The earthwork was not the 4-6 foot wall described in the nineteenth century for it was only about 40-50 centimeters (2-2½ ft.) in height. Many years of tree clearing, plowing, and erosion could easily account for the lower height of today. A hand dug excavation unit was cut through the earthwork to determine stratigraphy and artifact concentrations (figure 5). All dirt was screened through ¼” wire mesh and control was maintained horizontally and vertically by 1×1 meter squares dug in 15 centimeter levels. The length of the trench was 4 meters and the depth was 1 meter. No artifacts were found in the excavation but the profile revealed a mottled fill of the earthwork above the original ground surface. The slope of the ditch was also evident in profile, as was the original width of the earthwork, 2 meters.

More archeological investigations are needed for the Alabama Stone Site. There are many questions remaining to be answered. Is the earthwork historic or prehistoric? Is the Alabama Stone truly associated with the site or is it a hoax? If the earthwork is historic, why was it built and by which group? Was the ditch the end product or was the elevated earthwork the end product? If the site is prehistoric, is it related to other Woodland and Mississippian earthworks in the Southeast? Does the earthwork form the “fourth defense barrier” of a site on the elevated terrace of the peninsula, with the creek and river as the other three “barriers”? If the earthwork was built by the Spanish, why did they build it? Could the “2” in the “1232” inscription be a “7,” thus indicating a land claim by a Spanish expedition during the 1700s? For now, the site re- mains the “Mystery of the Alabama Stone,” as it has since the “worthy citizens” Tom Scales and his father found it atop the earthworks in 1817.

Europeans were prone to make land claims by carving symbols or statements into large stones. Might the Alabama Stone be such a land claim? The Spanish, with their newly found land and wealth in the Western Hemisphere, began to establish themselves quickly after the conquests in Peru and Mexico. A mint was established in Mexico City in 1536 by a royal decree. From this mint, went out coins of the realm with a statement of power and salutation molded upon them. With the newly gained territory the statement was appropriate: Hispan et Indiarum Rex, translated as, the King of Spain and the Indies. That is, the King rules Spain and the Western Hemisphere. The written inscription on the Alabama Stone might involve this phrase, whether taken from a coin or not.

The translation of the numbers of the inscription is more difficult. The first assumption is that they represent a date, presumably the date of the minting of the coin from which the inscription was copied. On the other hand, the numbers may not be a date at all but in fact, represent another matter entirely. What that matter might be is unknown at this time. The numbers do indeed appear to be “1232” but is that from a stone carver error or perhaps the representational numbers deviate from our 21st-Century understanding of symbology.

To summarize, the following scenarios are presented as possible explanations to the inscriptions in the stone. They are in no way meant to be the final word on the matter.

- The inscription is a hoax perpetrated by Tom Scales, his father or by someone else in the community to fool the townspeople or the Scales themselves. Judging by Pro- fessor Wyman’s statement of the character of Scales it seems unlikely that he would have done it. We have no way of knowing whether or not Tom Scales’ father or someone else in the community made the inscription. At least one author hints at such tomfoolery (Brannon 1925).

- The inscription was made by an Native aboriginal of the 17th, 18th, or 19th century who had in his possession a Spanish

- Europeans were present in west central Alabama in A.D.

-The inscription was made by a European who was present on the site in the 16th, 17th, or 18th century. The most likely century for this would have been the 17th or after due to the fact that the abbreviations as they appear on the Alabama Stone

inscription were not used at the mints until approximately the 18th century (Nesmith, 1955; Price 1980). Hypothesizing that the stone and earthworks date to the 1700s, an interesting scenario could be postulated. After years of struggle between the Spanish and French, the French left Pensacola Bay and the Spanish reoccupied the bay in 1723. Did the Spanish send land claiming expeditions into the interior of northwest Florida and southern Alabama during that period? Might one of these expeditions account for the Alabama Stone Site? Could a clue be that the French established Ft. Tombecbee in the general region of the Alabama Stone Site some four years (1736) after the possible date on the stone (1732)? The Alabama Stone Site is a conundrum wrapped in an enigma.

- Bibliography

-

Bibliography

Brannon, Peter A.

1925 The Alabama Stone. Arrow Points: Monthly Bulletin of the Alabama Anthropological Society.

Montgomery, October 1925. Volume 11, Number Four. pages 47-49.

Clinton, Matthew

1958 Tuscaloosa, Alabama: Its early days, 1816-1865. The Zonta Club. Tuscaloosa.

Martin, Price

1980 Coins. The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited, London.

Maxwell, Thomas

1876 Tuskaloosa: the origin of its name, its history, etc. Tuscaloosa Gazette. Tuscaloosa.

Nesmith, Robert I.

1955 The Coinage of the First Mint of the Americas at Mexico City. 1536-1572. Quaterman Publications, Inc. Lawrence, Massachusetts.

Stanley, Will

1953 Were White Men Here in 1232? Birmingham News Monthly Magazine, Sunday, October 11, 1953, page 16.

- Download PDF Version