Ham Bones: Marker Artifacts for the 1559 Luna Expedition Settlement at Pensacola Bay (And, Why Were No Live Pigs Ever Sent?)

by David B. Dodson

Contact Archeology Inc.

March 2018

Abstract

The Spanish financial documents related to the 1559 Luna Expedition delineate the amounts of various foodstuff shipped and the amounts paid the vendors and mule drovers for their deliveries to the Gulf port at Vera Cruz. While live pigs were a vital if not a “last resort” food source for the Soto expedition 20 years earlier, curiously the Luna records reveal that apparently no live pigs were ever sent to la Florida during that expedition—only cured or salted pork products, mainly slabs of bacon and hams.

This article will discuss the prospects of pig bones from the hams as marker artifacts for the Luna Expedition and investigate why no live pigs were ever sent to the Luna colonists in la Florida.

Salt Pork on the Luna Expedition: The Evidence

In analyzing the Spanish financial records concerning outfitting the Luna Expedition, it appears that the pork products provided for the initial sail (called the armada) to la Florida weighed over 21,000 pounds, or 10½ tons. Entries indicate that these pork products were mainly slabs of bacon (Figure 1) and hindquarters (Figure 2), which I like to call “hams” for its simplicity.

Figure 1. Slab of cured bacon, and a “slice” to the side.

Figure 2. Cured “hams” hanging in a butcher shop in Spain.

(The longer the cure, the more the cost—just like good, aged red wine.)

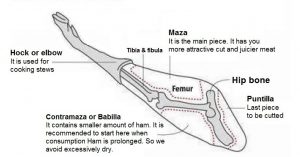

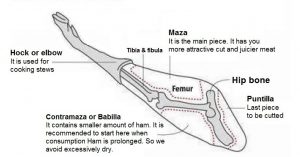

Typically, slabs of bacon have no bones, whereas the hams would have four main bones—part of the pelvis, the femur, and the tibia and fibula (Figure 3).

Figure 3. View of a Spanish ham showing the meat cuts as well as the four main

bones—the hip bone, the femur with its large distinctive ball ends, and the

thinner tibia and fibia.

(Of course, there are smaller bones associated with the hindquarters of a pig—including the hoof itself, but for the succinctness of this discussion, the small ones will not be included in this pig bone discussion—just the big ones.)

The financial records do not discern how many hams were sent versus slabs of bacon, so we cannot definitively ascertain the number of hams shipped. But knowing the Spanish demand for pork, and salt assuring a lack of spoilage and safeness from parasites; ease of cutting and weighing out rations, and versatility of hams in preparing meals, one could hypothesize that the large legs of meat (hams) made up at least one half of the total amount of salt pork.

With that mean—and each ham typically weighing an average of 30 pounds —that would approximate to at least 300 hams containing 1,200 large bones. A critic could argue that since not all the food was unloaded off the ships upon arrival at Santa Maria de Ochuse (Pensacola Bay) in August of 1559 that not all the pork products made it ashore. But with half the pork ashore, that would still be approximately 150 hams unloaded with the associated 600 bones.

On the subsequent four resupply shipments to the Luna expedition, over 30,500 pounds, or 15 tons, of salt pork products were also shipped. One could again hypothesize that half were hams, which would then equate to 500 hams with 2,000 bones. Therefore, with the possibility of the total amount of these 4 distinct possible pig bones numbering in the thousands, they could serve as marker artifacts for the location of the Luna settlement site at Santa Maria de Ochuse. Indeed, the very thick, or stout, femur—measuring about 12 inches in length with distinctive ball ends—would definitely be hard to overlook or be misidentified (Figure 4).

Figure 4. A stout femur of a pig

with its distinctive ball ends.

Conversely, the long searched for Soto battle site known as Mabila on the Alabama River near the interior Luna settlement site of Santa Cruz de Nanipacana (October 1559-June 1561) would be indicated by the presence of many more different types of pig bones, especially the skulls, jawbones, and teeth from the once live pigs they slaughtered to augment their dietary needs.

Faunal remains and human remains have been found in archeological sites in northwest Florida and south Alabama dating back hundreds and even thousands of years ago. The remains were found in a variety of soil types, therefore, the prospect of unearthing the marker ham bones dating to only some 450 years is very probable.

Also, even if the Luna colonists boiled the pig bones to make a broth or fractured the leg bones for marrow extraction, the dense bones of the pigs’ femurs and hips would survive. Zooarcheologists are capable of identifying such bones as Old World ungulates (hoofed mammals).

Further—and very importantly—the salt pork served as a “ready-made” dietary supplement of salt (NaCl, sodium chloride), which is needed for all humans and other animals to survive, much less keep hydrated and endure the very hot and humid climate of la Florida. Conversely, the slaughtering of live pigs might provide the needed proteins for the colonists, but very little if any salt. Thus, casks of salt were always being sought and sent to the Luna Expedition by the viceroy—not just for seasoning foodstuff—but for the health of the expedition.

The importance of salt in la Florida is made paramount by a quote from the Soto Expedition:

There was much want of salt, also, that sometimes, in many places, a

sick man having nothing for his nourishment, and wasting away to

bone, of some ail that elsewhere might have found a remedy, when

sinking under pure debility he would say, “Now, if I had but a slice of

meat, or only a few lumps of salt, I should not thus die.”

Similarly, Luna Expedition participant Fray Domingo de la Anunciación wrote on August 1, 1560, from the chiefdom of Coosa in today’s northern Alabama:

…we people of this camp now find ourselves in extreme need of shoes—which we

are now all without—and of salt, [chili] peppers, horseshoes, and other things

without which one passes this life badly.

Therefore, the importance of salt on the Luna Expedition will be explored and discussed in a future article; and there is little doubt that salt pork served many purposes towards the health of the colonists as well as the health of the expedition.

Examples of the Spanish Financial Documents

One example of a financial entry in the Spanish records, which concerns the outfitting of the initial armada of June 1559 with pork products, reads as follows:

Miguel Carrasco, drover, was paid 18 pesos 6 tomines of the said common gold that he was owed for the delivery of 60 portions of salt pork that he brought in 6½ loads that his servant, Pero Hernandez, delivered in the said port of San Jhoan de Ulua at an amount of 2½ pesos per load as it appears by warrant of the said Alcalde Mayor dated on the said day [of May 18, 1559] and his letter of payment before the notary (Childers 1999).

Some of the entries concerning the first through third resupply shipments to Santa Maria de Ochuse read as follows:

Item: The said Pedro de Yebra presented Item: The said Pedro de Yebra presented the account for 58 pesos 2 tomines of common gold that he gave and paid to Alonso de Ledesma, drover, for the contract for the transport of 198 portions of salt pork from Mexico City to the port of San Juan de Ulua which weighted 233 arrobas for the aid sent to the governor and soldiers that were in Florida in His Majesty’s ships, at a cost of 2½ pesos for each load as it appears by warrant of the said Bachiller Martinez dated 29 January 1560 ….(Childers 1999).

Item: The said Pedro de Yebra presented the account for 22 pesos 6 tomines of common gold that he gave and paid to Juan de Mesa, drover, for the contract for the transport of 54 arrobas of portions of salt pork and 55 arrobas of hams 55 arrobas of coarse cotton shirting and six bundles of serge a leather covered chest of thread and 2 barrels of gunpowder and 29 axes that he carried from Mexico City to the port of Veracruz for the aid sent to the governor and soldiers that were in Florida as it appears by warrant of the said Bachiller Martinez dated 7 February 1560…(Childers 1999).

Item: The said Pedro de Yebra presented the account for 169 pesos of common gold that he gave and paid to Hernan Ponçe, drover, for the contract for the transport of 293 portions of salt pork, six leather covered chests and six chests that weighed 338 arrobas which he carried to the city of Veracruz for the second aid sent to the governor and soldiers that were in Florida at 4 pesos per load of 8 arrobas as it appears by the warrant of the said Bachiller Martinez dated 9 May 1560….(Childers 1999).

Item: The said Pedro de Yebra presented the account for 22 pesos 6 tomines of common gold that he gave and paid to Juan de Mesa, drover, for the contract for the transport of 54 arrobas of portions of salt pork and 55 arrobas of hams… 55 arrobas of coarse cotton shirting and six bundles of serge, a leather covered chest of thread and 2 barrels of gunpowder and 29 axes that he carried from Mexico City to the port of Veracruz for the aid sent to the governor and soldiers that were in Florida as it appears by warrant of the said Bachiller Martinez dated 7 February 1560…(Childers 1999).

Item: The said Pedro de Yebra presented the account for 169 pesos of common gold that he gave and paid to Hernan Ponçe, drover, for the contract for the transport of 293 portions of salt pork, six leather covered chests and six chests that weighed 338 arrobas which he carried to the city of Veracruz for the second aid sent to the governor and soldiers that were in Florida at 4 pesos per load of 8 arrobas as it appears by the warrant of the said Bachiller Martinez dated 9 May 1560….(Childers 1999).

And another concerning the fourth and last resupply in early April 1561 personally delivered to Santa Maria de Ochuse by the new governor—Ángel de Villafañe—reads:

Item: The said Pedro de Yebra presented the account for 92 pesos 4 tomines of common gold that he gave and paid to Diego Gutierrez, drover, for the contract for the transport of 200 portions of salt pork that weighed 252 ½ arrobas that he carried from Mexico City to Veracruz at an amount of 3 pesos per load, which was for the fourth aid that was sent to the said governor and soldiers that were in Florida and he had 2 pesos subtracted from the total because he was short 2 hams on delivery and the 92 pesos 4 tomines were what remained as it appears by certification of the said Juan Valiente and warrant of the said deputy officials dated 3 March 1561…(Childers 1999).

The latter entry indicates that the words “salt pork” and “ham” could be interchangeable, with “salt pork” perhaps the inclusive and generic term chosen by the accountant to minimize numerous micro-entries. Remember, the accountant is using a quill pen dipped in an ink bottle to write! Also, the financial record is not really about the product or service being rendered, but the MONEY and how was it spent appropriately. Therefore, the financial records pertaining to the Luna Expedition were actually an audit of how the King’s money was spent eight years after the fact! As one modern historian noted, “the Spanish Imperial administration almost never forgot anything, but it often took a long time to remember.”

The Soto Expedition and Live Pigs

Soto arrived to la Florida in May of 1539 with thirteen sows or producing female pig as a food source. He had procured the pigs in Cuba where there was an abundance of wild cows and hogs as well as domesticated herds (Figures 4, 5, and 6). It is said that Queen Isabella insisted that Columbus take eight pigs with him on his second voyage, which landed both him and the pigs in Cuba. There, the pigs quickly multiplied and eventually became a readily available and inexpensive food source for the inhabitants. Even today, pigs are a considerable part of Cuban cuisine.

Figure 5. Cuban sow with piglet.

Figure 6. Cuban sow with piglets trailing.

By the following March-April of 1540 when the Soto expedition had journeyed beyond Apalachee and Patofa and into the interior of today’s Georgia, the herd of pigs had multiplied to over three hundred (Elvas 1968). Domestic pigs have a gestation period of around 121 days, and deliver around 8 piglets to a litter. A modern sow can have 1.5 liters per year, and it is possible to have a young female pig or gilt begin reproducing at 6 months. Thus, it was entirely possible to achieve the number mentioned in the records of the expedition.

When the supply of maize was used up or unavailable, Soto would order the systematic slaughtering of the pigs, allocating daily only a half pound of meat for each soldier. Another account of the slaughter relates that a pound of pork was allocated (Elvas 1968). Apparently, during this time of hunger around the Indian chiefdoms of Ocuti and Cafaqui in the Province of Altapaha, a great number of the swine were slaughtered. Interestingly, there are later accounts of hunger soon thereafter with the men eating turkeys and dogs for a meat, which were provided by the Natives (Elvas 1968)—not Soto’s pigs! Thus, one can see that Soto only employed his pigs for food when no other source was obtainable. And calculating that six hundred famished soldiers—given a ration allocation of one pound a day—could consume three to four 250-pound butchered pigs every day.

Logistically, herding swine is not that difficult. Pigs can swim and it is possible to have a sow lead her piglets across a river much like a mother duck. Likewise, with a good swineherd, Soto was able to herd his pigs all the way from mid-Florida, up through Georgia and the Carolinas, down through Tennessee and Alabama, and finally across Mississippi.

One of the last mentions of swine on the entrada is after the battle of Mauvila when Soto and his men had set up winter camp at the deserted Indian village of Chicaza in today’s northern Alabama. Eventually, in March of 1541, the Indians attacked the Spaniards within the fortified village and put it to fire. The fire was so fast and encompassing that men, women, and numerous horses were consumed (Garcilaso de la Vega 1951). The Fidalgo de Elvas recorded the following concerning the swine:

The town lay in cinders…There died in this affair eleven Christians, and fifty horses. One hundred of the swine remained, four hundred having been destroyed, from the conflagration of Mauvilla (Elvas 1968).

Garcilaso de la Vega, The Inca, presents another account concerning the remaining swine:

But since the fire on the night of the battle was so sweeping, it seized the swine also, and none of them escaped except the suckling who were able to slip between the palings of the fence, Now those animals were so fat with the great amount of food they had found in that place that the lard from them ran for a distance of more than two hundred feet, and this loss was lamented no less than that of men and horses because the Castilians suffered from a lack of meat and were saving the swine for the comfort of the sick (Garcilaso de la Vega 1951).

Thus, one can see that the pigs Soto brought had been healthy, productive, had great endurance, and importantly, possessed the instinct to survive. And since pigs can survive by literally rooting out plant parts, grubs, small rodents, etc., found in the wild, they were proven to be extremely prolific in expanding their population.

Knowing that twenty years earlier, the live pigs that Hernando de Soto brought along on his expedition to the American Southeast were very instrumental in keeping the expedition from starving, one questions why Viceroy Luis Velasco did not include swine in the planning and implementation of the initial Luna armada, much less in the subsequent aids to help sustain the Luna expedition.

The communications of the viceroy with Luna clearly indicate he was very familiar with the Soto expedition, and there were eight Soto survivor soldiers mandated by the viceroy to go on the Luna Expedition. They, too, would have been very familiar with the value of live pigs on a land expedition. Therefore, one could conclude that having pigs somewhat corralled at Santa Maria de Ochuse (Pensacola) or up at Nanipacana would have been a fruitful endeavor for the settlers on the Luna expedition—but it never happened.

On the other hand, it appears by the records that any live animal sent with or to Luna in la Florida were never realistically considered for husbandry, but quickly slaughtered and consumed by the famished population. This included sheep, goats, and cattle. In spite of this, the viceroy finally wrote to Luna on September 15, 1560, informing the governor that he intended to send the following:

In the month of January this bark or the galleon San Juan will set sail, carrying one thousand fanegas (or bushels) of corn and dried beef, a few live hogs, and such added supplies as are necessary, so that you and the people who are at the port may be maintained until you learn where the people are who went inland, and whether they have found a place where they can be maintained and fed (Priestley 1928).

However, the present records inform that such a large amount of food—much less live hogs—was never actually sent (Childers 1999, Padilla 1596, Priestley 1928). Consequently, the couple of hundred remaining soldiers and servants remaining at Santa Maria de Ochuse with Luna after much of the colonists and sick had been evacuated, again suffered great hunger from October of 1560 until the new governor Ángel de Villafañe arrived with supplies during the first week of April 1561 (Padilla 1596, Priestley 1928).

Also, the connection of finding various pig bones and designated them “marker artifacts” for a 16th-Century Spanish site demands caution as we have learned from previous interpretive errors. Indeed, in 1987 reputable archeologists excavating an early Spanish site in Tallahassee, Florida, found a pig jawbone amongst 16th-Century Spanish artifacts. The pig bone was energetically considered “positive evidence” of a Soto site. However, many years later when testing was eventually done, the pig bone turned out to be ca. 1850—over 400 years after the Soto expedition. But unfortunately, the error had already become an accepted “fact” and included in modern Soto histories and on historical plaques, further muddying the search for the allusive Soto Trail throughout the Southeast. We do not need to make the same mistake on the search for the Luna Colony.

Other Spanish Expeditions with Pigs or Only Salt Pork

Narváez in la Florida

It should also be noted that the Panfilo Narváez expedition to la Florida in 1528—according to Cabeza de Vaca—initially only had a diet of hard bread with salted pork before maize could be found and obtained from the Native population. The expedition, apparently, carried no live pigs. Cabeza recorded:

Saturday, the first of May…[Governor Narváez] commanded that each one of those who was to go with him be given two pounds of hardtack and a half a pound of salt pork. And thus we set out to enter the land.

Coronado in the American Southwest

In 1540 Francisco Vázquez de Coronado led an expedition up the western side of New Spain (Mexico) into today’s American southwest searching for gold and other riches, which were purported to be found within the fabled Seven Cities of Cibola.

Luna was a primary captain and also served as one of the maestre de campos, or head of the main camp. This position required leadership and knowledge of logistics because it involved “moving” the main force forward to support Coronado and his horse-mounted reconnaissance or advanced guard force. The advanced guard would venture many days if not weeks ahead. The maestre de campos was also in charge of food management and rations, and oversaw the herds of live animals brought along to feed the Spanish soldiers and thousands of Native soldiers who also went on the expedition. While not a “warrior” position per se, it was an esteemed and responsible position. Luna’s success serving Coronado—as well as his wealth obtained marrying a wealthy widow of two First Conquerors of Mexico—was one of the reasons Viceroy Luis de Velasco chose Luna for the la Florida expedition.

When the Coronado expedition first left the environs of Mexico City in 1540, the food herds of cattle, sheep, and hogs numbered in the thousands. Participant Melchor Pérez testified later that he had taken 1,000 hogs and sheep valued at around 1,200 pesos (Flint 2003). However, by the time the expedition had ventured beyond the relative comfortable temperature of the plateau of central Mexico and into the arid and sunbaked grasslands and deserts of today’s Arizona and New Mexico, it appears that only the grazing animals—cattle and sheep—remained for food stock. The cattle tallied around 500 and sheep around 5,000 (Flint 2003). The bones from these non-native animals have served archeologists to identify several Coronado sites (Vierra 1997).

Why No Live Pigs with Luna?

The question of “why no live pigs were ever sent with or to Luna in la Florida” still begs an answer. Was the micro-manager Viceroy Velasco remiss in choosing the appropriate “food supply,” or were there other factors? As stated before, his letters written to Governor Luna during the expedition indicate—without doubt—that the viceroy was very familiar with all aspects of the Soto expedition and the ever growing swine herd Soto took along. The answer may lie in many possibilities. Presented below are some that will be considered, as well as an unusual one that speaks to the “jinxed” nature of la Florida and the expedition itself.

- Realism

- Practicality

- Availability

- Logistics of rations

- Salt for the health and survival of the expedition

- Superstition

1) Realism:

Any live food animals brought on the initial armada or sail to Santa Maria de Ochuse appear not to have completed the voyage. It is most probable that any feed set aside for such animals for a 15-day voyage likely ran out during the 45-day extended sail, or got sick and died, or were consumed by the peoples on board the ships. Any live food animals sent on the subsequent resupplies to Santa Maria de Ochuse for the starving and dying peoples of the Luna Expedition would not have lasted a day upon arrival, especially after the devastating hurricane; such food sources would have been roasting over a fiery pit before the evening! Eleven calves sent on the first resupply to Santa Maria de Ochuse around November 1559 appear never to have been allowed to mature. And by the time the expedition was located up at Nanipacana, even posting guards would have been futile inasmuch as the disobedient soldiers would have rather been hung and experienced a quick death for their thievery than to continue to suffer a slow death via starvation. While we presently do not have the original letters Luna wrote to Viceroy Velasco, it is probable that Luna informed the viceroy that salted pork and hams would be more appropriate to be sent over live animals as the rations could be better kept under lock and key, appropriately weighed, and allocated to the peoples. Also, while hogs can practically survive on anything they can put in their mouths there was no food—not even wild vegetation within miles—that the hogs could live upon and multiply. The Native population had scorched and laid bare the surrounding lands of everything edible that even the horses had no grasses to graze upon and could barely support a mount.

Also, it should be noted that the swine brought on the Soto Expedition survived “illegal slaughtering” even during periods of severe hunger by the soldiers because Governor Soto owned the swine. Only he could allocate or order the killing of his herd; and it is likely Soto would have slowly tortured and killed or set the war dogs on anyone that stole his personal possessions. Indeed, in March of 1540—during a trek through an unpopulated area without a Native population—to obtain foodstuffs, Soto finally ordered some of his own swine killed to appease the great hunger of his men.

2) Practicality:

This factor is somewhat based on the 1st, but also addresses the nature and “occupations” of the soldiers and colonists on the expedition.

Basically, although the expedition had brought along and unloaded tools for farming, the peoples and soldiers were not from farming backgrounds, much less experienced in animal husbandry. Farming in la Florida—as was experienced in Mexico—was mainly to be relegated as the tasks of the Native populations, once they had been subjugated. Having haciendas and owning herds of cattle and other grazing stock were the dreams of the colonists, and that is why they had sought their fortune on the expedition. Most of the colonists had nothing to lose by venturing to la Florida, having left anything behind in Mexico; otherwise they would have never sought opportunity and a life elsewhere! Viceroy Velasco recognized this fact, and wrote Luna that experienced farmers could eventually be solicited from Spain.

3) Availability:

While the Spanish had introduced cattle, goats, sheep, and pigs to New Spain after the Conquest of 1521, the wide acceptance of these foodstuffs at the time of the 1559 Luna Expedition by the Native population was still minimal. Animal husbandry was more domestic in character and relegated to the hands of the Native women around their households, rather than being a distinct male profession—raising such animals in great numbers as a business. However, the introduction of herds of cattle in the valleys around Oaxaca by the Spanish became so destructive to the native crops of that fertile valley that cattle were outlawed by the viceroys. This destruction problem was also similar with the introduction of pigs and sheep herds. Therefore, (besides fish) the traditional and transitional native diet for meat was satisfied through the limited raising of ducks and geese, pigs and goats, rabbits, native dogs, and even coyotes. Thus, to satisfy the pork needs of the non-farming Spanish population in Mexico City, Spanish entrepreneurs developed large pig farms located near the main roads and close to the city. This included Apam (northeast at 88 kilometers), Calpulalpan (east-northeast at 72 kilometers), and Toluca (west-southwest at 68 kilometers).

Utilizing the main connecting roads, herding or even carting the pigs to market in Mexico City would only require a couple of days, and one of the main places where salt was obtained to cure the pork was located in the southern lake area upon which Mexico City was situated. Thus, the area in and around Mexico City was more of the central area for large swine production and processing—not along the coastal areas near the port of Vera Cruz. Therefore, hauling vast amounts of salt pork on the backs of mules from Mexico City to Vera Cruz was the preferred option to supply the Luna Expedition.

Also, the period records show that the meals provided by the Native women for the overland trek of the expedition on the road from Mexico City to the departure point at Vera Cruz only included tortillas comprised of hens, eggs, maize, frijoles, chili peppers, and fish—but no pork products; and only the labor to make the meals was considered an expenditure by the Spanish. The contribution of foodstuffs was part of the old tributes previously imposed by the Aztec rulers and continued by the Spanish. Conversely, the newly imported Old World pigs were not part of the old tribute and therefore any pigs the Natives might have been raising within their small compounds were not offered up in tribute. Pork products would have to be purchased by the Crown.

4) Logistics of Rations:

When cutting a freshly roasted pig it is harder to allocate and weigh for procuring ration portions as the moisture content varies, and it also involves who gets warm meat and who near the “end of the line” gets the cold meat. This problem could affect the morale of the soldiers—not among the officers and Royal Officials who would surely have gotten hot portions—but among the common soldiers and colonists. The servants, forced laborers, and the Aztecs along on the expedition would probably have been just glad to receive any foods—hot or cold! And even if you had many roasting pits cooking at the same time, feeding over 1,500 persons was still a logistic nightmare.

However, in salted pork—bacon or ham—the meat is very consistent and all “cold” portions could be allocated at an equal and fair weight. Thus, it would be left to each individual or groups to warm or cook their meats at their own discretion and ability to prepare a cooking fire. This would of course also depend upon the ability of the serving people and women and children to collect the appropriate firewood needed to prepare a hot meal.

5) Health and survival of the expedition:

Most of the Spanish soldiers and colonists on the Luna Expedition heralded from the central, high plateau regions of New Spain where the comfortable, mild temperatures afforded a fairly healthy climate year round, even during the summer months. Therefore, it was possible to perform heavy labor without an excess of sweat that the humid hot seasons in la Florida wrought. The salt in the salt pork products found around Mexico City could have supplied most of that necessary nutrient without much supplement.

However, knowledge from the Soto survivors of the known climates of la Florida required that the Luna Expedition take along casks and leather baskets of salt to augment the dietary requirements.

The financial entries mention the sending over 100 fenegas (Spanish bushels) of salt for the initial armada in June 1559. However, by the time the Viceroy Velasco discusses in October of sending the first resupply ships after the devastating hurricane and two months of intense summer heat, he writes that he will also have a bark built at the coastal city of Panuco—north of Vera Cruz and a “safer coastal sail” to Pensacola Bay—whereby to take salt, live cattle, and other needed provisions.

While the subsequent resupply shipments also record the sending of more salt, one must also consider that perhaps the salt pork (and some barrels of salt meats) were also designed to provide the peoples with a “built in” salt allotment within their food sources. That is something live pigs could not achieve.

6) Superstition:

Atlantic seamen in the West Indies (at least as recorded by the 1600s) had a bizarre superstition related to swine. Pigs themselves were held at great respect because they possessed cloven hooves just like the “devil” and the pig was the signature animal for the Great Earth Goddess, who controlled the winds. As a result, these fishermen never spoke the word “pig” out loud, instead referring to the animal by such safe nicknames as Curly-Tail and Turf-Rooter. It was believed that mentioning the word “pig” would result in strong winds. Actually killing a pig on board the ship would result in a full scale storm.

This becomes relevant to the Luna Expedition in that mariners were afraid to sail to Pensacola Bay because of the reputation of la Florida and its distant ports plagued by hurricanes and “murderous” Native populations who would kill any survivors of shipwrecks. The shipwrecks and ultimate deaths of survivors of the treasure fleets of 1545, 1553, and 1554 on the coasts of “la Florida” were clearly still on the minds of the peoples in New Spain. Further, the deaths of prominent Dominican fray Luis Cancer and his companions on their missionary expedition to the coast of la Florida in 1549 made the possible peaceful interaction amongst the Natives a very questionable enterprise. Indeed, the outfitting of the first reconnaissance expedition, led by Guido de la Bazares to rediscover Ochuse in 1558 in preparation for the Luna Expedition the following year, included much personal armament for the soldiers that were to go along as well as harquebuses and a variety of light and heavy cannons for protection.

Thus, word of the devastating hurricane upon the Luna fleet in September 1559 brought much distress in New Spain because of the belief that the expedition was perhaps doomed from the start by the hand of God.

“…If you had not gone out toward the open sea as you did, you would have reached it [Pensacola Bay] some days sooner; if the pilots had been able to do so they would have saved time and labor and the loss of some of the horses, and possibly the loss of the ships. But since our Lord ordained it thus there is nothing to be said except to give Him many thanks, and pray to Him that in what remains for you to do. He will guide, enlighten, and assist you…I trust in the Lord that He will give you your reward for them in this life and the next.”

Indeed, the hurricane “was sent upon the expedition” on a Sunday—the Holy Sabbath! The thought or idea that God would allow such destruction on “His Day” would have had many contemplating and asking, “What had they done to deserve this punishment?” Was it their gluttony while on the ships? Religious historian Dávila Padilla noted in his 16th-Century narrative that, “there was enough food in the ships for over a year, even though it was being excessively eaten by the 1500 persons that were there.” And had not everyone been properly dedicated with the zeal as they should have been and were more concerned with their own comforts and well-being than the mission at hand, which included the conversion and saving of many Native souls? Again, Dávila Padilla writes of the arrival of the expedition to the shores of Pensacola Bay and mentions what might be considered an “initial weakness” before tackling the job at hand:

When the new settlers saw themselves in such a peaceful place, for some days they enjoyed the freshness of the place and the gift of the tide. Some sat down on the sand before the Sun could heat them and others when the evenings after the sunset, made them cool, exercised the horses, showing off their finery and dexterity: others went in the barks and coasted the shore. Others considered it from the land, regaling themselves with the view of the meek waves, which as they were peaceful and gentle, arrived calmly to the shore and without going astray, they returned to the sea. They arrived as if to greet those on the land, retreating from them without disturbing anything. Finally,{those that had gone in the barks, and} those that crewed them all rejoiced together because it is not only an entertaining thing to go together to the sea but also to sail close to land. But as the voyage had not been to look for recreational activities nor to hold fiestas, then true things were discussed, and an order given to enter and explore the land, and to give his Majesty an advisory on what had happened in compliance with his royal cédula.

Compounding all of this, the mariners that could be found in New Spain were afraid Governor Luna at Santa Maria de Ochuse would “impress” the seamen in service on the land, as he had done with common mariners who survived the hurricane, but lost their ships in the waters of Pensacola Bay. As a result, Viceroy Velasco specifically instructed Luna that “all [the mariners] who go [on the resupply ships] may freely return, and some of those that were saved from the ships that were lost and who have wives in Spain you will send back in order that they may collect the wages which are due them and go home from here.”

There can be little doubt that the recruitment of scarce seamen in New Spain to man the resupply ships destined for the Luna Expedition—full of food provisions for the starving soldiers and settlers—was a factor in the many delays that always seemed to plague the la Florida expedition. Indeed, the record is replete with others hiding from the commands of the viceroy—and therefore the will of their King—especially to avoid a trip to la Florida.

Conclusion

The unearthing of a substantial quantity of “ham bones”—along with Mexican-style metates and Christian burials as discussed in previous articles (Dodson 2016, 2017) in concert with other features—such as numerous fire hearths, refuse pits, and remnants of structures—would all indicate if not verify a Luna settlement site in Pensacola (Curren 2017). Otherwise, finding 16th-Century Spanish artifacts mixed with Native artifacts only indicates Native contact with one or more Spanish entradas during the 16th Century. This could include early contact and trade by Native populations with the 1528 Narvaez Expedition or the 1540 Soto Expedition or the Luna Expedition or interaction with Spanish slavers or a combination of all of the above.

Also, the question of why no live pigs were ever sent to the Luna colonists in la Florida is still not fully answered. More research into the Spanish records must be initiated to discern a more definitive answer.

For now, it appears that the soldiers and colonists on the Luna Expedition did not enjoy “a grand pig roast” of freshly butchered swine, only meals of salted pork in “sandwiches,” which manifested themselves as one of the ingredients in their tortilla rations. As such, what remaining leg bones from the tons of salted pork sent to Pensacola Bay should serve as additional marker artifacts to indicate the Luna settlement site of Santa Maria de Ochuse at today’s Pensacola Bay; and to a lesser extent, the site of the Luna settlement at Santa Cruz de Nanipacana on the lower Alabama River.

Sources

Peter Bakewell, in collaboration with Jacqueline Hollar, A History of Latin America to 1825, 3rd Edition, Wiley-Blackwell, United Kingdom, 2010.

Fletcher S. Bassett, Legends and Superstitions of the Sea and Sailors, Singing Tree Press, Detroit, 1971, facsimile of 1885 edition.

Pedro de Castañeda de Nájera, ed. John Miller Morris, Narrative of the Coronado Expedition, R.R. Donnelley & Sons Company, Chicago, 2002.

Wayne Childers, Translation, AGI. Contaduria 877, 1999.

David B. Dodson, unpublished manuscript concerning new documents, translations, and corrected aspects of the present narrative of the Luna Expedition, 2002-till present.

David B. Dodson, Mexican Metates in the 16th Century Southeast: Marker Artifacts for the 1559 Luna Settlements? December 2016,

http://archeologyink.com/mexican-metates-in-the-16th-century-southeast-marker-artifacts-for-the-1559-luna-settlements/

Fidalgo de Elvas, True Relations, as found in Narratives of De Soto in the Conquest of Florida, Translated by Buckingham Smith, Palmetto Books, Gainesville, Florida, 1968,

Shirley Cushing Flint, The Financing and Provisioning of the Coronado Expedition, 51, Chapter 3 of Richard Flint and Shirley Cushing Flint, eds. The Coronado Expedition From The Distance of 460 Years, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 2003.

Richard Flint, No Settlement No Conquest, A History of the Coronado Expedition, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 2008.

Charles Gibson, The Aztecs Under Spanish Rule, Stanford University Press, California, 1964.

John J. Mayer and L. Lehr Brisbin, Jr., Wild Pigs in the United States, The University of Georgia Press, Athens, 2008.

Agustín Dávila Padilla, Historia de la Fundación y Discurso de la Provincia de Santiago de México de la Orden de Predicadores, Madrid, 1596.

Herbert Ingram Priestley, The Luna Papers, Florida State Historical Society, Deland, 1928.

Dr. Jacinto de la Serna, Don Pedro Ponce, Fray Pedro de Fiera (Obispo de Chiapas en 1585), Tratado de las Idolatrias, Supersticiones, Dioses, Ritos, Hechicerias y Otras Costumbres Gentilicas de las Razas Aborigenes, de Mexico, Ediciones Fuente Cultural, Mexico City, 1953, reprint of 1892 edition.

Garcilaso de la Vega, The Florida of the Inca, translated by John Grier Varner and Jeannette Johnson Varner, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1951.

Bradley J. Vierra, June-el Piper, and Richard C. Chapman, A Presidio Community On The Rio Grande, Vols. I and II, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1997.

For a good study of pigs on much earlier Spanish expeditions, See http://www.bzhumdrum.com/pig/chapter2.html for pigs in the Indies, and http://www.bzhumdrum.com/pig/chapter3.html for pigs in Mexico and la Florida.

For an interesting discussion of raising Cuban pigs versus pigs on Jamaica, See The Journal of Jamaica Agricultural Society, Volume 10, January to December, 1906, found at, https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=3HJXAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&output=reader&hl=en&pg=GBS.PP7

For further succinct reading on Spanish pigs and hams, See:

https://www.eyeonspain.com/blogs/iwonderwhy/15864/the-history-of-jamon-serrano.aspx

http://www.spainthenandnow.com/spanish-culture/jamon-iberico/default_239.aspx

- Article

-

Abstract

The Spanish financial documents related to the 1559 Luna Expedition delineate the amounts of various foodstuff shipped and the amounts paid the vendors and mule drovers for their deliveries to the Gulf port at Vera Cruz. While live pigs were a vital if not a “last resort” food source for the Soto expedition 20 years earlier, curiously the Luna records reveal that apparently no live pigs were ever sent to la Florida during that expedition—only cured or salted pork products, mainly slabs of bacon and hams.

This article will discuss the prospects of pig bones from the hams as marker artifacts for the Luna Expedition and investigate why no live pigs were ever sent to the Luna colonists in la Florida.

Salt Pork on the Luna Expedition: The Evidence

In analyzing the Spanish financial records concerning outfitting the Luna Expedition, it appears that the pork products provided for the initial sail (called the armada) to la Florida weighed over 21,000 pounds, or 10½ tons. Entries indicate that these pork products were mainly slabs of bacon (Figure 1) and hindquarters (Figure 2), which I like to call “hams” for its simplicity.

Figure 1. Slab of cured bacon, and a “slice” to the side.

Figure 2. Cured “hams” hanging in a butcher shop in Spain.

(The longer the cure, the more the cost—just like good, aged red wine.)Typically, slabs of bacon have no bones, whereas the hams would have four main bones—part of the pelvis, the femur, and the tibia and fibula (Figure 3).

Figure 3. View of a Spanish ham showing the meat cuts as well as the four main

bones—the hip bone, the femur with its large distinctive ball ends, and the

thinner tibia and fibia.(Of course, there are smaller bones associated with the hindquarters of a pig—including the hoof itself, but for the succinctness of this discussion, the small ones will not be included in this pig bone discussion—just the big ones.)

The financial records do not discern how many hams were sent versus slabs of bacon, so we cannot definitively ascertain the number of hams shipped. But knowing the Spanish demand for pork, and salt assuring a lack of spoilage and safeness from parasites; ease of cutting and weighing out rations, and versatility of hams in preparing meals, one could hypothesize that the large legs of meat (hams) made up at least one half of the total amount of salt pork.

With that mean—and each ham typically weighing an average of 30 pounds —that would approximate to at least 300 hams containing 1,200 large bones. A critic could argue that since not all the food was unloaded off the ships upon arrival at Santa Maria de Ochuse (Pensacola Bay) in August of 1559 that not all the pork products made it ashore. But with half the pork ashore, that would still be approximately 150 hams unloaded with the associated 600 bones.

On the subsequent four resupply shipments to the Luna expedition, over 30,500 pounds, or 15 tons, of salt pork products were also shipped. One could again hypothesize that half were hams, which would then equate to 500 hams with 2,000 bones. Therefore, with the possibility of the total amount of these 4 distinct possible pig bones numbering in the thousands, they could serve as marker artifacts for the location of the Luna settlement site at Santa Maria de Ochuse. Indeed, the very thick, or stout, femur—measuring about 12 inches in length with distinctive ball ends—would definitely be hard to overlook or be misidentified (Figure 4).

Figure 4. A stout femur of a pig

with its distinctive ball ends.Conversely, the long searched for Soto battle site known as Mabila on the Alabama River near the interior Luna settlement site of Santa Cruz de Nanipacana (October 1559-June 1561) would be indicated by the presence of many more different types of pig bones, especially the skulls, jawbones, and teeth from the once live pigs they slaughtered to augment their dietary needs.

Faunal remains and human remains have been found in archeological sites in northwest Florida and south Alabama dating back hundreds and even thousands of years ago. The remains were found in a variety of soil types, therefore, the prospect of unearthing the marker ham bones dating to only some 450 years is very probable.

Also, even if the Luna colonists boiled the pig bones to make a broth or fractured the leg bones for marrow extraction, the dense bones of the pigs’ femurs and hips would survive. Zooarcheologists are capable of identifying such bones as Old World ungulates (hoofed mammals).

Further—and very importantly—the salt pork served as a “ready-made” dietary supplement of salt (NaCl, sodium chloride), which is needed for all humans and other animals to survive, much less keep hydrated and endure the very hot and humid climate of la Florida. Conversely, the slaughtering of live pigs might provide the needed proteins for the colonists, but very little if any salt. Thus, casks of salt were always being sought and sent to the Luna Expedition by the viceroy—not just for seasoning foodstuff—but for the health of the expedition.

The importance of salt in la Florida is made paramount by a quote from the Soto Expedition:

There was much want of salt, also, that sometimes, in many places, a

sick man having nothing for his nourishment, and wasting away to

bone, of some ail that elsewhere might have found a remedy, when

sinking under pure debility he would say, “Now, if I had but a slice of

meat, or only a few lumps of salt, I should not thus die.”

Similarly, Luna Expedition participant Fray Domingo de la Anunciación wrote on August 1, 1560, from the chiefdom of Coosa in today’s northern Alabama:

…we people of this camp now find ourselves in extreme need of shoes—which we

are now all without—and of salt, [chili] peppers, horseshoes, and other things

without which one passes this life badly.

Therefore, the importance of salt on the Luna Expedition will be explored and discussed in a future article; and there is little doubt that salt pork served many purposes towards the health of the colonists as well as the health of the expedition.

Examples of the Spanish Financial Documents

One example of a financial entry in the Spanish records, which concerns the outfitting of the initial armada of June 1559 with pork products, reads as follows:

Miguel Carrasco, drover, was paid 18 pesos 6 tomines of the said common gold that he was owed for the delivery of 60 portions of salt pork that he brought in 6½ loads that his servant, Pero Hernandez, delivered in the said port of San Jhoan de Ulua at an amount of 2½ pesos per load as it appears by warrant of the said Alcalde Mayor dated on the said day [of May 18, 1559] and his letter of payment before the notary (Childers 1999).

Some of the entries concerning the first through third resupply shipments to Santa Maria de Ochuse read as follows:

Item: The said Pedro de Yebra presented Item: The said Pedro de Yebra presented the account for 58 pesos 2 tomines of common gold that he gave and paid to Alonso de Ledesma, drover, for the contract for the transport of 198 portions of salt pork from Mexico City to the port of San Juan de Ulua which weighted 233 arrobas for the aid sent to the governor and soldiers that were in Florida in His Majesty’s ships, at a cost of 2½ pesos for each load as it appears by warrant of the said Bachiller Martinez dated 29 January 1560 ….(Childers 1999).

Item: The said Pedro de Yebra presented the account for 22 pesos 6 tomines of common gold that he gave and paid to Juan de Mesa, drover, for the contract for the transport of 54 arrobas of portions of salt pork and 55 arrobas of hams 55 arrobas of coarse cotton shirting and six bundles of serge a leather covered chest of thread and 2 barrels of gunpowder and 29 axes that he carried from Mexico City to the port of Veracruz for the aid sent to the governor and soldiers that were in Florida as it appears by warrant of the said Bachiller Martinez dated 7 February 1560…(Childers 1999).

Item: The said Pedro de Yebra presented the account for 169 pesos of common gold that he gave and paid to Hernan Ponçe, drover, for the contract for the transport of 293 portions of salt pork, six leather covered chests and six chests that weighed 338 arrobas which he carried to the city of Veracruz for the second aid sent to the governor and soldiers that were in Florida at 4 pesos per load of 8 arrobas as it appears by the warrant of the said Bachiller Martinez dated 9 May 1560….(Childers 1999).

Item: The said Pedro de Yebra presented the account for 22 pesos 6 tomines of common gold that he gave and paid to Juan de Mesa, drover, for the contract for the transport of 54 arrobas of portions of salt pork and 55 arrobas of hams… 55 arrobas of coarse cotton shirting and six bundles of serge, a leather covered chest of thread and 2 barrels of gunpowder and 29 axes that he carried from Mexico City to the port of Veracruz for the aid sent to the governor and soldiers that were in Florida as it appears by warrant of the said Bachiller Martinez dated 7 February 1560…(Childers 1999).

Item: The said Pedro de Yebra presented the account for 169 pesos of common gold that he gave and paid to Hernan Ponçe, drover, for the contract for the transport of 293 portions of salt pork, six leather covered chests and six chests that weighed 338 arrobas which he carried to the city of Veracruz for the second aid sent to the governor and soldiers that were in Florida at 4 pesos per load of 8 arrobas as it appears by the warrant of the said Bachiller Martinez dated 9 May 1560….(Childers 1999).

And another concerning the fourth and last resupply in early April 1561 personally delivered to Santa Maria de Ochuse by the new governor—Ángel de Villafañe—reads:

Item: The said Pedro de Yebra presented the account for 92 pesos 4 tomines of common gold that he gave and paid to Diego Gutierrez, drover, for the contract for the transport of 200 portions of salt pork that weighed 252 ½ arrobas that he carried from Mexico City to Veracruz at an amount of 3 pesos per load, which was for the fourth aid that was sent to the said governor and soldiers that were in Florida and he had 2 pesos subtracted from the total because he was short 2 hams on delivery and the 92 pesos 4 tomines were what remained as it appears by certification of the said Juan Valiente and warrant of the said deputy officials dated 3 March 1561…(Childers 1999).

The latter entry indicates that the words “salt pork” and “ham” could be interchangeable, with “salt pork” perhaps the inclusive and generic term chosen by the accountant to minimize numerous micro-entries. Remember, the accountant is using a quill pen dipped in an ink bottle to write! Also, the financial record is not really about the product or service being rendered, but the MONEY and how was it spent appropriately. Therefore, the financial records pertaining to the Luna Expedition were actually an audit of how the King’s money was spent eight years after the fact! As one modern historian noted, “the Spanish Imperial administration almost never forgot anything, but it often took a long time to remember.”

The Soto Expedition and Live Pigs

Soto arrived to la Florida in May of 1539 with thirteen sows or producing female pig as a food source. He had procured the pigs in Cuba where there was an abundance of wild cows and hogs as well as domesticated herds (Figures 4, 5, and 6). It is said that Queen Isabella insisted that Columbus take eight pigs with him on his second voyage, which landed both him and the pigs in Cuba. There, the pigs quickly multiplied and eventually became a readily available and inexpensive food source for the inhabitants. Even today, pigs are a considerable part of Cuban cuisine.

Figure 5. Cuban sow with piglet.

Figure 6. Cuban sow with piglets trailing.By the following March-April of 1540 when the Soto expedition had journeyed beyond Apalachee and Patofa and into the interior of today’s Georgia, the herd of pigs had multiplied to over three hundred (Elvas 1968). Domestic pigs have a gestation period of around 121 days, and deliver around 8 piglets to a litter. A modern sow can have 1.5 liters per year, and it is possible to have a young female pig or gilt begin reproducing at 6 months. Thus, it was entirely possible to achieve the number mentioned in the records of the expedition.

When the supply of maize was used up or unavailable, Soto would order the systematic slaughtering of the pigs, allocating daily only a half pound of meat for each soldier. Another account of the slaughter relates that a pound of pork was allocated (Elvas 1968). Apparently, during this time of hunger around the Indian chiefdoms of Ocuti and Cafaqui in the Province of Altapaha, a great number of the swine were slaughtered. Interestingly, there are later accounts of hunger soon thereafter with the men eating turkeys and dogs for a meat, which were provided by the Natives (Elvas 1968)—not Soto’s pigs! Thus, one can see that Soto only employed his pigs for food when no other source was obtainable. And calculating that six hundred famished soldiers—given a ration allocation of one pound a day—could consume three to four 250-pound butchered pigs every day.

Logistically, herding swine is not that difficult. Pigs can swim and it is possible to have a sow lead her piglets across a river much like a mother duck. Likewise, with a good swineherd, Soto was able to herd his pigs all the way from mid-Florida, up through Georgia and the Carolinas, down through Tennessee and Alabama, and finally across Mississippi.

One of the last mentions of swine on the entrada is after the battle of Mauvila when Soto and his men had set up winter camp at the deserted Indian village of Chicaza in today’s northern Alabama. Eventually, in March of 1541, the Indians attacked the Spaniards within the fortified village and put it to fire. The fire was so fast and encompassing that men, women, and numerous horses were consumed (Garcilaso de la Vega 1951). The Fidalgo de Elvas recorded the following concerning the swine:

The town lay in cinders…There died in this affair eleven Christians, and fifty horses. One hundred of the swine remained, four hundred having been destroyed, from the conflagration of Mauvilla (Elvas 1968).

Garcilaso de la Vega, The Inca, presents another account concerning the remaining swine:

But since the fire on the night of the battle was so sweeping, it seized the swine also, and none of them escaped except the suckling who were able to slip between the palings of the fence, Now those animals were so fat with the great amount of food they had found in that place that the lard from them ran for a distance of more than two hundred feet, and this loss was lamented no less than that of men and horses because the Castilians suffered from a lack of meat and were saving the swine for the comfort of the sick (Garcilaso de la Vega 1951).

Thus, one can see that the pigs Soto brought had been healthy, productive, had great endurance, and importantly, possessed the instinct to survive. And since pigs can survive by literally rooting out plant parts, grubs, small rodents, etc., found in the wild, they were proven to be extremely prolific in expanding their population.

Knowing that twenty years earlier, the live pigs that Hernando de Soto brought along on his expedition to the American Southeast were very instrumental in keeping the expedition from starving, one questions why Viceroy Luis Velasco did not include swine in the planning and implementation of the initial Luna armada, much less in the subsequent aids to help sustain the Luna expedition.

The communications of the viceroy with Luna clearly indicate he was very familiar with the Soto expedition, and there were eight Soto survivor soldiers mandated by the viceroy to go on the Luna Expedition. They, too, would have been very familiar with the value of live pigs on a land expedition. Therefore, one could conclude that having pigs somewhat corralled at Santa Maria de Ochuse (Pensacola) or up at Nanipacana would have been a fruitful endeavor for the settlers on the Luna expedition—but it never happened.

On the other hand, it appears by the records that any live animal sent with or to Luna in la Florida were never realistically considered for husbandry, but quickly slaughtered and consumed by the famished population. This included sheep, goats, and cattle. In spite of this, the viceroy finally wrote to Luna on September 15, 1560, informing the governor that he intended to send the following:

In the month of January this bark or the galleon San Juan will set sail, carrying one thousand fanegas (or bushels) of corn and dried beef, a few live hogs, and such added supplies as are necessary, so that you and the people who are at the port may be maintained until you learn where the people are who went inland, and whether they have found a place where they can be maintained and fed (Priestley 1928).

However, the present records inform that such a large amount of food—much less live hogs—was never actually sent (Childers 1999, Padilla 1596, Priestley 1928). Consequently, the couple of hundred remaining soldiers and servants remaining at Santa Maria de Ochuse with Luna after much of the colonists and sick had been evacuated, again suffered great hunger from October of 1560 until the new governor Ángel de Villafañe arrived with supplies during the first week of April 1561 (Padilla 1596, Priestley 1928).

Also, the connection of finding various pig bones and designated them “marker artifacts” for a 16th-Century Spanish site demands caution as we have learned from previous interpretive errors. Indeed, in 1987 reputable archeologists excavating an early Spanish site in Tallahassee, Florida, found a pig jawbone amongst 16th-Century Spanish artifacts. The pig bone was energetically considered “positive evidence” of a Soto site. However, many years later when testing was eventually done, the pig bone turned out to be ca. 1850—over 400 years after the Soto expedition. But unfortunately, the error had already become an accepted “fact” and included in modern Soto histories and on historical plaques, further muddying the search for the allusive Soto Trail throughout the Southeast. We do not need to make the same mistake on the search for the Luna Colony.

Other Spanish Expeditions with Pigs or Only Salt Pork

Narváez in la Florida

It should also be noted that the Panfilo Narváez expedition to la Florida in 1528—according to Cabeza de Vaca—initially only had a diet of hard bread with salted pork before maize could be found and obtained from the Native population. The expedition, apparently, carried no live pigs. Cabeza recorded:

Saturday, the first of May…[Governor Narváez] commanded that each one of those who was to go with him be given two pounds of hardtack and a half a pound of salt pork. And thus we set out to enter the land.

Coronado in the American Southwest

In 1540 Francisco Vázquez de Coronado led an expedition up the western side of New Spain (Mexico) into today’s American southwest searching for gold and other riches, which were purported to be found within the fabled Seven Cities of Cibola.

Luna was a primary captain and also served as one of the maestre de campos, or head of the main camp. This position required leadership and knowledge of logistics because it involved “moving” the main force forward to support Coronado and his horse-mounted reconnaissance or advanced guard force. The advanced guard would venture many days if not weeks ahead. The maestre de campos was also in charge of food management and rations, and oversaw the herds of live animals brought along to feed the Spanish soldiers and thousands of Native soldiers who also went on the expedition. While not a “warrior” position per se, it was an esteemed and responsible position. Luna’s success serving Coronado—as well as his wealth obtained marrying a wealthy widow of two First Conquerors of Mexico—was one of the reasons Viceroy Luis de Velasco chose Luna for the la Florida expedition.

When the Coronado expedition first left the environs of Mexico City in 1540, the food herds of cattle, sheep, and hogs numbered in the thousands. Participant Melchor Pérez testified later that he had taken 1,000 hogs and sheep valued at around 1,200 pesos (Flint 2003). However, by the time the expedition had ventured beyond the relative comfortable temperature of the plateau of central Mexico and into the arid and sunbaked grasslands and deserts of today’s Arizona and New Mexico, it appears that only the grazing animals—cattle and sheep—remained for food stock. The cattle tallied around 500 and sheep around 5,000 (Flint 2003). The bones from these non-native animals have served archeologists to identify several Coronado sites (Vierra 1997).

Why No Live Pigs with Luna?

The question of “why no live pigs were ever sent with or to Luna in la Florida” still begs an answer. Was the micro-manager Viceroy Velasco remiss in choosing the appropriate “food supply,” or were there other factors? As stated before, his letters written to Governor Luna during the expedition indicate—without doubt—that the viceroy was very familiar with all aspects of the Soto expedition and the ever growing swine herd Soto took along. The answer may lie in many possibilities. Presented below are some that will be considered, as well as an unusual one that speaks to the “jinxed” nature of la Florida and the expedition itself.

- Realism

- Practicality

- Availability

- Logistics of rations

- Salt for the health and survival of the expedition

- Superstition

1) Realism:

Any live food animals brought on the initial armada or sail to Santa Maria de Ochuse appear not to have completed the voyage. It is most probable that any feed set aside for such animals for a 15-day voyage likely ran out during the 45-day extended sail, or got sick and died, or were consumed by the peoples on board the ships. Any live food animals sent on the subsequent resupplies to Santa Maria de Ochuse for the starving and dying peoples of the Luna Expedition would not have lasted a day upon arrival, especially after the devastating hurricane; such food sources would have been roasting over a fiery pit before the evening! Eleven calves sent on the first resupply to Santa Maria de Ochuse around November 1559 appear never to have been allowed to mature. And by the time the expedition was located up at Nanipacana, even posting guards would have been futile inasmuch as the disobedient soldiers would have rather been hung and experienced a quick death for their thievery than to continue to suffer a slow death via starvation. While we presently do not have the original letters Luna wrote to Viceroy Velasco, it is probable that Luna informed the viceroy that salted pork and hams would be more appropriate to be sent over live animals as the rations could be better kept under lock and key, appropriately weighed, and allocated to the peoples. Also, while hogs can practically survive on anything they can put in their mouths there was no food—not even wild vegetation within miles—that the hogs could live upon and multiply. The Native population had scorched and laid bare the surrounding lands of everything edible that even the horses had no grasses to graze upon and could barely support a mount.

Also, it should be noted that the swine brought on the Soto Expedition survived “illegal slaughtering” even during periods of severe hunger by the soldiers because Governor Soto owned the swine. Only he could allocate or order the killing of his herd; and it is likely Soto would have slowly tortured and killed or set the war dogs on anyone that stole his personal possessions. Indeed, in March of 1540—during a trek through an unpopulated area without a Native population—to obtain foodstuffs, Soto finally ordered some of his own swine killed to appease the great hunger of his men.

2) Practicality:

This factor is somewhat based on the 1st, but also addresses the nature and “occupations” of the soldiers and colonists on the expedition.

Basically, although the expedition had brought along and unloaded tools for farming, the peoples and soldiers were not from farming backgrounds, much less experienced in animal husbandry. Farming in la Florida—as was experienced in Mexico—was mainly to be relegated as the tasks of the Native populations, once they had been subjugated. Having haciendas and owning herds of cattle and other grazing stock were the dreams of the colonists, and that is why they had sought their fortune on the expedition. Most of the colonists had nothing to lose by venturing to la Florida, having left anything behind in Mexico; otherwise they would have never sought opportunity and a life elsewhere! Viceroy Velasco recognized this fact, and wrote Luna that experienced farmers could eventually be solicited from Spain.

3) Availability:

While the Spanish had introduced cattle, goats, sheep, and pigs to New Spain after the Conquest of 1521, the wide acceptance of these foodstuffs at the time of the 1559 Luna Expedition by the Native population was still minimal. Animal husbandry was more domestic in character and relegated to the hands of the Native women around their households, rather than being a distinct male profession—raising such animals in great numbers as a business. However, the introduction of herds of cattle in the valleys around Oaxaca by the Spanish became so destructive to the native crops of that fertile valley that cattle were outlawed by the viceroys. This destruction problem was also similar with the introduction of pigs and sheep herds. Therefore, (besides fish) the traditional and transitional native diet for meat was satisfied through the limited raising of ducks and geese, pigs and goats, rabbits, native dogs, and even coyotes. Thus, to satisfy the pork needs of the non-farming Spanish population in Mexico City, Spanish entrepreneurs developed large pig farms located near the main roads and close to the city. This included Apam (northeast at 88 kilometers), Calpulalpan (east-northeast at 72 kilometers), and Toluca (west-southwest at 68 kilometers).

Utilizing the main connecting roads, herding or even carting the pigs to market in Mexico City would only require a couple of days, and one of the main places where salt was obtained to cure the pork was located in the southern lake area upon which Mexico City was situated. Thus, the area in and around Mexico City was more of the central area for large swine production and processing—not along the coastal areas near the port of Vera Cruz. Therefore, hauling vast amounts of salt pork on the backs of mules from Mexico City to Vera Cruz was the preferred option to supply the Luna Expedition.

Also, the period records show that the meals provided by the Native women for the overland trek of the expedition on the road from Mexico City to the departure point at Vera Cruz only included tortillas comprised of hens, eggs, maize, frijoles, chili peppers, and fish—but no pork products; and only the labor to make the meals was considered an expenditure by the Spanish. The contribution of foodstuffs was part of the old tributes previously imposed by the Aztec rulers and continued by the Spanish. Conversely, the newly imported Old World pigs were not part of the old tribute and therefore any pigs the Natives might have been raising within their small compounds were not offered up in tribute. Pork products would have to be purchased by the Crown.

4) Logistics of Rations:

When cutting a freshly roasted pig it is harder to allocate and weigh for procuring ration portions as the moisture content varies, and it also involves who gets warm meat and who near the “end of the line” gets the cold meat. This problem could affect the morale of the soldiers—not among the officers and Royal Officials who would surely have gotten hot portions—but among the common soldiers and colonists. The servants, forced laborers, and the Aztecs along on the expedition would probably have been just glad to receive any foods—hot or cold! And even if you had many roasting pits cooking at the same time, feeding over 1,500 persons was still a logistic nightmare.

However, in salted pork—bacon or ham—the meat is very consistent and all “cold” portions could be allocated at an equal and fair weight. Thus, it would be left to each individual or groups to warm or cook their meats at their own discretion and ability to prepare a cooking fire. This would of course also depend upon the ability of the serving people and women and children to collect the appropriate firewood needed to prepare a hot meal.

5) Health and survival of the expedition:

Most of the Spanish soldiers and colonists on the Luna Expedition heralded from the central, high plateau regions of New Spain where the comfortable, mild temperatures afforded a fairly healthy climate year round, even during the summer months. Therefore, it was possible to perform heavy labor without an excess of sweat that the humid hot seasons in la Florida wrought. The salt in the salt pork products found around Mexico City could have supplied most of that necessary nutrient without much supplement.

However, knowledge from the Soto survivors of the known climates of la Florida required that the Luna Expedition take along casks and leather baskets of salt to augment the dietary requirements.

The financial entries mention the sending over 100 fenegas (Spanish bushels) of salt for the initial armada in June 1559. However, by the time the Viceroy Velasco discusses in October of sending the first resupply ships after the devastating hurricane and two months of intense summer heat, he writes that he will also have a bark built at the coastal city of Panuco—north of Vera Cruz and a “safer coastal sail” to Pensacola Bay—whereby to take salt, live cattle, and other needed provisions.

While the subsequent resupply shipments also record the sending of more salt, one must also consider that perhaps the salt pork (and some barrels of salt meats) were also designed to provide the peoples with a “built in” salt allotment within their food sources. That is something live pigs could not achieve.

6) Superstition:

Atlantic seamen in the West Indies (at least as recorded by the 1600s) had a bizarre superstition related to swine. Pigs themselves were held at great respect because they possessed cloven hooves just like the “devil” and the pig was the signature animal for the Great Earth Goddess, who controlled the winds. As a result, these fishermen never spoke the word “pig” out loud, instead referring to the animal by such safe nicknames as Curly-Tail and Turf-Rooter. It was believed that mentioning the word “pig” would result in strong winds. Actually killing a pig on board the ship would result in a full scale storm.

This becomes relevant to the Luna Expedition in that mariners were afraid to sail to Pensacola Bay because of the reputation of la Florida and its distant ports plagued by hurricanes and “murderous” Native populations who would kill any survivors of shipwrecks. The shipwrecks and ultimate deaths of survivors of the treasure fleets of 1545, 1553, and 1554 on the coasts of “la Florida” were clearly still on the minds of the peoples in New Spain. Further, the deaths of prominent Dominican fray Luis Cancer and his companions on their missionary expedition to the coast of la Florida in 1549 made the possible peaceful interaction amongst the Natives a very questionable enterprise. Indeed, the outfitting of the first reconnaissance expedition, led by Guido de la Bazares to rediscover Ochuse in 1558 in preparation for the Luna Expedition the following year, included much personal armament for the soldiers that were to go along as well as harquebuses and a variety of light and heavy cannons for protection.

Thus, word of the devastating hurricane upon the Luna fleet in September 1559 brought much distress in New Spain because of the belief that the expedition was perhaps doomed from the start by the hand of God.

“…If you had not gone out toward the open sea as you did, you would have reached it [Pensacola Bay] some days sooner; if the pilots had been able to do so they would have saved time and labor and the loss of some of the horses, and possibly the loss of the ships. But since our Lord ordained it thus there is nothing to be said except to give Him many thanks, and pray to Him that in what remains for you to do. He will guide, enlighten, and assist you…I trust in the Lord that He will give you your reward for them in this life and the next.”

Indeed, the hurricane “was sent upon the expedition” on a Sunday—the Holy Sabbath! The thought or idea that God would allow such destruction on “His Day” would have had many contemplating and asking, “What had they done to deserve this punishment?” Was it their gluttony while on the ships? Religious historian Dávila Padilla noted in his 16th-Century narrative that, “there was enough food in the ships for over a year, even though it was being excessively eaten by the 1500 persons that were there.” And had not everyone been properly dedicated with the zeal as they should have been and were more concerned with their own comforts and well-being than the mission at hand, which included the conversion and saving of many Native souls? Again, Dávila Padilla writes of the arrival of the expedition to the shores of Pensacola Bay and mentions what might be considered an “initial weakness” before tackling the job at hand:

When the new settlers saw themselves in such a peaceful place, for some days they enjoyed the freshness of the place and the gift of the tide. Some sat down on the sand before the Sun could heat them and others when the evenings after the sunset, made them cool, exercised the horses, showing off their finery and dexterity: others went in the barks and coasted the shore. Others considered it from the land, regaling themselves with the view of the meek waves, which as they were peaceful and gentle, arrived calmly to the shore and without going astray, they returned to the sea. They arrived as if to greet those on the land, retreating from them without disturbing anything. Finally,{those that had gone in the barks, and} those that crewed them all rejoiced together because it is not only an entertaining thing to go together to the sea but also to sail close to land. But as the voyage had not been to look for recreational activities nor to hold fiestas, then true things were discussed, and an order given to enter and explore the land, and to give his Majesty an advisory on what had happened in compliance with his royal cédula.

Compounding all of this, the mariners that could be found in New Spain were afraid Governor Luna at Santa Maria de Ochuse would “impress” the seamen in service on the land, as he had done with common mariners who survived the hurricane, but lost their ships in the waters of Pensacola Bay. As a result, Viceroy Velasco specifically instructed Luna that “all [the mariners] who go [on the resupply ships] may freely return, and some of those that were saved from the ships that were lost and who have wives in Spain you will send back in order that they may collect the wages which are due them and go home from here.”

There can be little doubt that the recruitment of scarce seamen in New Spain to man the resupply ships destined for the Luna Expedition—full of food provisions for the starving soldiers and settlers—was a factor in the many delays that always seemed to plague the la Florida expedition. Indeed, the record is replete with others hiding from the commands of the viceroy—and therefore the will of their King—especially to avoid a trip to la Florida.

Conclusion

The unearthing of a substantial quantity of “ham bones”—along with Mexican-style metates and Christian burials as discussed in previous articles (Dodson 2016, 2017) in concert with other features—such as numerous fire hearths, refuse pits, and remnants of structures—would all indicate if not verify a Luna settlement site in Pensacola (Curren 2017). Otherwise, finding 16th-Century Spanish artifacts mixed with Native artifacts only indicates Native contact with one or more Spanish entradas during the 16th Century. This could include early contact and trade by Native populations with the 1528 Narvaez Expedition or the 1540 Soto Expedition or the Luna Expedition or interaction with Spanish slavers or a combination of all of the above.

Also, the question of why no live pigs were ever sent to the Luna colonists in la Florida is still not fully answered. More research into the Spanish records must be initiated to discern a more definitive answer.

For now, it appears that the soldiers and colonists on the Luna Expedition did not enjoy “a grand pig roast” of freshly butchered swine, only meals of salted pork in “sandwiches,” which manifested themselves as one of the ingredients in their tortilla rations. As such, what remaining leg bones from the tons of salted pork sent to Pensacola Bay should serve as additional marker artifacts to indicate the Luna settlement site of Santa Maria de Ochuse at today’s Pensacola Bay; and to a lesser extent, the site of the Luna settlement at Santa Cruz de Nanipacana on the lower Alabama River.

- References and Related Works

-

Sources

Peter Bakewell, in collaboration with Jacqueline Hollar, A History of Latin America to 1825, 3rd Edition, Wiley-Blackwell, United Kingdom, 2010.

Fletcher S. Bassett, Legends and Superstitions of the Sea and Sailors, Singing Tree Press, Detroit, 1971, facsimile of 1885 edition.

Pedro de Castañeda de Nájera, ed. John Miller Morris, Narrative of the Coronado Expedition, R.R. Donnelley & Sons Company, Chicago, 2002.

Wayne Childers, Translation, AGI. Contaduria 877, 1999.

David B. Dodson, unpublished manuscript concerning new documents, translations, and corrected aspects of the present narrative of the Luna Expedition, 2002-till present.