Etowah Was the Coosa of De Soto

by Jeffrey P. Brain

(2024)

In my 1985 review of the state of knowledge concerning the route of the Hernando De Soto entrada through the southeastern United States in 1539-1543, I reached a discouraging conclusion: “… at this writing the presence of De Soto has not been established [at a specific geographic location] beyond doubt anywhere” (Brain 1985b, p. xlvi). Many hypotheses had been proposed and many artifacts reasonably attributed to a mid-sixteenth-century Spanish expedition had been found, but these only traced a general passing of the army, not actual footsteps and campsites of the army itself.

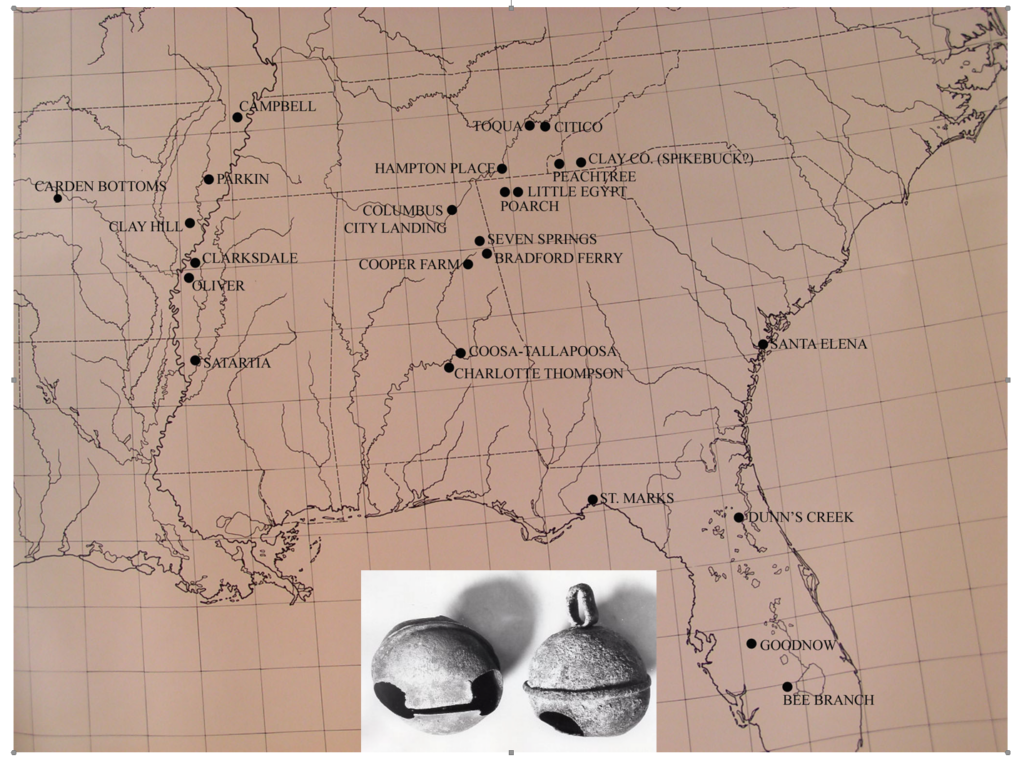

Distinctive early 16th century artifacts, such as Clarksdale bells (Brain 1975)), are indicative of Spanish contact. While bells Florida and along the coast could have been distributed by other explorers, those in the interior closely match the general route of the De Soto entrada. (It could be that some of the Alabama, even the Tennessee, examples were left by the slightly later Luna or Pardo expeditions where their routes may have overlapped that of De Soto.)

This is no longer true. During the decades since then, several reasonably secure locations for the actual presence of the army have been identified. These include the Martin site in Florida [Anhaica] (Ewen and Hann 1998), the Heritage and related sites in Georgia [Capachequi] (Blanton 2020, p. 188, 2023), the Glass site in Georgia [Ichisi] (Blanton 2011, 2020, pp. 191-192), and the Berry site in North Carolina [Xuala] (Beck et al. 2006, 2016).[1] Other probable locations that require more definitive proof are the Tatham site in Florida (Mitchem 2019, 2021), the Peachtree site in North Carolina [Guasili?] (Setzler and Jennings 1941), the Oliver site in Mississippi [Quizquiz?] (Brain 1975), and the Parkin site in Arkansas [Casqui?] (Mitchem 2019, 2021).[2]

As such points become proven it will be possible to discard the flawed “long ribbon” approach for tracing the route of the army (as proposed in many articles by Charles Hudson and colleagues, e.g., Hudson et al. 1987; Milanich and Hudson 1993, p. 6; Smith 2000, p. 84), and proceed from known data points in the “connect-the-dots” approach (Brain 1985b, 1998). There are still large gaps, however, and one of these – which could be a lynchpin to the route of the expedition – is described in the chronicles as one of the greatest of all native chiefdoms visited by the army. Identified as Coosa [Coça], it was a very large province which modern scholars place generally within the tri-state region of southeastern Tennessee, northwestern Georgia, and northeastern Alabama.

The chief of Coosa led the Spaniards into his capital town, which clearly made an impression for it was larger than those previously encountered and was dominated by three great mounds. De Soto was given residence on one of these mounds and his army was camped nearby. They stayed in Coosa for more than a month, which would have been sufficient time to leave a significant archaeological footprint. And, indeed, numerous European artifacts diagnostic of the mid-sixteenth century have been found at the greatest mound site in the region, Etowah (Smith 1976; Brain and Phillips 1996, p. 173; King 2003, p. 82). Why, then, has Etowah not been accepted as the capital of Coosa described in the De Soto narratives?

According to (generally perceived) conventional wisdom, the great site had passed its peak, and in fact had been abandoned by 1375, and then was only briefly reoccupied by a small population during the sixteenth century (King 1999, 2003, fig. 8, table 1, pp. 81-82; see also Hudson et al. 1985, 1989; Smith 2000, pp. 29, 92; Le Doux 2010). So, according to these authors, it could not have been Coosa. Instead, the laurels were bestowed upon the Little Egypt site (King 2003, p. 133; Hudson et al. 1985; DePratter et al. 1985; Hally et al. 1990; Hally 1994; Smith 2000, pp. 35, 84), a nearby minor mound site that does not match the impressive accounts of Coosa described in the narratives, but does have a few probable De Soto era artifacts (Moorehead 1932, pp. 152-154; Brain and Phillips 1996, p. 197) and it fits better the reconstructed route of Hudson and his colleagues. That reconstruction has been critiqued elsewhere (Boyd and Schroedl 1987) and only concerns us here in regard to the all important location of Coosa. The case for Etowah being De Soto’s Coosa has been convincingly argued by Keith Little (2008, pp. 185-232) and needs only to be summarized and elaborated upon here.

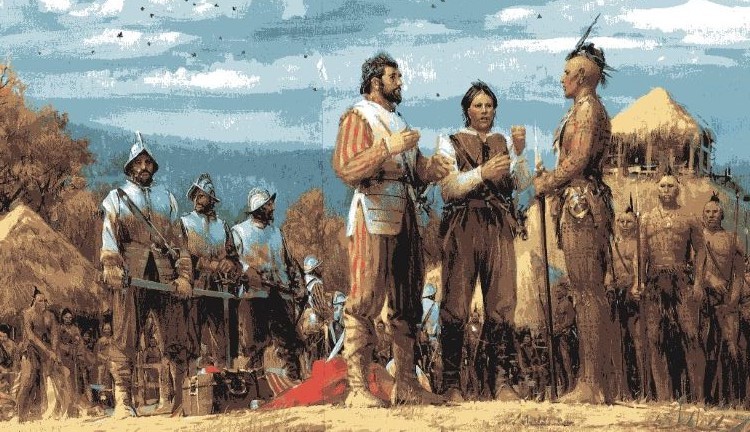

First, let us examine the narratives a little further. Coosa was widely renowned among the natives and when De Soto learned of it early in 1540 it clearly became an objective of the entrada. When they reached Coosa all the chroniclers agreed that it was, indeed, one of the most important chiefdoms they had encountered (Clayton et al. 1993, vol. 1, pp. 92-93, 232, 284, vol. 2, p. 322). When they approached the capital town, the Spanish must have been encouraged, for they were greeted by the great chief who was clothed in ceremonial regalia, was borne on a litter by his “nobles,” and was accompanied by musicians. All of the chroniclers make special mention of this display (ibid.). The scene is reminiscent of a “Big Man” display in the same mold, if smaller scale, as that of the Incan Atahualpa whom De Soto had witnessed in Peru. Although the prospect of another golden kingdom, the objective of the conquistadores, would have been badly tarnished after a year of disappointments, a glimmer of hope must have been rekindled.

The capital town of Coosa was also impressive. Most of he towns visited by the entrada were not described because to the conquistadores they all looked alike: “Thus having seen one pueblo we have seen almost all, and it will not be necessary to describe them separately unless one appears so different that it requires an account of its own” (ibid.,vol, 2, p. 185 emphasis supplied). Thus only in exceptional cases was a “pueblo” described and such was the case at Coosa (ibid., vol. 2, pp. 322-324):

They lodged the governor in one of three houses that the curaca had in different parts of the pueblo, built in the same form as we have said other such houses were, situated on a height with the advantages that the lord’s houses have over those of his vassals. The pueblo was established on the bank of a river and had five hundred large and good houses, which showed clearly that it was the head of a province so large and important as has been said. They had moved out of half the pueblo (in the vicinity of the governor’s lodgings) where they quartered the captains and soldiers, and there was room for all of them because the houses would accommodate many people.

Although the above quotations are from Garcilaso, similar impressions are expressed by the other chroniclers in their more abbreviated accounts (ibid., vol. 1, pp. 92-93, 232, 284). So Coosa, then, was a very large town with three especially notable mounds, and the only such site in the general vicinity of the south Appalachian region acceptable as the probable location of Coosa is Etowah.

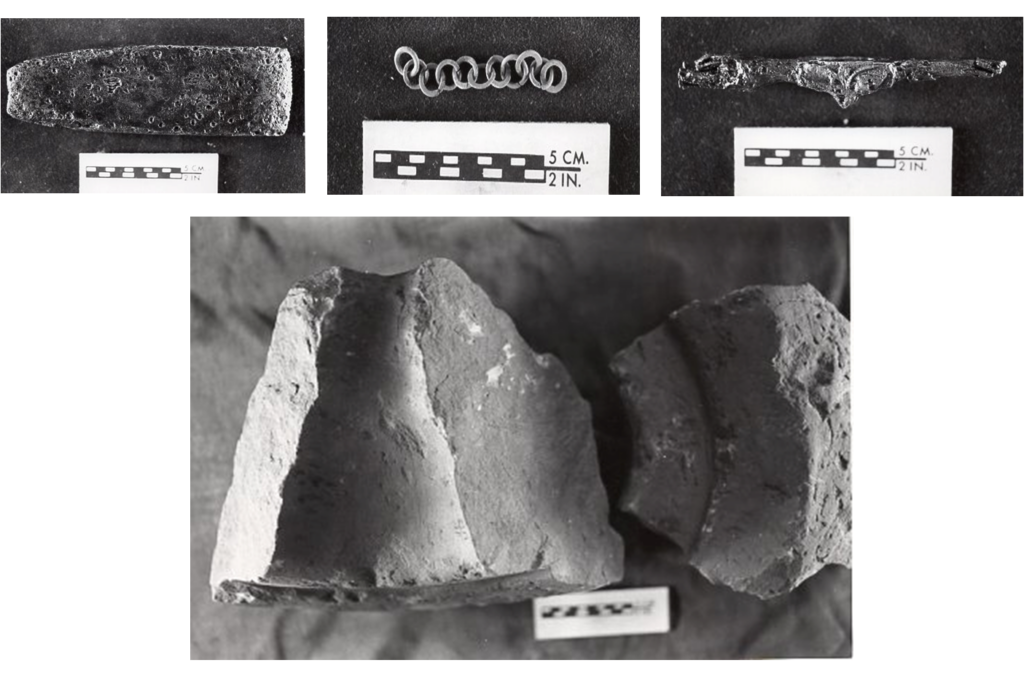

Archaeological evidence for a Spanish presence at Etowah is found in the appropriate mid-sixteenth-century European artifacts that have been recovered from the village area east of Mound A and around Mound B – on which De Soto might have been lodged – where the majority of the soldiers would have camped. These include an iron auger bit, an iron celt, a brass chain (mail?), and the cross piece from a sword hilt.[3] A lead ball and horse bones were found on a house floor (King 1996, p. 127).

Especially of note are two fragments of a portable beehive-shaped rotary sandstone quern of obvious European origin, which would have been a necessity for an army on the march living off Indian corn that they gathered along the way. These two quern fragments were found on the floors of two different houses, both of which also contained Lamar pottery.

That these artifacts can be ascribed specifically to the De Soto entrada and not the slightly later Luna expedition is apparent in the fact that Luna never visited Etowah. Although Luna had veterans of the De Soto entrada as guides, the Coosa they found was not anything like the Coosa described in the De Soto narratives (Priestly 1928, p. 241; Smith 2000, pp. 42-43):

It was God’s will that they should soon get within sight of that place [Coosa] which had been so far famed and so much thought about and, yet, it did not have above thirty houses, or a few more … It looked so much worse to the Spaniards for having been depicted so grandly, and they had thought it to be so much better … Those they had brought along as guides,being people who had been there before declared that they must have been bewitched when this country seemed to them so rich and populated as they had stated.

Their bewilderment is obvious. What had happened? Coosa had moved in the intervening decades. Etowah had been abandoned after De Soto’s devastating visit and the remnant population had migrated to the Weiss Lake region of northeastern Alabama. This removal is elegantly proven by Keith Little (2008, pp. 233-238).

Archaeological evidence of De Soto’s destructive impact upon Etowah might be found in the unique Burials 1 and 15 excavated at the mortuary Mound C by Lewis Larson (1971, p. 65):

Burial 15 was a log tomb built in a pit that had been dug at the base of the ramp on the eastern side of the mound … Included in the tomb were parts of the dis-membered bodies of 4 individuals. In addition to the scattered skeletal material were two large stone human effigies, stone and clay pipe bowls, shell beads, copper covered wooden ear discs, antler projectile points, and fragments of sheet copper hair ornaments. The floor of the tomb presented a picture of complete disarray. The stone effigies were broken, apparently accidentally, as a consequence of dropping one upon the other as they were being placed in the tomb. The other objects and parts of bodies were scattered over the floor of the tomb without any obvious design.

This feature is not anything like the other carefully placed burials found elsewhere within the mound. The scattered human remains, artifacts, and broken effigies would suggest that the term “burial” is a misnomer for it does not appear to have been a proper mortuary event at all. The impression grows stronger with the description of Burial 1 (ibid.):

By all appearances, Burial 1 followed almost immediately after 15 (my own concept of the time separation between the two burials is in terms of hours), and may be interpreted as the final aboriginal activity carried on at the mound. Burial 1 was not placed in a pit, tomb, or any sort of enclosing device. It, too, consisted of portions of dismembered bodies of at least 4 individuals, all or some of whom may also have been included in Burial 15. The skeletal material was scattered over the surface of the lower portion of the ramp for a distance of 10 ft upward from the base. The burial lay over the pit containing Burial 15. Mixed with the skeletal material of the burial were a variety of objects: a stone palette, shell beads, copper covered wooden ear discs, a pipe bowl fragment, antler projectile points, large sections of pottery vessels, whose shapes embraced a number of unusual bottle and jar forms, and a quantity of marine shells including welks and oysters. All of this was covered by a dark, heavily organic loam that contrasted with the sterile clays used in the different construction phases of the mound that underlay Burial 1.

As suggested by Brain and Phillips (1996, pp. 174-175) these “burials” may actually represent an extraordinary sequence of destruction quite at odds with the orderly ceremonial activities otherwise exhibited in the mound. It is not unreasonable to envision a single catastrophic event carried out by fanatical intruders who ripped the stone idols from their place of honor in the mound-top temple/charnel house and hurled down the ramp of the mound into the open pit (perhaps a prepared tomb that had not yet been used?) with such force that they were smashed into fragments; then the despoiled human and artifactual contents of the charnel house were tumbled down the ramp of the mound, overflowing into the same open pit, and, finally, all was haphazardly covered by the final detritus of disaster. While such an event could have been carried out by native adversaries (e.g., Clayton et al. 1993, vol. 2, pp. 397-398), it has all the hallmarks of a typical modus operandi of the conquistadores when native religious structures were encountered. For example, in Mexico (Prescott, 1986, pp. 195, 427):

Fifty soldiers, at a signal from their general, sprang up the great stairway of the temple,entered the building on the summit … tore the wooden idols from their foundations, and dragged them to edge of the terrace … they rolled the colossal monsters down the steps of the pyramid.

With shouts of triumph, the Christians tore the uncouth monster from his niche, and tumbled him, in the presence of the horror-struck Aztecs, down the steps of the teocalli. They then set fire to the accursed building.

And in Peru, where De Soto would have been a witness (participant?) to such depredations (Prescott 2005, p. 234):

Pizarro was refused admittance by the guardians of the portal. But … he forced his way into the passage, and, followed by his men, wound up the gallery [stairway?] which led to an area on the summit of the mount, at one edge of which stood a sort of chapel. This was the sanctuary of the dread deity … Tearing the idol from its recess, the indignant Spaniards dragged it into the open air, and there broke it into a hundred fragments.

Such an act of despoliation would seem to indicate a catastrophic conclusion to the use of Mound C at Etowah and, since Mound C represents Etowah at the apex of its development, a Spanish agency would date the end of this great site to 1540.

Evidence of a De Soto presence at Etowah is thus quite compelling, so why does conventional wisdom continue to reject it as Coosa? It comes down to a matter of chronology, that most basic tool of archaeology. The problem here is that some late prehistoric events in the Southeast, and specifically the Southern Cult (SECC) phenomenon, in which Etowah’s participation is abundantly evidenced at Mound C, have been incorrectly dated to the period A.D. 1200-1350. But after an extensive review of contexts across the Southeast that contained SECC artifacts, it has been argued that the phenomenon actually dated after A.D. 1350 (Brain and Phillips 1996). At Etowah, the SECC is manifested by diagnostic artifacts found in ceremonial contexts within Mound C, which is the prime feature of the Wilbanks phase of occupation. The currently proposed dating of Mound C is based upon a series of radiocarbon dates (King 2003, table 11). However, it seems that those dates have “little to offer in the way of information about the dating of Mound C” … because “there is little internal integrity to those dates.” So they are simply averaged for “a result that falls in the middle of the thirteenth century” (ibid., pp. 151-154), which, of course, conveniently fits within the A.D 1200-1350 dating that conventional wisdom currently ascribes to the SECC. Having thus supposedly found its chronological home, the site is then claimed to have been abandoned and the Wilbanks phase ended by A.D. 1375 (ibid., table 1, p. 92; Smith 2000, p. 30).

However, while many of the artifacts from Mound C at Etowah are exemplars of the SECC, they also were found in closed contexts with other imported artifacts, as well as local Lamar pottery, that clearly date to a later period after AD 1350 (Brain and Phillips 1996, pp. 132-175). In the local chronology, Lamar pottery defines the Brewster phase, which represents the supposed reoccupation of Etowah by a small population after A.D. 1475. Normal archaeological procedure is to date a context by the latest artifacts found within it, so it would seem apparent that there was no abandonment and no gap in occupation after A.D. 1350 (ibid., p. 174).[4] Instead, Etowah continued to flourish during the following two centuries – when the SECC was at its height – until disaster struck. As Keith Little concluded after an exhaustive review of the artifactual and chronometric evidence from Mound C, “artifact accompaniments in Mound C final mantle burials date nearer to the time of initial European contact than to the fourteenth century and … the site was continuously occupied from Wilbanks time well into the sixteenth century” (2008, p. 214; see also Brain and Phillips 1996, p. 174).

A few examples of imported terminal prehistoric–protohistoric artifacts found in Mound C. Painted pottery from the Mississippi Valley and a tortoise-shell bird-head pin from Florida.

Illustration reproduced with permission: John Berkey Art Ltd. ©

So was Etowah the Coosa of De Soto? Yes it was, and in that fact lie two important lessons. First, that the final decline manifested at Etowah, and probably Moundville, Lake Jackson, and many other sites throughout the Southeast was due, not to native failures, but to European intervention (Brain and Phillips 1996, pp. 2, 397). Second, that without a firm chronological foundation, those interpretations of the past that we all seek are little more than “just-so stories.”

Endnotes:

[1] Also probably visited by Pardo only a few years later, so it may be impossible to distinguish between the artifacts from the two expeditions.

[2] That Quigualtam was located at the Emerald site in southwestern Mississippi is a reasonable hypothesis, but since De Soto only sent a small delegation to meet briefly with the great chief of the proto-Natchez there would be no physical evidence of the army there (Brain et al. n.d.).

[3] This crosspiece is identical to that on another sword that was found at the King site (Smith 2000, pl. 3a) which has been dated to 1530-1540 by Dr. Sarah Bevan, Keeper of Edged Weapons, H.M. Tower of London (pers. Comm. to JPB 1987).

[4] In the regional chronology, two minor phases, Stamp Creek and Mayes, have been inserted into this supposed gap, but these are essentially ghost phases based solely upon a few minor ceramic decorative and rim modes of Lamar pottery (King 2003, p. 32) and they are not even represented at Etowah.

Bibliography

Beck, Robin A., Jr., David G. Moore, and Christopher B. Rodning

2006 Identifying Fort San Juan: A Sixteenth-Century Spanish Occupation at the Berry Site, North Carolina. Southeastern Archaeology, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 65-77.

Beck, Robin A., Jr., Christopher B. Rodning, and David G. Moore, eds.

2016 Fort San Juan and the Limits of Empire: Colonialism and Household Practice at the Berry Site. University Press of Florida. Gainesville, Florida.

Blanton, Dennis B.

2011 Points of Contact: The Archaeological Landscape of Hernando de Soto in Georgia. Final Technical Report, Fernbank Museum of Natural History. Atlanta, Georgia.

2020 Conquistador’s Wake: Tracking the Legacy of Hernando De Soto in the indigenous Southeast. University of Georgia Press. Athens, Georgia.

2023 Archaeological Identification of Historically Referenced Sixteen-century Native Provinces: the Example of de Soto’s Capachequi. Southeastern Archaeology, vol. 42, no. 4, pp. 290-310.

Boyd, C. Clifford, and Gerald F. Schroedl

1987 In Search of Coosa. American Antiquity, vol. 52, no. 4, pp. 840-844.

Brain, Jeffrey P.

1975 Artifacts of the Adelantado. The Conference on Historic Site Archaeology Papers, vol. 8, pp. 129-138.

1985a The Archaeology of the Hernando de Soto Expedition. In R. Badger and L. Clayton, eds., Alabama and the Borderlands: From Prehistory to Statehood. The University of Alabama Press. University, Alabama.

1985b Introduction. Final Report of the United States De Soto Expedition Commission, by John R. Swanton. Classics of Smithsonian Anthropology Reprint. Smithsonian Institution Press. Washington, D. C.

1998 A Note on the River of Anilco. Mississippi Archaeology, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 115-124.

Brain, Jeffrey P., Ian W. Brown, and Vincas P. Steponaitis

n.d. Archaeology of the Natchez Bluffs. Unpublished ms. Research Laboratories of Archaeology, University of North Carolina. Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Brain, Jeffrey P., and Philip Phillips

1996 Shell Gorgets: Styles of the Late Prehistoric and Protohistoric Southeast. Peabody Museum Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Clayton, Lawrence A., Vernon J. Knight, Jr., and Edward C. Moore, eds.

1993 The De Soto Chronicles, 2 vols. The University of Alabama Press. Tuscaloosa, Alabama.

Cobb, Charles R., and Adam King

2006 Re-Inventing Mississippian Tradition at Etowah. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 167-192.

DePratter, Chester B., Charles M. Hudson, and Marvin T. Smith

1985 The Hernando de Soto Expedition: From Chiaha to Mabila. In R. Badger and L. Clayton, eds. Alabama and the Borderland: From Prehistory to Statehood. The University of Alabama Press. University, Alabama.

Ewen, Charles R., and John H. Hann

1998 Hernando de Soto Among the Apalachee: The Archaeology of the First Winter Encampment. University Press of Florida. Gainesville, Florida.

Hally, David J.

1994 The Chiefdom of Coosa. In C. Hudson and C. C. Tesser, eds. The Forgotten Centuries. The University of Georgia Press. Athens, Georgia.

Hally David J., Marvin T. Smith, and J. B. Langford

1990 The Archaeological Reality of De Soto’s Coosa. In D. H. Thomas, ed. Columbian Consequences. Smithsonian Institution. Washington, D. C.

Hudson, Charles M., Chester DePratter, and Marvin T. Smith

1989 Hernando de Soto’s Expedition through the Southern United States. In J. T. Milanich and S. Milbrath, eds. First Encounters. University Presses of Florida. Gainesville, Florida.

Hudson, Charles M., Marvin T. Smith, David J. Hally, Richard Polhemus, and Chester DePratter

1985 Coosa: A Chiefdom in the Sixteenth Century Southeastern United States. American Antiquity, vol. 50, no. 4, pp. 723-737.

1987 Reply to Boyd and Schroedl. American Antiquity, vol. 52, no. 4, pp. 845-856.

King, Adam

1996 Tracing Organizational Change in Mississippian Chiefdoms of the Etowah River Valley, Georgia. Ph.D. Dissertation. Department of Anthropology, Pennsylvania State University. University Park, Pennsylvania.

1999 De Soto’s Itaba and the Nature of Sixteenth Century Paramount Chiefdoms. Southeastern Archaeology, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 110-125.

2003 Etowah: The Political History of a Chiefdom Capital. The University of Alabama Press.Tuscaloosa, Alabama.

Larson, Lewis

1971 Archaeological Implications of Social Stratification at the Etowah Site, Georgia.” Society for American Archaeology Memoir, no. 25, pp. 58-67.

LeDoux, Spencer C.

2010 The Fall of Etowah, A. D. 1375: Warfare in the Iconographic Record. Field Notes: A Journal of Collegiate Anthropology, vol. 2, art. 4, pp. 37-49.

Little, Keith J.

2008 European Artifact Chronology and Impacts of Spanish Contact in the Sixteenth-Century Coosa Valley. Ph.D. Dissertation. Department of Anthropology, The University of Alabama. Tuscaloosa, Alabama.

Milanich, Jerald T., and Charles M. Hudson

1993 Hernando de Soto and the Indians of Florida. University Press of Florida. Gainesville, Florida.

Mitchem, Jeffrey M.

2019 Two Archaeological Snapshots of the Hernando de Soto Expedition. Paper presented to the Florida Anthropological Society. Arkansas Archeological Survey. Fayetteville, Arkansas.

2021 A Diachronic Perspective on the Hernando de Soto Expedition. In A. S. Cordell, and J. M. Mitchem, eds. Methods, Mounds, and Missions: New Contributions to Florida Archaeology. University Press of Florida. Gainesville, Florida.

Moorehead, Warren K.

1932 Exploration of the Etowah Site in Georgia. In W. K. Moorehead, ed. Etowah Papers. Department of Archaeology, Phillips Academy. Yale University Press. New Haven, Connecticut.

Prescott, William H.

1986 History of the Conquest of Mexico. University of Chicago Press. Chicago, Illinois.

2005 History of the Conquest of Peru. Dover Publications, Inc. Mineola, New York.

Priestly, Herbert I.

1928 The Luna Papers. The Florida State Historical Society. Deland, Florida.

Setzler, Frank M., and Jesse D. Jennings

1941 Peachtree Mound and Village Site, Cherokee County, North Carolina. Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, vol. 131. Washington, D. C.

Smith, Marvin T.

1989 Indian Responses to European Contact: The Coosa Example. In J. T. Milanich and S. Milbrath, eds. First Encounters. University Presses of Florida. Gainesville, Florida.

2000 Coosa: The Rise and Fall of a Southeastern Mississippian Chiefdom. University of Florida Press. Gainesville, Florida.