Death, Graves, and Cemeteries on the 1559 Luna Expedition, Including Aztec Burials

by David B. Dodson

Contact Archeology Inc.

ArcheologyInk.com: an Online Journal, April 2017

Where and What Might Be the Archeological Record?

During the Don Tristán de Luna settlement expedition to la Florida hundreds of settlers died, as did Spanish soldiers, Aztec warriors, and mariners, perhaps totaling over 400 souls. Some drowned aboard the ships during the hurricane of September 19-20, 1559, some by the arrows from the Indians, some by hunger or by eating poisonous plants and roots while starving up at Nanipacana, some by hanging for their crimes, and some also drowned when rafts overturned floating down the river towards Mobile Bay. The latter was part of the “bailout plan” to relocate the main settlement force from Nanipacana down to the known bay where they might survive on the maritime foodstuff of fish and shellfish. I believe the finding of cemeteries would be another “marker artifact” to discovering the original Luna settlement site in Pensacola and the second site at Santa Cruz de Nanipacana located somewhere up the lower Alabama River.

With this in mind, overall, there could have been at least five possible locations of cemeteries associated with the expedition. The first would be at Polonça, which is the name they soon gave the settlement at Pensacola; the second would be over on the Gulf Breeze peninsula where the bodies of drowned seamen from 1559 shipwrecks might have floated ashore from the north winds of the hurricane; the third—and by far the largest—would be at Nanapicana up in Alabama with the most-documented starvation and death; the fourth located somewhere along the banks of the Alabama River between Nanapicana and the delta of Mobile Bay where people drowned (Priestley II, 1928); and the fifth located near D’Olive Bayou at the delta on Mobile Bay where the expedition had traveled to survive on the abundant fish and shellfish. That site is archeologically known as 1Ba196.[1] Also, as to the possibility of a Spanish cemetery up at Coosa, we presently have no knowledge that anybody died on that reconnaissance expedition.

[1] For an updated report concerning the reinterpretation of the archaeological record, see A Camp Site of Tristan de Luna on Mobile Bay? at http://archeologyink.com/home/a-campsite-of-tristan-de-luna-on-mobile-bay/

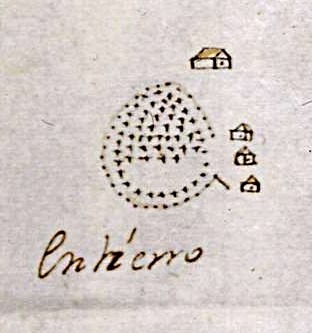

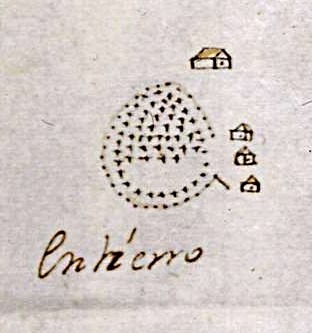

But, again, I believe the main or largest cemeteries will be found at Polonça (Pensacola) and at Santa Cruz de Nanipacana. Having investigated the type of churches the Spanish constructed on the Luna expedition, the graves would not have been within the church boundary or walls but in a cemetery located a reasonable distance away for sanitation purposes. This is how Spanish people were buried at the 1698 location of Pensacola, which was called Santa Maria de Galve. While that settlement had a church, it was very small—like the one described at Polonça—and could not have accommodated burials. Instead, they located that cemetery just outside the fortification walls to the east, laid out almost as an ellipse in the Baroque style (Fig. 1) (AGI. Mexico 93).

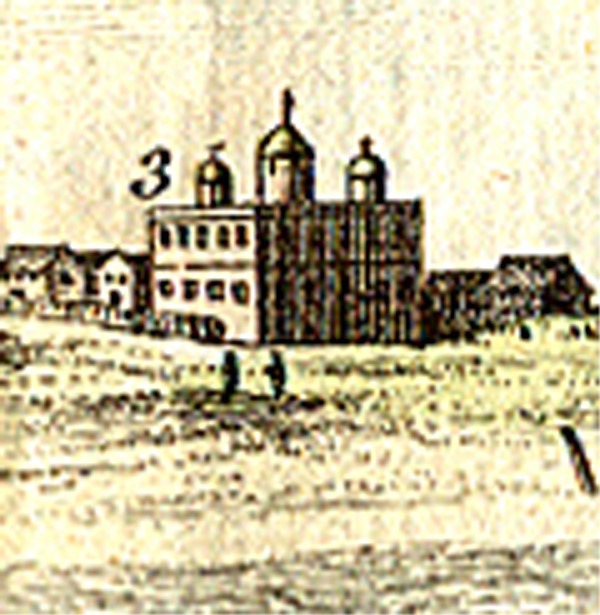

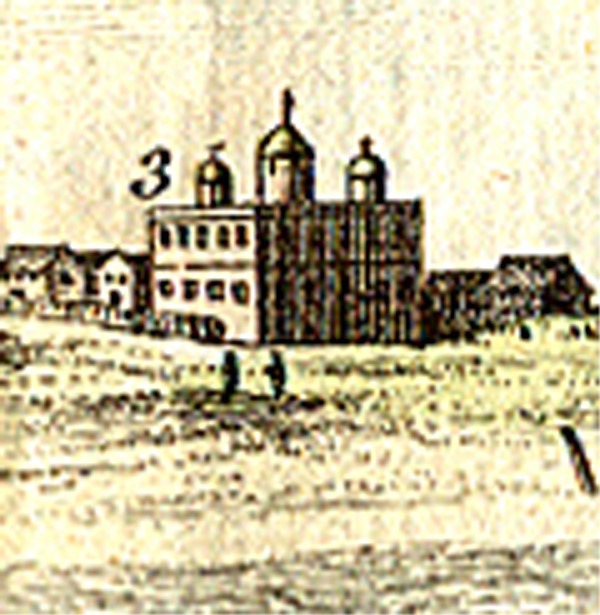

Conversely, the 1741-1752 settlement at Pensacola—located on Santa Rosa Island (Pensacola Beach)—had a very large church with a nave large enough to accommodate numerous, narrowly placed graves beneath the floor (Fig. 2) (Drawing by Dominic Serres, 1743).

We know this, because when the hurricane of 1752 struck, the treacherous waves and flooding waters damaged the church and bodies “floated out.” The official report from 1756 related:

The Church in the section of the north and northeast as a result of the force of the waves from the sea that battered it, had a part of the side broken down and a great portion of the floor of said church (gone) such that through the place that it broke through and swept away in said church, the bodies that were found buried in that place (came out) and we are persuaded that the bodies left through that place as was verified by having found a skull right outside the church when the wind died down (Childers, AGI. Mexico, 2448).

Thus, it was the size of the church (and place) that determined where and how the Spanish buried their dead.

Basically, death for a person of the Catholic Faith generally involved four main events; two worldly—obtaining the sacrament of The Last Rites and the physical act of dying; and two spiritual—atonement for their sins in a transitional place called Purgatory, and then the final entry into Heaven and everlasting life in the glory of God.

When a person knew they were close to dying (or had died), a priest would be sent for to perform the last ritual or sacrament known as The Last Rites. This typically included prayers of forgiveness, affirmation of Faith, and blessings for a good afterlife. Having this sacrament was extremely important to a Catholic whether they had lived a righteous or even a sinful life, for once your faith was pronounced and you were baptized one could eventually enter Heaven; but only after an appropriate stay of atonement and purification in a transitional place called Purgatory. In efforts to complete the path to Heaven, prayers from the living could shorten the time one spent in Purgatory. But sometimes monies were solicited by or given to the church in hopes of shortening a loved one’s stay. Upon the death of a young child or baby—referred to as the innocent—they would bypass Purgatory and go directly to Heaven.

Therefore, with all the calamity and avenues of dying by all ages of people on the Luna expedition, it was important for the soldiers and colonists to insure the good health and safety of the religious; and that was so well done that Viceroy Luis Velasco—recognizing that it was an old custom—advised Luna to withhold some of the provisions from the religious in order to conserve the food supplies for everyone (Priestley, 1928). It should be noted that all the original Dominican frays—except a lay brother who drowned in a shipwreck during the hurricane of September 1559—survived the expedition and lived relatively long lives, and some even into their eighties (O’Daniel, 1930).

With all this said, how did the Spanish actually bury their Christian brothers from 1559-1561 in the hinterlands of la Florida?

The known Luna documents do not give insight, but other burial sites excavated from the 16th century New World, especially in St. Augustine, which was settled only four years after Luna abandoned Pensacola Bay.

Archaeologists found that a body was typically wrapped in a shroud held together by a simple brass pin with the arms crossed over the chest. The bodies were interred in an east-facing orientation—in close burial spacing—in consecrated land sometimes inside the church or in an adjacent cemetery. The depth was most likely no more than five feet—just under the average height of a Spaniard-Mexican at that time—as to allow the excavators to actually get out of the dug grave without ladders. Coffins—nor their hardware—did not begin to show up until the English immigration of the late 18th century into Florida after Spain surrendered Florida in 1763 to the British (National Register Bulletin). While royalty in Spain had elaborate lead-lined coffins to hold in the miasmas or foul odor of a decaying corpse during elaborate funeral services—the commoner was only afforded a quick burial, usually interred in a simple shroud and naked as they came into this world as a baby. Also, if the graves were located in a cemetery, small wooden crosses would typically mark each grave. It is surmised that if the deceased were well liked or prominent, time would be taken to adorn the grave with a wooden marker or “tombstone” with their name etched into the wood; and if not, perhaps only a simple cross, even sans initials.

Therefore, since wooden crosses would have long rotted in the wet climate of la Florida, the search for a Spanish cemetery associated with the Luna expedition would be the hope to find concentrations of bones or teeth of the deceased. Sans actually finding graves via multiple test holes in a hit-or-miss methodology, the employment of ground-penetrating radar could discover the graves being identified as disturbances or “anomalies” within the underground landscape.

The present archeological record of the Gulf Coast has unearthed the skeletal remains of Natives in graves dating back well over 1,000 years in porous, sandy soils very similar to the soil types found in and around Pensacola Bay. Indeed, skeletal remains found in Native graves both on the Gulf Breeze peninsula and the mainland across the bay near the site of 1Ba196 in East Pensacola Heights date from the 1500s or even earlier. Skeletal remains in Native graves found in other less porous soils in today’s Alabama and Georgia have been dated as earlier as 3,000 years ago. Thus, it is very possible that archeologists could find skeletal remains that could identify the Spanish cemeteries associated with the Luna expedition.

Further, another artifact that would also assist in identifying a Spanish cemetery is the presence of a simple, straight brass pin. The pin was used to secure the burial shroud, which had been wrapped around the corpse. Such pins—even made of iron—have been found in colonial Spanish burials (as well as in English burials) in the New World in various shapes and sizes, including at St. Augustine ca. 1565 (Beaudry, 2006).

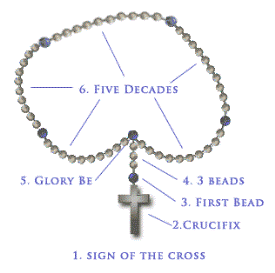

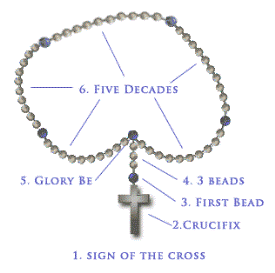

Also, as in the case of fray Bartolomé Metheos—the Dominican who drowned in the 1559 hurricane—perhaps even a cross on a chain or his rosary beads if they were indeed still found on the body after he drowned. The known love that other Dominicans had for the man and the horrible death he experienced might have induced them to inter such holy objects with his earthly remains. However, of all the graves excavated from the earliest Spanish period at St. Augustine, only one was found with rosary beads (Fig. 3).

Also, another artifact that could weather the test of time would be an amulet known by Spanish soldiers as a “figa” or a “mano fico.” Such amulets were generally quite small, carved from stone, and generally presented as a hand gesture or fist, and served as talismans to ward off evil spirits. A hole for a wire would be drilled at the base of the hand to attach the amulet to a necklace of sorts. Although figas were introduced into the Iberian Peninsula by the pagan Romans, the object was sometimes used by Christian soldiers as a “rabbits foot” for good luck. One figa—with the addition of its own “evil eye back”—was found in St. Augustine, Florida, in the area where the 1565 settlement was located (Fig. 4).

Aztec Burials

There were one hundred Aztecs nobles and their retinue from the four barrios of Mexico City and of El Tatebula that accompanied the soldiers and colonists on the Luna expedition (Priestley, 1928, Codice Osuna, 1565). These nobles were losing their influence in Mexico as the Spanish and the new government were replacing the pre-conquest life and stature their families once enjoyed. Therefore to secure favor and a reward from the Spanish government, they agreed to go along as warriors to augment the Spanish army. While they were in la Florida, the viceroy was supposed to make sure the family members of the volunteers were taken care of, but for whatever reason, this was not done (Codice Osuna 1565). But in any case, if you consider twenty-five nobles from each of the four barrios, with each group having at least five servants and the head noble one or two, their total population would amount to at least 135, and perhaps more. It is unclear in present documentation if these Indian soldiers were included in the overall number of soldiers—500 or so—or included in the overall expedition amount of 1,500 persons, which is generally noted in period letters and reports. But importantly, a lot of them died.

The evidence shows that the Aztecs were all Christians as the Viceroy would not have allowed “infidels” to accompany the soldiers and settlers. However, when it comes to death, old traditions are hard to give up, and it is possible that an Aztec burial in the wilds of la Florida would have been an amalgamation of Christian and Aztec burial rituals. And with this said, it is possible that the Aztecs might have been required—or chose to—bury their dead apart from the Spaniards.

Dominican fray Diego Duran—a first-hand observer of the native customs—recorded in his Historia de las Indias de Nueva-Espana y Islas de Tierra Firme, ca. 1580, of the many Aztec burial rituals. Duran noted that remains could be buried in fields or cemeteries, special shrines, in their yards, and even under the houses, as well as cremated with the remains stored in pots. Modern archaeologists have confirmed Duran’s observations and found that some of the dead were even buried dressed in their finest clothes and with pottery offering bowls; and others were indeed cremated and their remains stored in pots. I also believe that if an Aztec male were buried in “his finest clothes” he might have also have been buried with his obsidian or flint-bladed knife—another lasting artifact.

In AGI. Contaduria 877, it is recorded:

“Garcia Alonso, drover, was paid 28 pesos of the said common gold that he was owed for the contract for the rental of 14 mules that he brought loaded with the knight’s regalia of the Indian soldiers [perhaps of the jaguar and eagle knights?] that were going on the said voyage, from the pueblo of Xalapa to the said port of San Juan de Ulúa at an amount of 2 pesos of the said gold each which amounted to the said pesos as it appears by warrant of the said Alcalde Mayor dated on the 5th of the said month and his letter of payment before the notary (Childers, 1999).

Thus, as the records show, the Aztecs were allowed to bring their knight’s regalia on the expedition, and the transportation costs were paid for by the crown. Therefore, it seems possible that if any such Aztec knight died in the hinterlands of la Florida—so far away from their family and home—he might have been buried in such regalia. Also, in many of the depictions or glyphs of the knights of the Jaguar and Eagle, the Aztec warriors are holding obsidian- or flint-bladed knives in their hands and it is possible a deceased Aztec noble might have been buried with that very personal item.

By period records, it appears that Aztec burials could be found at the site of Nanipacana since that is where most of the people died.

In the Luna Papers, the closest mention to an Aztec dying or possibly dying is found into petitions the Indians presented to Luna up at Nanipacana—which, along with many others—eventually persuaded Luna to agree on June 22, 1560, to leave that settlement and go down the river on rafts to what is today’s Mobile Bay delta.

The first petition was signed by 21 Indians who appear to be the knights, since they use both their first and last names.

…Until now we have been sustaining ourselves with a few herbs which used to be found here, but now there are no more, nor can any be found within more than four leagues around about here nor can we obtain any corn or acorns in large or small quantity. So, in order that we may not perish here in greater number than those who have died or perished,[1] will you not, in the name of his royal Highness, be pleased to give us a ship so that we may go to New Spain that we may preserve our lives…” (Priestley, 1928).

The second refers to the Indian craftsmen and laborers and is signed by 10 who only signed their first names:

…that the great need of food in this camp is well known to you, but to us more than to anyone else, for we have nowhere to obtain it, wherefore we are enduring insufferable want, and we fear that we shall perish (Priestley, 1928).

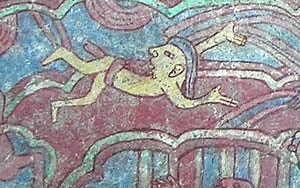

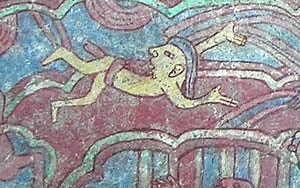

The Aztecs and the rest of the soldiers and settlers were therefore able to flee from the starvation at Nanipacana by floating on rafts down the river to the bay. But on that journey, many rafts were overturned and the people drowned. It is unknown if any of the Aztecs drowned in these fiascoes and were buried along the banks of the lower Alabama River, but one could reasonably assume—just like many of the Spanish settlers—that not all the Aztecs were adequate swimmers (Fig. 5).

[2] The line in Spanish reads, “porque no perezcamos mas de los que se an muerto y perecido…” A more accurate or simpler translation would be, “…because we do not more perish as those that have died and perished…” The latter, simpler translation gives better evidence that the Indian petitioners were specifically referring to preventing more Aztec Indian deaths.

Even one of the skillful mariners that the Viceroy Luis de Velasco had ordered to remain in la Florida after the hurricane to help erect the settlements (Priestley, 1928) could have easily been drawn under by the river currents, especially if they were weakened by starvation. Indeed, emaciated and sick women and children from an overturned raft would have had very little chance of survival especially if there were no husband to watch over them. By that timeline of the expedition, it was almost an “everyman for themselves”-type mentality.

Conclusion

When searching for the Luna settlements and encampments, evidence of a cemetery would be an excellent archeological marker, and we should at least be aware of the possibilities of perhaps “two cemeteries” within one; one area for the Christian soldiers and settlers, and one that might have the remains of “Christian” Aztecs perhaps even buried in all their regalia.

While all Christians are considered equal in the eyes of God, the separation of races and social classes in cemeteries—even Catholic ones—is an old practice that still lingers on today in some communities and nations. We therefore cannot assume all that died on the Luna expedition were buried in the same manner and location. Therefore, certain sections of a Luna-period cemetery might show discrimination concerning race, social class, or even as to age as would be with the children that died at Nanipacana. Burial practices and norms found in Mexico in 1559—even under the guidance of the Dominican frays—would have surely been carried to la Florida; for one cannot even imagine that any person of questionable reputation on the expedition would be allowed to sit in the front row of the church with Luna at a Mass, much less a soldier that was hung for mutinous or evil deeds to have a respectable or prominent burial site in a cemetery. Birth and its inherent status, life choices, and deeds certainly had an influence into the type of burials and their locations within a Christian cemetery.

Cemeteries therefore are a great archeological find. They will help pinpoint the two main settlements as well might reveal much about the social customs and status of the deceased. All cemeteries are hallowed ground, and as such, are to be investigated with the proper care and with the accompanying reverence.

Appendix One

A Sample of Excavated Human Remains on the Coasts of the Gulf and Atlantic as well as the Lower Alabama River

by: Caleb Curren Contact Archeology Inc.

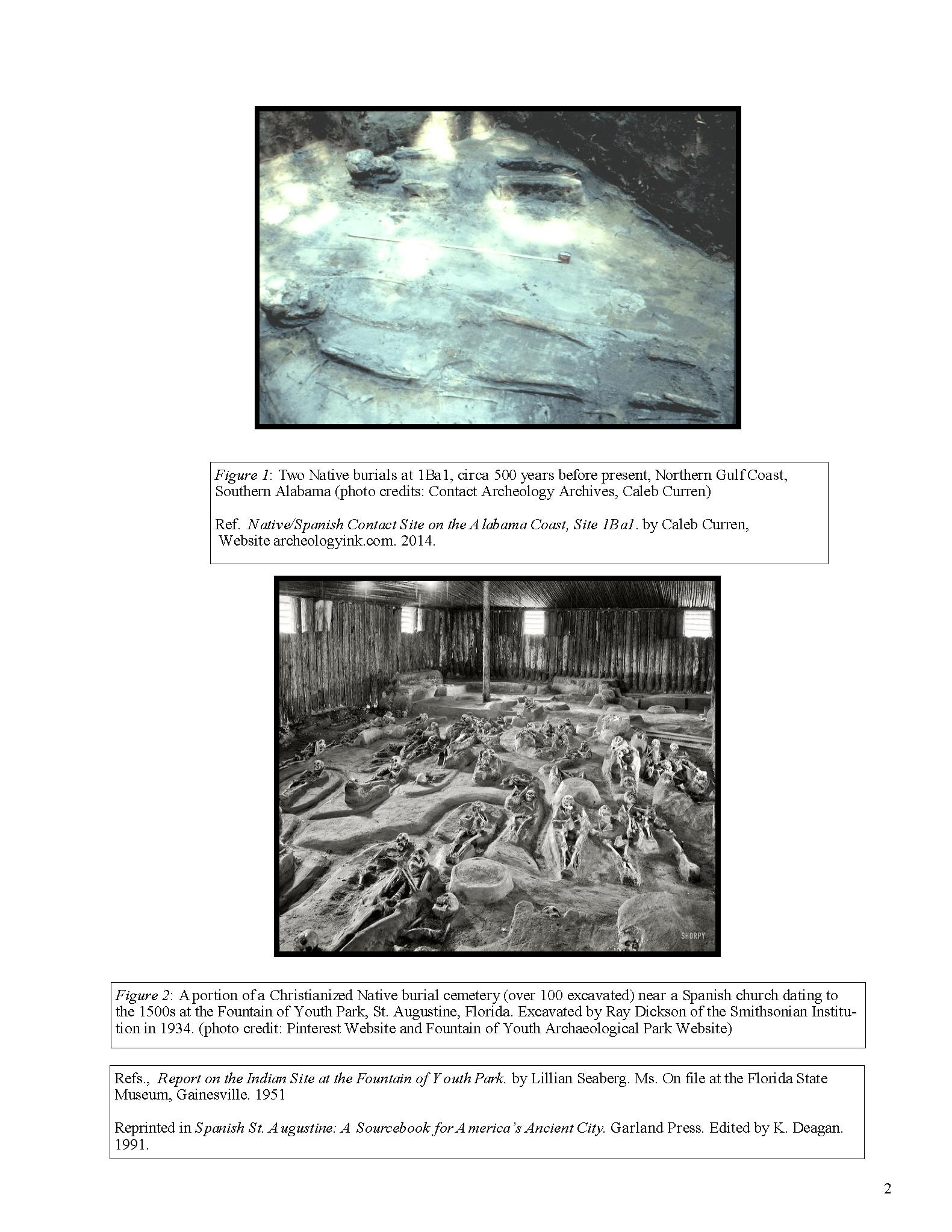

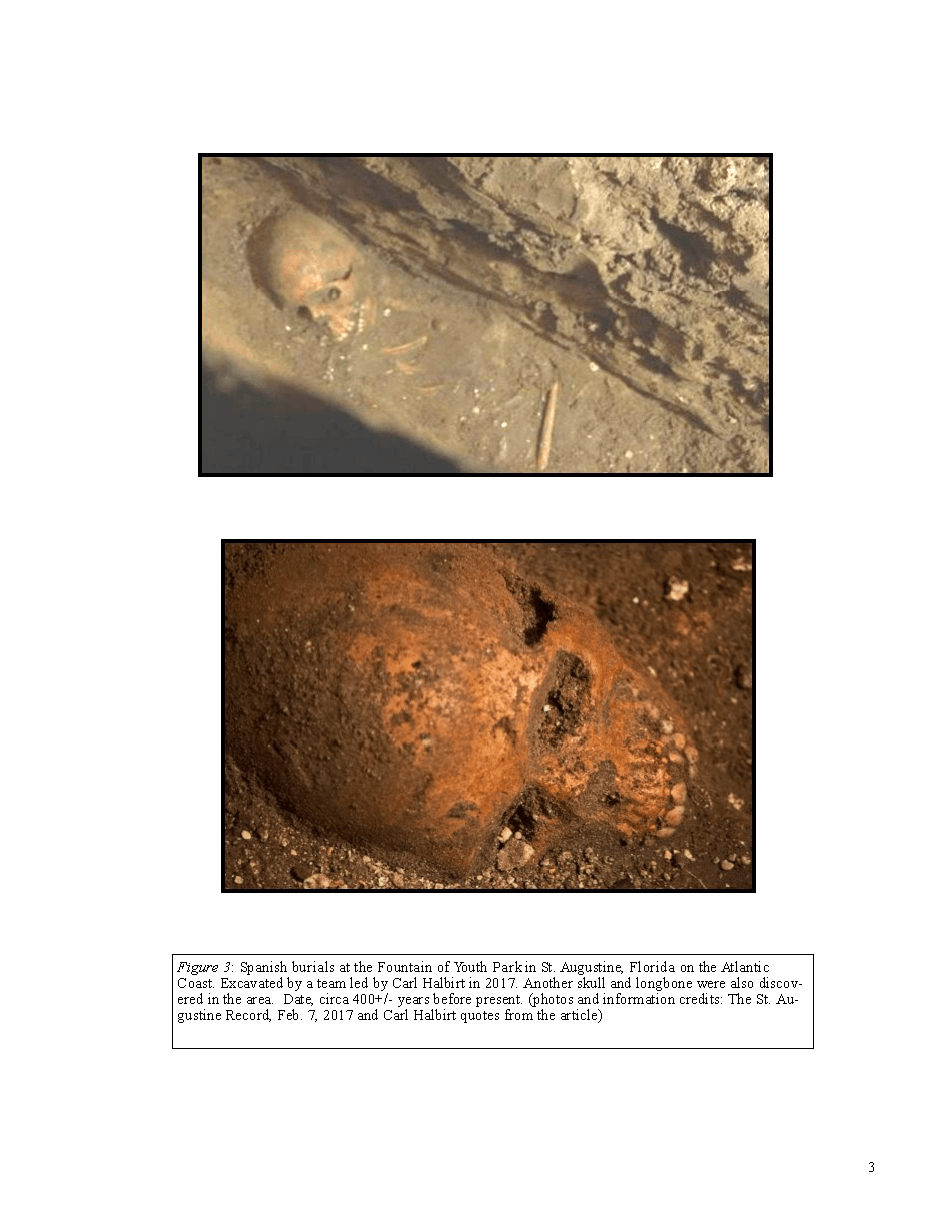

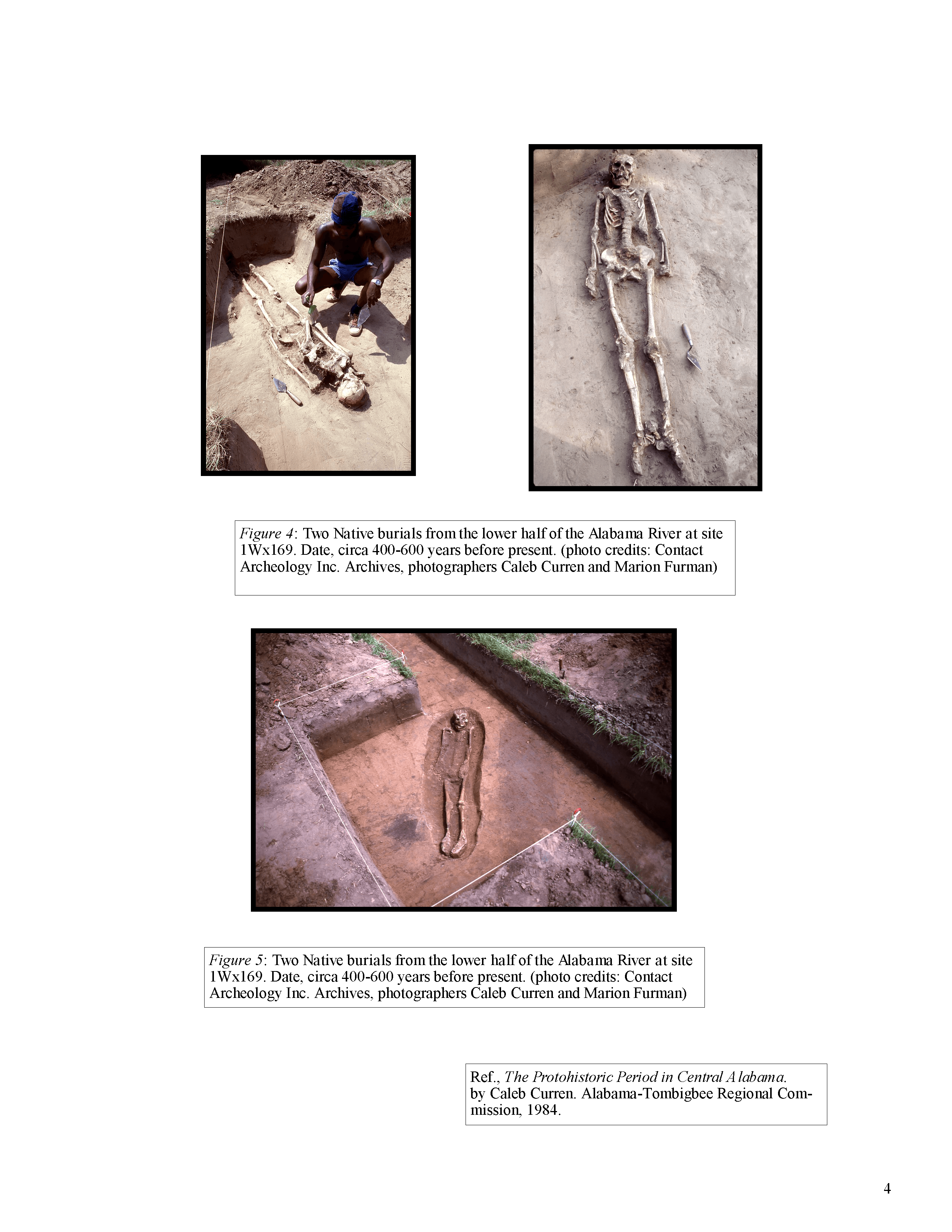

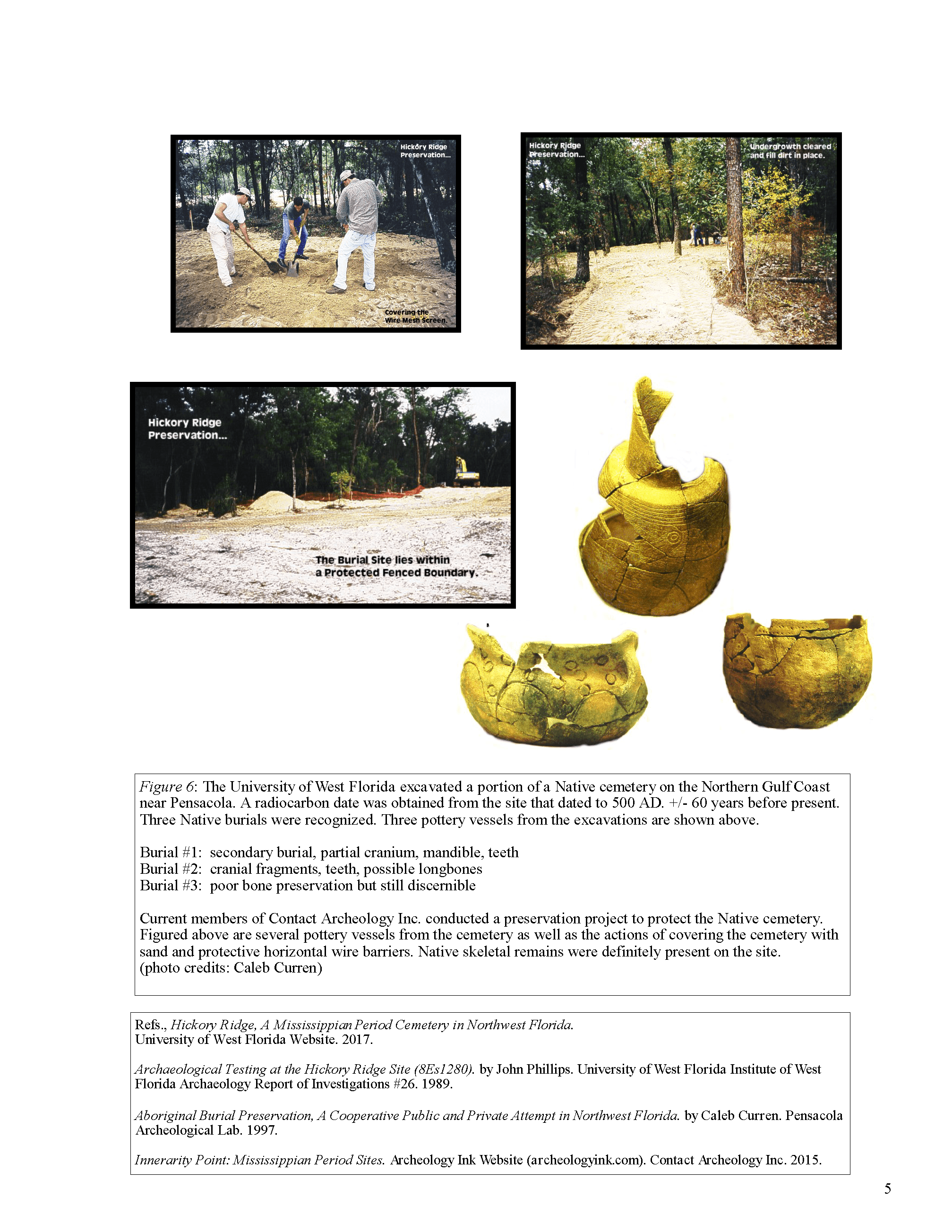

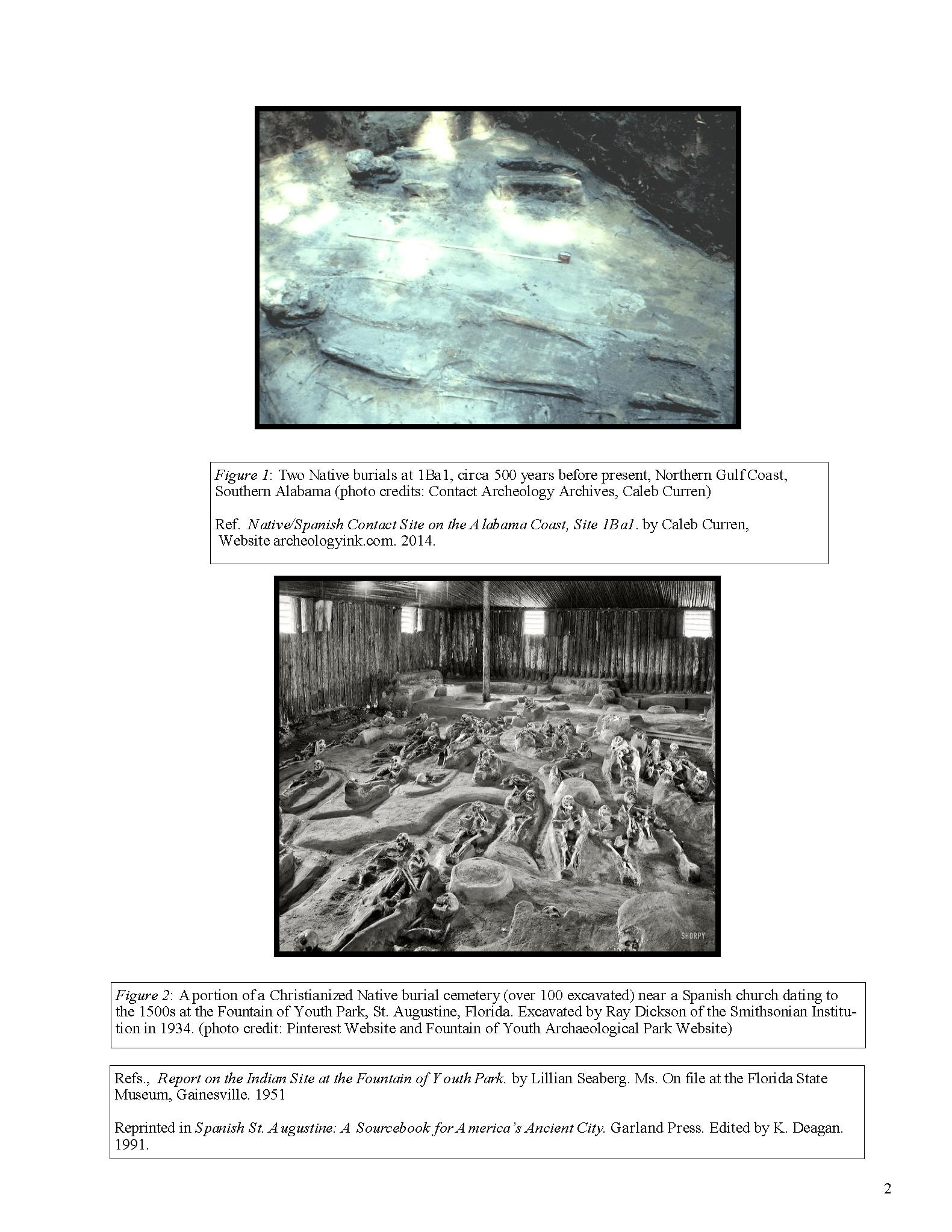

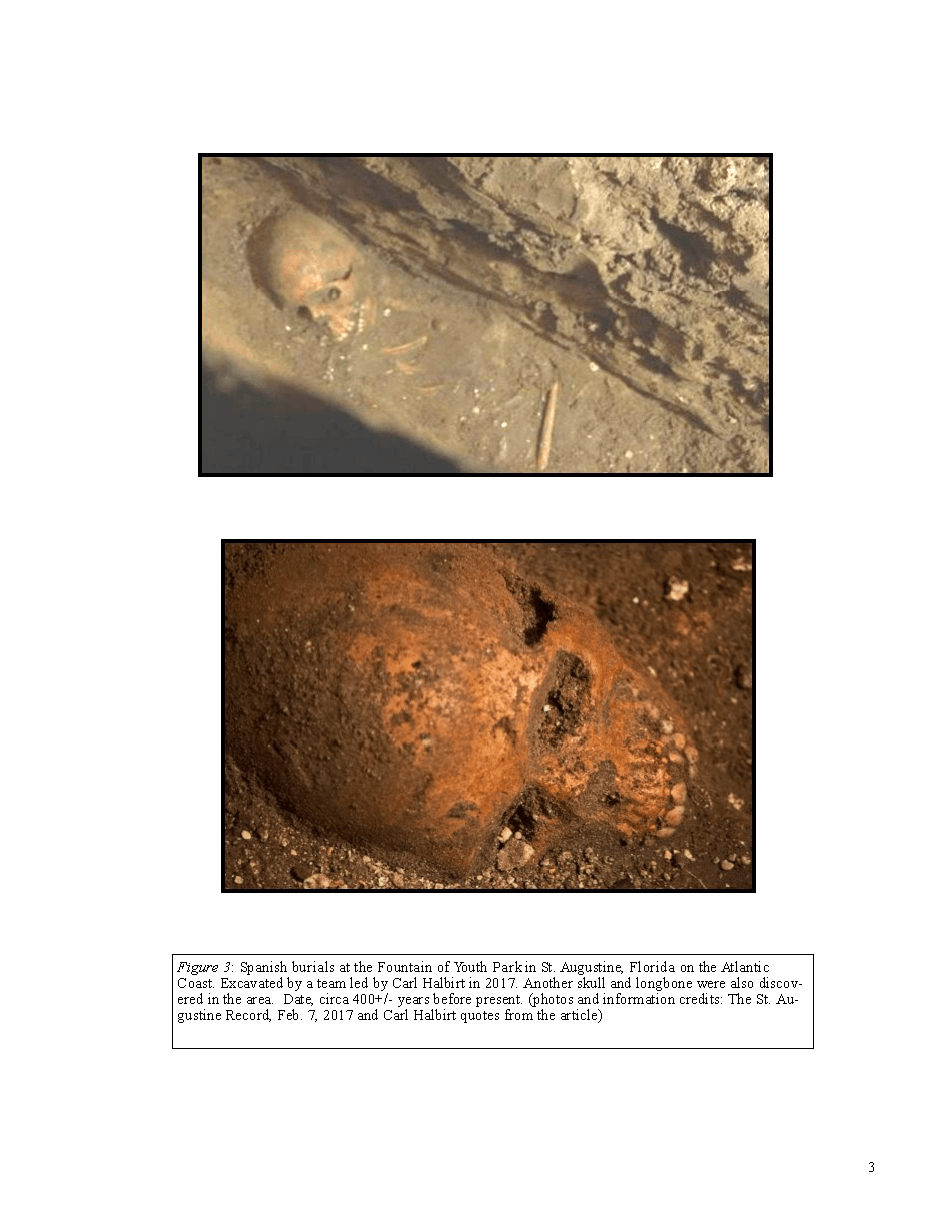

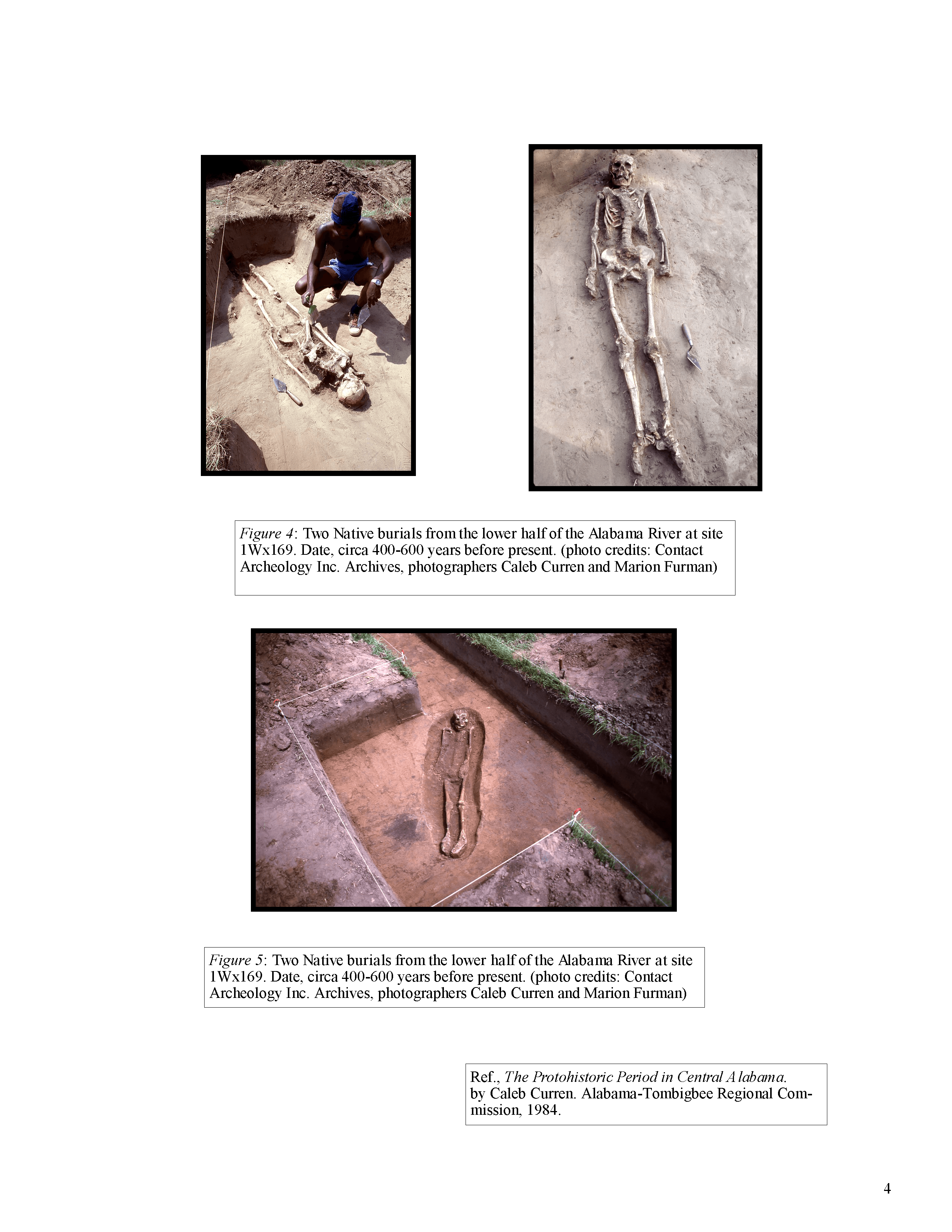

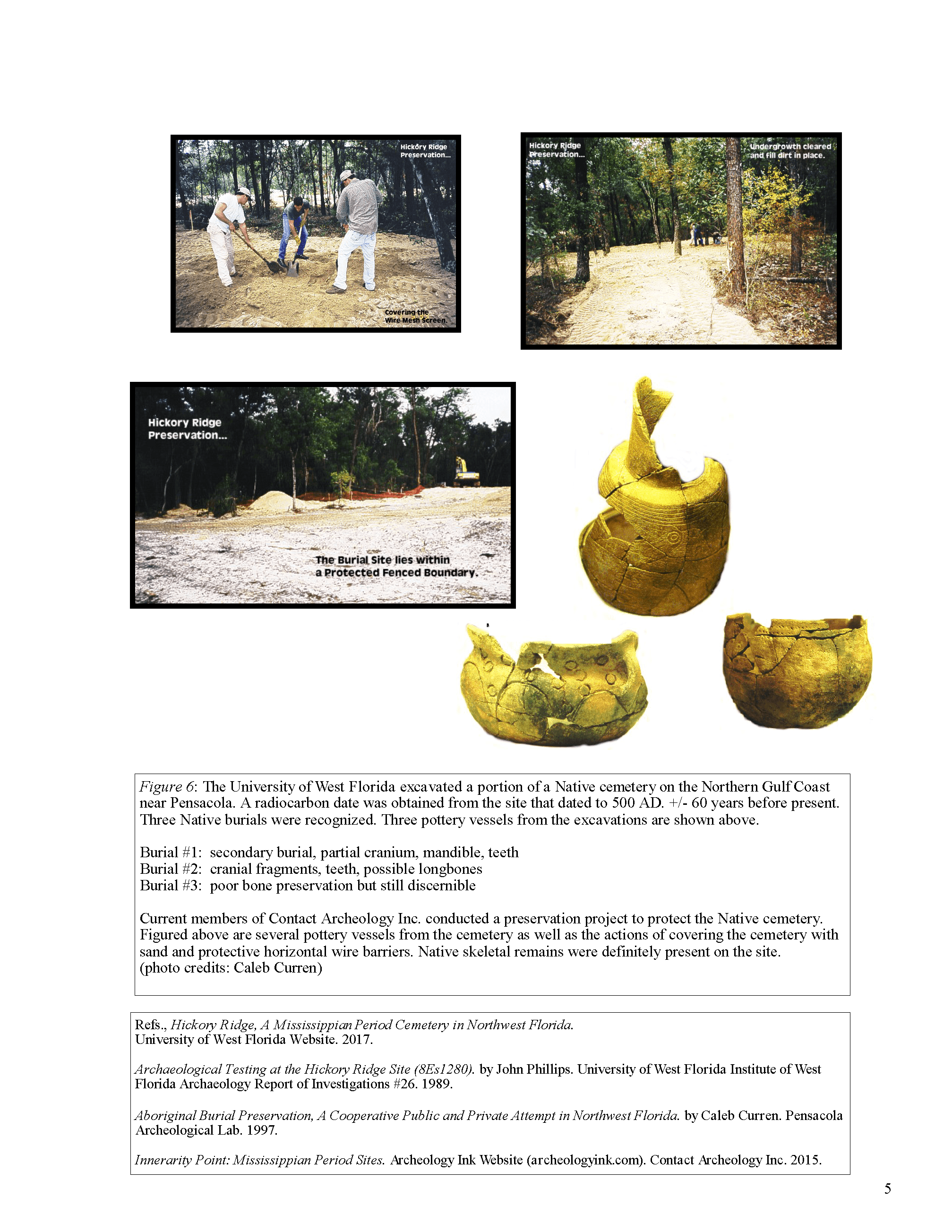

One major question concerning the discovery of the 1559 Spanish Luna settlements on Pensacola Bay and the Alabama River is … Might human skeletal remains from colonists who died on the expedition be found in the form of bones and teeth at the settlement sites located somewhere on the bay and the river? If so, those remains could be major evidence of the presence of the locations of the 16th-Century Spanish settlements.

That brings up the question of how long human remains of Spanish or Native burials might be preserved being buried in soils of the Pensacola Bay area and the inland area of the lower Alabama River?

Human remains have been excavated by archeologists on the northern Gulf Coast and the interior of Alabama since the late 1800s. The preservation factor relative to the bones and teeth of the human remains are reliant upon the pH acidity or alkalinity factors of the surrounding soils. If the soils are very acidic, the bones and teeth are dissolved at a more rapid rate. If the soils are more basic, the bones and teeth tend to be preserved for longer periods of time.

Human remains buried in midden deposits containing numerous marine or brackish water shellfish species are better preserved due to the neutralization of the surrounding acidic soils by the calcium carbonate content of the shells. However, human bone and teeth remains are also found in more acidic soils of the Gulf and Atlantic coasts even without the accumulation of shellfish remains surrounding them.

It is highly likely that human remains of the Luna Expedition on the Gulf Coast and inland areas will be arche- ologically recognizable, due in part to the relatively short period of their time buried underground (circa 400+ years). Furthermore, human skeletal remains dating to the 1500s have been excavated along the coasts and interior of Florida and Alabama for decades. The remains are mostly comprised of Native burials, but the preservation factor remains, be the burials Spanish or Native. Human bones are human bones regardless of their cultural origin.

The following figures provide samples of Native and Spanish burials dating to the period of approximately 400+ years before present. These data reinforce the high probability of identifiable skeletal remains of Spanish burials from the Luna settlements on Pensacola Bay and the Alabama River. As such, Spanish skeletal remains are absolute marker artifacts of a historic Spanish presence. Of all relevant diagnostic features indicative of the presence of early Spanish and Naïve contact sites, undoubtedly Spanish skeletal remains are the most diagnostic.

Sources

AGI. Mexico 93, Mapas y Planos, Santa Maria de Galve, 1699.

Beaudry, Mary Carolyn

Findings: The Material Culture of Needlework And Sewing, Yale University Press, 2006, 186.

Childers, R. Wayne

Translator, AGI Mexico 2448, Autos on the Hurricane of 1752, compiled in 1756.

Codice Osuna, ca. 1565. Facsimile Reproduction of this work edited in Madrid in 1878.

Coker, William S.

Pedro De Rivera’s Report on the Presidio of Punta De Siguenza, Alias Panzacola, 1744, January 1, 1975.

Deegan, Kathleen

HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY AT THE FOUNTAIN OF YOUTH PARK SITE (8SJ31) ST. AUGUSTINE, FLORIDA 1934-2007, 284, Final Report on Florida Bureau of Historical Resources Special Category Grant # SC 616 Draft 3 July 1, 2008, revised June 15, 2009.

Duran, Diego

Historia de las Indias de Nueva-Espana y Islas de Tierra Firme, 1581, a first hand observer of the native customs.

Hall, Martin, and Stephen W. Silliman

Editors, Historical Archaeology, Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford, UK, 2006, pages 260-263.

National Register Bulletin II

Burial Customs and Cemeteries in American History, http://www.nps.gov/nr/publications/bulletins/nrb41/nrb41_5.htm

O’Daniel, Very Reverend V.F.

Dominicans in Early Florida, The U.S. Catholic Historical Society, New York, 1930.

Padilla, Agustín Dávila

Historía de la Fundación y discorso de la provincia de Santiago de México de la orden de Predicadores, Pedro Madrigal, Madrid 1596; a second edition printed by Ivan (Juan) de Meerbeque, Brussles 1625.

Pre-Columbian Swimmer

From a wall painting at Teotihuacan, Mexico (ca. 500 AD), Carr, K.E. American Swimming. Quatr.us Study Guides, August 2016. Web. 20 April, 2017, http://quatr.us/games/americanswimming.htm

Priestley, Herbert Ingram

The Luna Papers, Florida State Historical Society, Deland, 1928.

Serres, Dominic

Perspective View of Pensacola, 1743, printed in the Universal Magazine, London, 1764.

United States Conference of Catholic Bishops

How To Pray The Rosary, http://www.usccb.org/prayer-and- worship/prayers-and-devotions/rosaries/how-to-pray-the-rosary.cfm

- Article

-

ArcheologyInk.com: an Online Journal, April 2017

Where and What Might Be the Archeological Record?

During the Don Tristán de Luna settlement expedition to la Florida hundreds of settlers died, as did Spanish soldiers, Aztec warriors, and mariners, perhaps totaling over 400 souls. Some drowned aboard the ships during the hurricane of September 19-20, 1559, some by the arrows from the Indians, some by hunger or by eating poisonous plants and roots while starving up at Nanipacana, some by hanging for their crimes, and some also drowned when rafts overturned floating down the river towards Mobile Bay. The latter was part of the “bailout plan” to relocate the main settlement force from Nanipacana down to the known bay where they might survive on the maritime foodstuff of fish and shellfish. I believe the finding of cemeteries would be another “marker artifact” to discovering the original Luna settlement site in Pensacola and the second site at Santa Cruz de Nanipacana located somewhere up the lower Alabama River.

With this in mind, overall, there could have been at least five possible locations of cemeteries associated with the expedition. The first would be at Polonça, which is the name they soon gave the settlement at Pensacola; the second would be over on the Gulf Breeze peninsula where the bodies of drowned seamen from 1559 shipwrecks might have floated ashore from the north winds of the hurricane; the third—and by far the largest—would be at Nanapicana up in Alabama with the most-documented starvation and death; the fourth located somewhere along the banks of the Alabama River between Nanapicana and the delta of Mobile Bay where people drowned (Priestley II, 1928); and the fifth located near D’Olive Bayou at the delta on Mobile Bay where the expedition had traveled to survive on the abundant fish and shellfish. That site is archeologically known as 1Ba196.[1] Also, as to the possibility of a Spanish cemetery up at Coosa, we presently have no knowledge that anybody died on that reconnaissance expedition.

[1] For an updated report concerning the reinterpretation of the archaeological record, see A Camp Site of Tristan de Luna on Mobile Bay? at http://archeologyink.com/home/a-campsite-of-tristan-de-luna-on-mobile-bay/

But, again, I believe the main or largest cemeteries will be found at Polonça (Pensacola) and at Santa Cruz de Nanipacana. Having investigated the type of churches the Spanish constructed on the Luna expedition, the graves would not have been within the church boundary or walls but in a cemetery located a reasonable distance away for sanitation purposes. This is how Spanish people were buried at the 1698 location of Pensacola, which was called Santa Maria de Galve. While that settlement had a church, it was very small—like the one described at Polonça—and could not have accommodated burials. Instead, they located that cemetery just outside the fortification walls to the east, laid out almost as an ellipse in the Baroque style (Fig. 1) (AGI. Mexico 93).

Figure 1. Cemetery at Santa Maria de Galve, 1699 Conversely, the 1741-1752 settlement at Pensacola—located on Santa Rosa Island (Pensacola Beach)—had a very large church with a nave large enough to accommodate numerous, narrowly placed graves beneath the floor (Fig. 2) (Drawing by Dominic Serres, 1743).

Figure 2. Church on Santa Rosa Island, 1743 We know this, because when the hurricane of 1752 struck, the treacherous waves and flooding waters damaged the church and bodies “floated out.” The official report from 1756 related:

The Church in the section of the north and northeast as a result of the force of the waves from the sea that battered it, had a part of the side broken down and a great portion of the floor of said church (gone) such that through the place that it broke through and swept away in said church, the bodies that were found buried in that place (came out) and we are persuaded that the bodies left through that place as was verified by having found a skull right outside the church when the wind died down (Childers, AGI. Mexico, 2448).

Thus, it was the size of the church (and place) that determined where and how the Spanish buried their dead.

Basically, death for a person of the Catholic Faith generally involved four main events; two worldly—obtaining the sacrament of The Last Rites and the physical act of dying; and two spiritual—atonement for their sins in a transitional place called Purgatory, and then the final entry into Heaven and everlasting life in the glory of God.

When a person knew they were close to dying (or had died), a priest would be sent for to perform the last ritual or sacrament known as The Last Rites. This typically included prayers of forgiveness, affirmation of Faith, and blessings for a good afterlife. Having this sacrament was extremely important to a Catholic whether they had lived a righteous or even a sinful life, for once your faith was pronounced and you were baptized one could eventually enter Heaven; but only after an appropriate stay of atonement and purification in a transitional place called Purgatory. In efforts to complete the path to Heaven, prayers from the living could shorten the time one spent in Purgatory. But sometimes monies were solicited by or given to the church in hopes of shortening a loved one’s stay. Upon the death of a young child or baby—referred to as the innocent—they would bypass Purgatory and go directly to Heaven.

Therefore, with all the calamity and avenues of dying by all ages of people on the Luna expedition, it was important for the soldiers and colonists to insure the good health and safety of the religious; and that was so well done that Viceroy Luis Velasco—recognizing that it was an old custom—advised Luna to withhold some of the provisions from the religious in order to conserve the food supplies for everyone (Priestley, 1928). It should be noted that all the original Dominican frays—except a lay brother who drowned in a shipwreck during the hurricane of September 1559—survived the expedition and lived relatively long lives, and some even into their eighties (O’Daniel, 1930).

With all this said, how did the Spanish actually bury their Christian brothers from 1559-1561 in the hinterlands of la Florida?

The known Luna documents do not give insight, but other burial sites excavated from the 16th century New World, especially in St. Augustine, which was settled only four years after Luna abandoned Pensacola Bay.

Archaeologists found that a body was typically wrapped in a shroud held together by a simple brass pin with the arms crossed over the chest. The bodies were interred in an east-facing orientation—in close burial spacing—in consecrated land sometimes inside the church or in an adjacent cemetery. The depth was most likely no more than five feet—just under the average height of a Spaniard-Mexican at that time—as to allow the excavators to actually get out of the dug grave without ladders. Coffins—nor their hardware—did not begin to show up until the English immigration of the late 18th century into Florida after Spain surrendered Florida in 1763 to the British (National Register Bulletin). While royalty in Spain had elaborate lead-lined coffins to hold in the miasmas or foul odor of a decaying corpse during elaborate funeral services—the commoner was only afforded a quick burial, usually interred in a simple shroud and naked as they came into this world as a baby. Also, if the graves were located in a cemetery, small wooden crosses would typically mark each grave. It is surmised that if the deceased were well liked or prominent, time would be taken to adorn the grave with a wooden marker or “tombstone” with their name etched into the wood; and if not, perhaps only a simple cross, even sans initials.

Therefore, since wooden crosses would have long rotted in the wet climate of la Florida, the search for a Spanish cemetery associated with the Luna expedition would be the hope to find concentrations of bones or teeth of the deceased. Sans actually finding graves via multiple test holes in a hit-or-miss methodology, the employment of ground-penetrating radar could discover the graves being identified as disturbances or “anomalies” within the underground landscape.

The present archeological record of the Gulf Coast has unearthed the skeletal remains of Natives in graves dating back well over 1,000 years in porous, sandy soils very similar to the soil types found in and around Pensacola Bay. Indeed, skeletal remains found in Native graves both on the Gulf Breeze peninsula and the mainland across the bay near the site of 1Ba196 in East Pensacola Heights date from the 1500s or even earlier. Skeletal remains in Native graves found in other less porous soils in today’s Alabama and Georgia have been dated as earlier as 3,000 years ago. Thus, it is very possible that archeologists could find skeletal remains that could identify the Spanish cemeteries associated with the Luna expedition.

Further, another artifact that would also assist in identifying a Spanish cemetery is the presence of a simple, straight brass pin. The pin was used to secure the burial shroud, which had been wrapped around the corpse. Such pins—even made of iron—have been found in colonial Spanish burials (as well as in English burials) in the New World in various shapes and sizes, including at St. Augustine ca. 1565 (Beaudry, 2006).

Also, as in the case of fray Bartolomé Metheos—the Dominican who drowned in the 1559 hurricane—perhaps even a cross on a chain or his rosary beads if they were indeed still found on the body after he drowned. The known love that other Dominicans had for the man and the horrible death he experienced might have induced them to inter such holy objects with his earthly remains. However, of all the graves excavated from the earliest Spanish period at St. Augustine, only one was found with rosary beads (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Rosary Beads worn around the neck, or wrapped around one’s wrist Also, another artifact that could weather the test of time would be an amulet known by Spanish soldiers as a “figa” or a “mano fico.” Such amulets were generally quite small, carved from stone, and generally presented as a hand gesture or fist, and served as talismans to ward off evil spirits. A hole for a wire would be drilled at the base of the hand to attach the amulet to a necklace of sorts. Although figas were introduced into the Iberian Peninsula by the pagan Romans, the object was sometimes used by Christian soldiers as a “rabbits foot” for good luck. One figa—with the addition of its own “evil eye back”—was found in St. Augustine, Florida, in the area where the 1565 settlement was located (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Figa, Back and Frontal Views Aztec Burials

There were one hundred Aztecs nobles and their retinue from the four barrios of Mexico City and of El Tatebula that accompanied the soldiers and colonists on the Luna expedition (Priestley, 1928, Codice Osuna, 1565). These nobles were losing their influence in Mexico as the Spanish and the new government were replacing the pre-conquest life and stature their families once enjoyed. Therefore to secure favor and a reward from the Spanish government, they agreed to go along as warriors to augment the Spanish army. While they were in la Florida, the viceroy was supposed to make sure the family members of the volunteers were taken care of, but for whatever reason, this was not done (Codice Osuna 1565). But in any case, if you consider twenty-five nobles from each of the four barrios, with each group having at least five servants and the head noble one or two, their total population would amount to at least 135, and perhaps more. It is unclear in present documentation if these Indian soldiers were included in the overall number of soldiers—500 or so—or included in the overall expedition amount of 1,500 persons, which is generally noted in period letters and reports. But importantly, a lot of them died.

The evidence shows that the Aztecs were all Christians as the Viceroy would not have allowed “infidels” to accompany the soldiers and settlers. However, when it comes to death, old traditions are hard to give up, and it is possible that an Aztec burial in the wilds of la Florida would have been an amalgamation of Christian and Aztec burial rituals. And with this said, it is possible that the Aztecs might have been required—or chose to—bury their dead apart from the Spaniards.

Dominican fray Diego Duran—a first-hand observer of the native customs—recorded in his Historia de las Indias de Nueva-Espana y Islas de Tierra Firme, ca. 1580, of the many Aztec burial rituals. Duran noted that remains could be buried in fields or cemeteries, special shrines, in their yards, and even under the houses, as well as cremated with the remains stored in pots. Modern archaeologists have confirmed Duran’s observations and found that some of the dead were even buried dressed in their finest clothes and with pottery offering bowls; and others were indeed cremated and their remains stored in pots. I also believe that if an Aztec male were buried in “his finest clothes” he might have also have been buried with his obsidian or flint-bladed knife—another lasting artifact.

In AGI. Contaduria 877, it is recorded:

“Garcia Alonso, drover, was paid 28 pesos of the said common gold that he was owed for the contract for the rental of 14 mules that he brought loaded with the knight’s regalia of the Indian soldiers [perhaps of the jaguar and eagle knights?] that were going on the said voyage, from the pueblo of Xalapa to the said port of San Juan de Ulúa at an amount of 2 pesos of the said gold each which amounted to the said pesos as it appears by warrant of the said Alcalde Mayor dated on the 5th of the said month and his letter of payment before the notary (Childers, 1999).

Thus, as the records show, the Aztecs were allowed to bring their knight’s regalia on the expedition, and the transportation costs were paid for by the crown. Therefore, it seems possible that if any such Aztec knight died in the hinterlands of la Florida—so far away from their family and home—he might have been buried in such regalia. Also, in many of the depictions or glyphs of the knights of the Jaguar and Eagle, the Aztec warriors are holding obsidian- or flint-bladed knives in their hands and it is possible a deceased Aztec noble might have been buried with that very personal item.

By period records, it appears that Aztec burials could be found at the site of Nanipacana since that is where most of the people died.

In the Luna Papers, the closest mention to an Aztec dying or possibly dying is found into petitions the Indians presented to Luna up at Nanipacana—which, along with many others—eventually persuaded Luna to agree on June 22, 1560, to leave that settlement and go down the river on rafts to what is today’s Mobile Bay delta.

The first petition was signed by 21 Indians who appear to be the knights, since they use both their first and last names.

…Until now we have been sustaining ourselves with a few herbs which used to be found here, but now there are no more, nor can any be found within more than four leagues around about here nor can we obtain any corn or acorns in large or small quantity. So, in order that we may not perish here in greater number than those who have died or perished,[1] will you not, in the name of his royal Highness, be pleased to give us a ship so that we may go to New Spain that we may preserve our lives…” (Priestley, 1928).

The second refers to the Indian craftsmen and laborers and is signed by 10 who only signed their first names:

…that the great need of food in this camp is well known to you, but to us more than to anyone else, for we have nowhere to obtain it, wherefore we are enduring insufferable want, and we fear that we shall perish (Priestley, 1928).

The Aztecs and the rest of the soldiers and settlers were therefore able to flee from the starvation at Nanipacana by floating on rafts down the river to the bay. But on that journey, many rafts were overturned and the people drowned. It is unknown if any of the Aztecs drowned in these fiascoes and were buried along the banks of the lower Alabama River, but one could reasonably assume—just like many of the Spanish settlers—that not all the Aztecs were adequate swimmers (Fig. 5).

[2] The line in Spanish reads, “porque no perezcamos mas de los que se an muerto y perecido…” A more accurate or simpler translation would be, “…because we do not more perish as those that have died and perished…” The latter, simpler translation gives better evidence that the Indian petitioners were specifically referring to preventing more Aztec Indian deaths.

Figure 5. Pre-Columbian Native Swimmer in Mexico (ca. 500 A.D.) Even one of the skillful mariners that the Viceroy Luis de Velasco had ordered to remain in la Florida after the hurricane to help erect the settlements (Priestley, 1928) could have easily been drawn under by the river currents, especially if they were weakened by starvation. Indeed, emaciated and sick women and children from an overturned raft would have had very little chance of survival especially if there were no husband to watch over them. By that timeline of the expedition, it was almost an “everyman for themselves”-type mentality.

Conclusion

When searching for the Luna settlements and encampments, evidence of a cemetery would be an excellent archeological marker, and we should at least be aware of the possibilities of perhaps “two cemeteries” within one; one area for the Christian soldiers and settlers, and one that might have the remains of “Christian” Aztecs perhaps even buried in all their regalia.

While all Christians are considered equal in the eyes of God, the separation of races and social classes in cemeteries—even Catholic ones—is an old practice that still lingers on today in some communities and nations. We therefore cannot assume all that died on the Luna expedition were buried in the same manner and location. Therefore, certain sections of a Luna-period cemetery might show discrimination concerning race, social class, or even as to age as would be with the children that died at Nanipacana. Burial practices and norms found in Mexico in 1559—even under the guidance of the Dominican frays—would have surely been carried to la Florida; for one cannot even imagine that any person of questionable reputation on the expedition would be allowed to sit in the front row of the church with Luna at a Mass, much less a soldier that was hung for mutinous or evil deeds to have a respectable or prominent burial site in a cemetery. Birth and its inherent status, life choices, and deeds certainly had an influence into the type of burials and their locations within a Christian cemetery.

Cemeteries therefore are a great archeological find. They will help pinpoint the two main settlements as well might reveal much about the social customs and status of the deceased. All cemeteries are hallowed ground, and as such, are to be investigated with the proper care and with the accompanying reverence.

Appendix One

A Sample of Excavated Human Remains on the Coasts of the Gulf and Atlantic as well as the Lower Alabama River

by: Caleb Curren Contact Archeology Inc.

One major question concerning the discovery of the 1559 Spanish Luna settlements on Pensacola Bay and the Alabama River is … Might human skeletal remains from colonists who died on the expedition be found in the form of bones and teeth at the settlement sites located somewhere on the bay and the river? If so, those remains could be major evidence of the presence of the locations of the 16th-Century Spanish settlements.

That brings up the question of how long human remains of Spanish or Native burials might be preserved being buried in soils of the Pensacola Bay area and the inland area of the lower Alabama River?

Human remains have been excavated by archeologists on the northern Gulf Coast and the interior of Alabama since the late 1800s. The preservation factor relative to the bones and teeth of the human remains are reliant upon the pH acidity or alkalinity factors of the surrounding soils. If the soils are very acidic, the bones and teeth are dissolved at a more rapid rate. If the soils are more basic, the bones and teeth tend to be preserved for longer periods of time.

Human remains buried in midden deposits containing numerous marine or brackish water shellfish species are better preserved due to the neutralization of the surrounding acidic soils by the calcium carbonate content of the shells. However, human bone and teeth remains are also found in more acidic soils of the Gulf and Atlantic coasts even without the accumulation of shellfish remains surrounding them.

It is highly likely that human remains of the Luna Expedition on the Gulf Coast and inland areas will be arche- ologically recognizable, due in part to the relatively short period of their time buried underground (circa 400+ years). Furthermore, human skeletal remains dating to the 1500s have been excavated along the coasts and interior of Florida and Alabama for decades. The remains are mostly comprised of Native burials, but the preservation factor remains, be the burials Spanish or Native. Human bones are human bones regardless of their cultural origin.

The following figures provide samples of Native and Spanish burials dating to the period of approximately 400+ years before present. These data reinforce the high probability of identifiable skeletal remains of Spanish burials from the Luna settlements on Pensacola Bay and the Alabama River. As such, Spanish skeletal remains are absolute marker artifacts of a historic Spanish presence. Of all relevant diagnostic features indicative of the presence of early Spanish and Naïve contact sites, undoubtedly Spanish skeletal remains are the most diagnostic.

- References and Related Works

-

Sources

AGI. Mexico 93, Mapas y Planos, Santa Maria de Galve, 1699.

Beaudry, Mary Carolyn

Findings: The Material Culture of Needlework And Sewing, Yale University Press, 2006, 186.

Childers, R. Wayne

Translator, AGI Mexico 2448, Autos on the Hurricane of 1752, compiled in 1756.

Codice Osuna, ca. 1565. Facsimile Reproduction of this work edited in Madrid in 1878.

Coker, William S.

Pedro De Rivera’s Report on the Presidio of Punta De Siguenza, Alias Panzacola, 1744, January 1, 1975.

Deegan, Kathleen

HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY AT THE FOUNTAIN OF YOUTH PARK SITE (8SJ31) ST. AUGUSTINE, FLORIDA 1934-2007, 284, Final Report on Florida Bureau of Historical Resources Special Category Grant # SC 616 Draft 3 July 1, 2008, revised June 15, 2009.

Duran, Diego

Historia de las Indias de Nueva-Espana y Islas de Tierra Firme, 1581, a first hand observer of the native customs.

Hall, Martin, and Stephen W. Silliman

Editors, Historical Archaeology, Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford, UK, 2006, pages 260-263.

National Register Bulletin II

Burial Customs and Cemeteries in American History, http://www.nps.gov/nr/publications/bulletins/nrb41/nrb41_5.htm

O’Daniel, Very Reverend V.F.

Dominicans in Early Florida, The U.S. Catholic Historical Society, New York, 1930.

Padilla, Agustín Dávila

Historía de la Fundación y discorso de la provincia de Santiago de México de la orden de Predicadores, Pedro Madrigal, Madrid 1596; a second edition printed by Ivan (Juan) de Meerbeque, Brussles 1625.

Pre-Columbian Swimmer

From a wall painting at Teotihuacan, Mexico (ca. 500 AD), Carr, K.E. American Swimming. Quatr.us Study Guides, August 2016. Web. 20 April, 2017, http://quatr.us/games/americanswimming.htm

Priestley, Herbert Ingram

The Luna Papers, Florida State Historical Society, Deland, 1928.

Serres, Dominic

Perspective View of Pensacola, 1743, printed in the Universal Magazine, London, 1764.

United States Conference of Catholic Bishops

How To Pray The Rosary, http://www.usccb.org/prayer-and- worship/prayers-and-devotions/rosaries/how-to-pray-the-rosary.cfm

- Download PDF Version