Anchorage or Grounding?

Two Shipwrecks of the 1559 Luna Expedition, Pensacola Bay, Florida

by Caleb Curren

Contact Archeology Ink

A 16th-Century shipwreck was discovered in Pensacola Bay in the autumn of 1992 by archeologists from the Florida Bureau of Archeological Research. Another Spanish shipwreck was found in the summer of 2006 by the University of West Florida. Both shipwrecks were found off Pensacola near the northern shore of the bay. The shipwrecks were part of an 11-ship fleet of a 1559 Spanish colonization expedition launched from Vera Cruz, Mexico, with Pensacola Bay as its destination. The fleet was at anchor in Pensacola Bay when a hurricane hit (Priestley 1928; Smith 2009; Smith et al. 1995, 1998; Davila Padilla 1596).

“There came up a great tempest from the north, which, blowing for twenty-four hours from all directions … did irreparable damage to the ships of the fleet. … All the ships which were in this port went aground … save only one caravel and two barks, which escaped.” (Priestley 1928: vol. II, pg. 245). It was “the most terrible storm and wildest norther that men have ever seen.” (It was) “as if the (anchor) cables were threads of string and the anchors were not iron, the force of the wind destroyed them. It tore loose the ships and broke them into little pieces” (Davila Padilla 1596: pg. 236).

All but three ships of the fleet in the anchorage were lost. Two of the causalities included the two Pensacola Bay shipwrecks that were driven aground on a shallow sand shelf by the winds and waves of the storm. Once grounded, the ships were broken apart by the storm. Stone ballast piles and portions of the lower hulls remain on the bottom of Pensacola Bay today. “The (Pensacola Bay) ship apparently had grounded violently during a severe storm on a shallow sand bar …” (Smith 2009: pg. 79).

Some of the ships were separated from their anchorage area by the storm and driven aground in areas around the bay. Some may have sunk at anchor. Some broke their anchor lines as stated in the Spanish documents of the expedition (Priestley 1928: vol. II, pg. 245) (Davila 1596). Some may have dragged their anchors for a distance before the anchor lines severed under the strain and the ships were grounded.

So where was the original anchorage of the 10-ship fleet (one returned to Vera Cruz before the storm) remaining in Pensacola Bay as should be evidenced by a considerable number of anchors left on the bay bottom? If the 10 lost ships carried 7 anchors each, the total anchor-grouping would be around 70 anchors. A total of 7 anchors were found on the 1554 Spanish shipwreck in coastal, south Texas (Arnold and Weddle, 1978: pg. 224). Obviously, the smaller vessels of the 1559 Luna fleet would carry fewer anchors than the larger vessels but the hypothesis is valid … There is likely an impressive grouping of anchors from the Luna fleet somewhere on the bottom of Pensacola Bay adjacent to the Luna Colony. Such a grouping of 16th-Century anchors has not, to date, been located near the two Pensacola Bay shipwrecks adjacent to the alleged Luna Colony site at 8Es1.

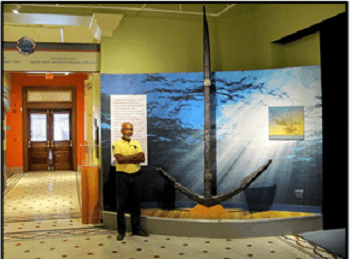

Only one anchor (fig. 1, previous page) was found at the sites of the two Pensacola shipwrecks (Smith et al. 1995, 1998; Cook 2009; per. com. John Bratten, 1/4/15). It was found near the starboard bow of one of the shipwrecks. That anchor position is thought to be evidence that it was lashed to the side (gunwale) of the ship. Lashing several anchors of various types on each side of a ship was an accepted practice during the 1500s (Smith et al. 1998: pg. 76). The anchor very well might not have been in use when the ship was grounded.

Where are the multiple anchors certainly carried by the two Pensacola Bay shipwrecks? Might the anchors have been salvaged after the hurricane by Spanish or Native divers? The Spanish Viceroy in Mexico did give orders to salvage anchors and use them as moorings to reestablish an anchorage after the hurricane but were his orders carried out by the hard-pressed hurricane survivors (Priestley 1928: vol. I, pg. 73)? Even if the Viceroy’s orders were obeyed, it seems logical that the salvaged anchors would have been reset in a relatively close grouping, perhaps even at the original anchorage.

There is a precedent for shipwreck salvage in the 1500s on the northern Gulf Coast. Three Spanish ships were grounded in the shallows off Padre Island in south Texas in 1554. The ships were part of a four-ship treasure fleet bound for Spain from the Vera Cruz area of Mexico. The fleet ran into a hurricane. The Padre Island ships were driven across the Gulf of Mexico until they grounded on the shallow sands of the island. One of the ships was excavated by archeologists from Texas A&M University. The ship was underway, not anchored, when the hurricane struck, therefore, it held a large complement of anchors on board when grounded in the shallows. The anchors went down with the ship (Arnold and Weddle, 1978: pgs. 224-230).

Seven anchors were found directly associated with the Padre Island shipwreck. Two more anchors were found nearby, possibly associated with another of the three shipwrecks. The nine anchors were not retrieved by the 1554 Spanish salvors from Mexico who arrived on the scene approximately two months after the groundings (Arnold and Weddle, 1978: pgs. 130-144 and 224-230). Might that 16th-Century Padre Island salvage procedure be applicable to the Pensacola Bay shipwrecks?

It seems reasonable that the anchors of the Pensacola Bay shipwrecks were left at the colony anchorage when the ships’ anchor lines broke during the storm. Might the anchors of the fleet be nearby the two Pensacola Bay shipwrecks, perhaps in deeper water? That may be unlikely, due to the nature of the waters at the shipwreck sites. That area of the bay is exposed to weather from three directions with only the mainland to the north as protection.

The underwater archeology program at the University of West Florida has conducted highly respected research for decades. Concerning the two shipwrecks, the University has stated: “While the locations of these two vessels in the same vicinity may suggest that others lie nearby, it still cannot be determined if the ships were blown to this location by the hurricane, or grounded near their anchorage.” (Cook 2009: pg. 98). University of West Florida underwater archeologists plan on intensifying their search for other shipwrecks and/or anchors in the general area of the two known grounded shipwrecks (John Bratten, personal communication, 1/4/15).

The recent claim by the University that the Luna Colony has definitely been found at a large Native village site, 8Es1, is based partially on the two 16th-Century shipwrecks discovered just offshore from the Native village. It is a virtual certainty that the two shipwrecks were part of the 1559 Spanish fleet. However, it is not a certainty that the shipwrecks provide indisputable evidence of the University’s claim that 8Es1 is the main Luna Colony site.

As detailed previously in this article, the two shipwrecks were grounded by the storm that scattered the Spanish fleet. The ships were not sunk at anchor nor has an anchorage been found in the area of the two shipwrecks, thus negating the inference by the University that the two shipwrecks support their conclusion that the Native village of 8Es1 is the Luna Colony location. The Native village at 8Es1 may yet prove to be the location of the Luna Colony but currently the presence of the two grounded shipwrecks should not be used as undisputed evidence that site 8Es1 equates to the colony site.

In addition, it is reasonable to rely on the writings of members of the 1559 Spanish Luna expedition to aid researchers in the discovery of the actual location of the colony:

“The (colony) site … is a high point of land which slopes down to the bay where the ships come to anchor.” and “The ships can anchor in four or five fathoms (approx. 20-25 feet in 1559) a crossbow shot from land.” (Priestley 1928: vol. II, pgs. 211 and 275). The maximum distance of a 16th-Century crossbow shot when elevated 45 degrees is approximately 380 yards (Payne-Gallwey 1958: pg. 20). The approximate distance from site 8Es1 to the two grounded Luna shipwrecks is 1000-1500 yards. It is clear that the two shipwrecks were not at anchor, therefore, the original anchorage would have been even farther away from the alleged Luna Colony site.

Maybe the authors of the Luna Colony letters were mistaken with their distance estimates from the shore to the fleet … or maybe they weren’t. Maybe British Sir Ralph Payne-Gallwey was inaccurate with his crossbow range based on his field trials … or maybe he wasn’t.

The archeological footprint of the 1559 terrestrial Luna Colony is reconstructable based on the historical and archeological record. The archeological site is located on a “high” point which slopes down to the Pensacola Bay shore. Logically, the site has a nearby freshwater source. The site area has enough flat ground to allow for the building of the colony site as blueprinted by the King of Spain and the Viceroy of Mexico. The site contains 16th-Century Spanish artifacts and subsurface features such as fire hearths, Spanish burials, and perhaps refuse pits and postholes related to structures. There is a 16th-Century fleet anchorage in Pensacola Bay approximately 380 yards off the terrestrial colony. These criteria are necessary archeological requisites to definitively demonstrate the location of the main Luna Colony site.

Thus far, archeological features such as those noted above have not been found at 8Es1. Neither has a cluster of anchors and/or other shipwrecks indicative of the Luna fleet been found in the bay adjacent to site 8Es1.

Sixteenth-Century Spanish artifacts have indeed been found at site 8Es1. Pottery sherds have been the primary artifact class recovered during recent excavations by the University of West Florida (John Worth, Elizabeth Benchley, Tom Garner, personal communications, Nov.-Dec. 2015; Pensacola News Journal: 12/18/15, 12/20/15, and 12/20/15). This Spanish pottery frequency was also found to be the case during the excavations of Contact Archeology members beginning in the early 1990s while developing and testing hypotheses relative to the Luna Colony location in areas of Pensacola Bay (Curren 1994; Pensacola News Journal, 6/13/90 and 7/16/93; Tallahassee Democrat, 9/19/93; Little and Curren 1990: pgs. 169-195; Curren et al. 1989: pgs. 381-389). Members of the current Contact Archeology organization decided in those past years that it was prudent to be patient, continue testing the subject sites including 8Es1, and determine if the Luna Colony criteria of necessary artifacts and features were recovered before issuing any public claims.

Tom Garner, a local historian, recently found a concentration of several classes of 16th-Century Spanish artifacts on the surface in a relative small area of the larger 8Es1 site in October of 2015. Included in the collection were European glass trade beads, several types of Spanish pottery sherds, several sherds of Aztec pottery, and small metal items. Native pottery sherds were also among the artifact concentration. The University of West Florida considers this artifact concentration to be a part of the general Luna Colony artifact assemblage associated with site 8Es1 (Elizabeth Benchley, personal communication, 12/19/15). However, the unusually varied Spanish artifact concentration could, conversely, be trade goods buried in one of two burial mounds reported on site 8Es1 during an 1883 Smithsonian expedition to the site and noted during another Smithsonian expedition to the site in 1947 (Walker 1883: pg. 855; Willey 1949: pg. 200).

The recent claim by the University of West Florida that site 8Es1 is the main Luna Colony may eventually be proven to be legitimate (Pensacola News Journal: 12/18/15, 12/20/15, and 12/20/15). However, as it currently stands, it is the opinion of Contact Archeology Inc. that more archeological data are needed both on land and underwater to legitimize such an emphatic Luna Colony claim by the University.

So, if 8Es1 is not the main Luna Colony site what are the alternatives? A Spanish salvors camp based at the Native village of 8Es1? Native spoils brought back to their village from salvaging objects from the two shipwrecks? An offshoot of the main Luna Colony located elsewhere? Or is 8Es1 really the main Luna Colony as claimed by the University of West Florida? Time and excavation will tell.

The University is continuing their excavations at site 8Es1. Underwater surveys and excavations at and near the shipwreck sites are also underway. Hopefully, the appropriate terrestrial and marine features necessary to validate the University’s 8Es1 Luna Colony claim will be found in the near future.

Contact Archeology Inc. is continuing test excavations in other areas on the northern mainland adjacent to Pensacola Bay in search of Luna Colony site candidates and/or related sites. It is truly an educational, interesting, and exciting time in the exploration of Pensacola’s early history.

References Cited:

Arnold, J. Barto III and Robert Weddle

1978 The Nautical Archaeology of Padre Island: The Spanish Shipwrecks of 1554. Academic Press, New York.

Cook, Gregory D.

2009 Luna’s Ships: Current Excavations on Emanuel Point II and Preliminary Comparisons with the First Emanuel Point Ship wreck. The Florida Anthropologist Vol. 62, Nos. 3-4.

Curren, Caleb

1994 The Search for Santa Maria, a 1559 Spanish Colony on the Northern Florida Coast. Pensacola

Archeology Lab.

Curren, Caleb, Keith J. Little, and Harry O. Holstein

1989 Aboriginal Societies Encountered by the Tristan de Luna Expedition. The Florida Anthropologist

Vol. 42, No. 4.

Little, Keith J. and Caleb Curren

1990 Conquest Archaeology of Alabama. Columbian Consequences: Archaeological and Historical

Perspectives on the Spanish Borderlands East. (ed.) David Hurst Thomas. Smithsonian Institution Press.

Newspaper Articles:

1990 Coin dates to the days of Luna. Pensacola News Journal: 6/13/90

1993 On the trail of Luna. Pensacola News Journal: 7/16/93

1993 Scientist searches for the first European colony. Tallahassee Democrat: 9/19/93

2015 We found Luna’s colony. Pensacola News Journal: 12/18/15

2015 Luna Colony found, the search is over. Pensacola News Journal: 12/17/15

2015 Don Tristan de Luna settlement historic discovery. Pensacola News Journal: 12/20/15

2015 It’s a crowning achievement for UWF president. Pensacola News Journal: 12/20/15

Padilla, Fray Agustin Davila

1596 Historia de la Fundacion y discorso de la provincial de Santiago de Mexico de la ordende Predicadores.

Madrid. (Chapters 51-71, The Florida Expeditions).

Payne-Gallwey, Sir Ralph

1958 The Crossbow. Bramhall House, New York.

Priestley, Herbert I.

1928 The Luna Papers. Publications of the Florida State historical Society No. 8: vols. I-II. Deland, Florida.

Smith, Roger C.

2009 Luna’s Fleet and the Discovery of the Discovery of the First Emanuel Point Shipwreck. The Florida

Anthropologist Vol. 62, Nos. 3-4.

Smith, Roger, James Spirek, John Bratten, Della Scott-Ireton.

1995 The Emanuel Point Ship: Archaeological Investigation, 1992-1995. Florida Department of State, Division of Historical Resources, Bureau of Historical Research, Tallahassee.

Smith, Roger C., John R. Bratten, J. Cozzi, and Keith Plaskett

1998 The Emanuel Point Ship: Archaeological Investigation, 1997-1998. Report of Investigations #68,

Archaeology Institute, University of West Florida, Pensacola.

Walker, S.T.

1883 Mounds and Shell Heaps on the West Coast of Florida. Smithsonian Annual Report.

- Article

-

A 16th-Century shipwreck was discovered in Pensacola Bay in the autumn of 1992 by archeologists from the Florida Bureau of Archeological Research. Another Spanish shipwreck was found in the summer of 2006 by the University of West Florida. Both shipwrecks were found off Pensacola near the northern shore of the bay. The shipwrecks were part of an 11-ship fleet of a 1559 Spanish colonization expedition launched from Vera Cruz, Mexico, with Pensacola Bay as its destination. The fleet was at anchor in Pensacola Bay when a hurricane hit (Priestley 1928; Smith 2009; Smith et al. 1995, 1998; Davila Padilla 1596).

“There came up a great tempest from the north, which, blowing for twenty-four hours from all directions … did irreparable damage to the ships of the fleet. … All the ships which were in this port went aground … save only one caravel and two barks, which escaped.” (Priestley 1928: vol. II, pg. 245). It was “the most terrible storm and wildest norther that men have ever seen.” (It was) “as if the (anchor) cables were threads of string and the anchors were not iron, the force of the wind destroyed them. It tore loose the ships and broke them into little pieces” (Davila Padilla 1596: pg. 236).

All but three ships of the fleet in the anchorage were lost. Two of the causalities included the two Pensacola Bay shipwrecks that were driven aground on a shallow sand shelf by the winds and waves of the storm. Once grounded, the ships were broken apart by the storm. Stone ballast piles and portions of the lower hulls remain on the bottom of Pensacola Bay today. “The (Pensacola Bay) ship apparently had grounded violently during a severe storm on a shallow sand bar …” (Smith 2009: pg. 79).

Some of the ships were separated from their anchorage area by the storm and driven aground in areas around the bay. Some may have sunk at anchor. Some broke their anchor lines as stated in the Spanish documents of the expedition (Priestley 1928: vol. II, pg. 245) (Davila 1596). Some may have dragged their anchors for a distance before the anchor lines severed under the strain and the ships were grounded.

So where was the original anchorage of the 10-ship fleet (one returned to Vera Cruz before the storm) remaining in Pensacola Bay as should be evidenced by a considerable number of anchors left on the bay bottom? If the 10 lost ships carried 7 anchors each, the total anchor-grouping would be around 70 anchors. A total of 7 anchors were found on the 1554 Spanish shipwreck in coastal, south Texas (Arnold and Weddle, 1978: pg. 224). Obviously, the smaller vessels of the 1559 Luna fleet would carry fewer anchors than the larger vessels but the hypothesis is valid … There is likely an impressive grouping of anchors from the Luna fleet somewhere on the bottom of Pensacola Bay adjacent to the Luna Colony. Such a grouping of 16th-Century anchors has not, to date, been located near the two Pensacola Bay shipwrecks adjacent to the alleged Luna Colony site at 8Es1.

Only one anchor (fig. 1, previous page) was found at the sites of the two Pensacola shipwrecks (Smith et al. 1995, 1998; Cook 2009; per. com. John Bratten, 1/4/15). It was found near the starboard bow of one of the shipwrecks. That anchor position is thought to be evidence that it was lashed to the side (gunwale) of the ship. Lashing several anchors of various types on each side of a ship was an accepted practice during the 1500s (Smith et al. 1998: pg. 76). The anchor very well might not have been in use when the ship was grounded.

Where are the multiple anchors certainly carried by the two Pensacola Bay shipwrecks? Might the anchors have been salvaged after the hurricane by Spanish or Native divers? The Spanish Viceroy in Mexico did give orders to salvage anchors and use them as moorings to reestablish an anchorage after the hurricane but were his orders carried out by the hard-pressed hurricane survivors (Priestley 1928: vol. I, pg. 73)? Even if the Viceroy’s orders were obeyed, it seems logical that the salvaged anchors would have been reset in a relatively close grouping, perhaps even at the original anchorage.

There is a precedent for shipwreck salvage in the 1500s on the northern Gulf Coast. Three Spanish ships were grounded in the shallows off Padre Island in south Texas in 1554. The ships were part of a four-ship treasure fleet bound for Spain from the Vera Cruz area of Mexico. The fleet ran into a hurricane. The Padre Island ships were driven across the Gulf of Mexico until they grounded on the shallow sands of the island. One of the ships was excavated by archeologists from Texas A&M University. The ship was underway, not anchored, when the hurricane struck, therefore, it held a large complement of anchors on board when grounded in the shallows. The anchors went down with the ship (Arnold and Weddle, 1978: pgs. 224-230).

Seven anchors were found directly associated with the Padre Island shipwreck. Two more anchors were found nearby, possibly associated with another of the three shipwrecks. The nine anchors were not retrieved by the 1554 Spanish salvors from Mexico who arrived on the scene approximately two months after the groundings (Arnold and Weddle, 1978: pgs. 130-144 and 224-230). Might that 16th-Century Padre Island salvage procedure be applicable to the Pensacola Bay shipwrecks?

It seems reasonable that the anchors of the Pensacola Bay shipwrecks were left at the colony anchorage when the ships’ anchor lines broke during the storm. Might the anchors of the fleet be nearby the two Pensacola Bay shipwrecks, perhaps in deeper water? That may be unlikely, due to the nature of the waters at the shipwreck sites. That area of the bay is exposed to weather from three directions with only the mainland to the north as protection.

The underwater archeology program at the University of West Florida has conducted highly respected research for decades. Concerning the two shipwrecks, the University has stated: “While the locations of these two vessels in the same vicinity may suggest that others lie nearby, it still cannot be determined if the ships were blown to this location by the hurricane, or grounded near their anchorage.” (Cook 2009: pg. 98). University of West Florida underwater archeologists plan on intensifying their search for other shipwrecks and/or anchors in the general area of the two known grounded shipwrecks (John Bratten, personal communication, 1/4/15).

The recent claim by the University that the Luna Colony has definitely been found at a large Native village site, 8Es1, is based partially on the two 16th-Century shipwrecks discovered just offshore from the Native village. It is a virtual certainty that the two shipwrecks were part of the 1559 Spanish fleet. However, it is not a certainty that the shipwrecks provide indisputable evidence of the University’s claim that 8Es1 is the main Luna Colony site.

As detailed previously in this article, the two shipwrecks were grounded by the storm that scattered the Spanish fleet. The ships were not sunk at anchor nor has an anchorage been found in the area of the two shipwrecks, thus negating the inference by the University that the two shipwrecks support their conclusion that the Native village of 8Es1 is the Luna Colony location. The Native village at 8Es1 may yet prove to be the location of the Luna Colony but currently the presence of the two grounded shipwrecks should not be used as undisputed evidence that site 8Es1 equates to the colony site.

In addition, it is reasonable to rely on the writings of members of the 1559 Spanish Luna expedition to aid researchers in the discovery of the actual location of the colony:

“The (colony) site … is a high point of land which slopes down to the bay where the ships come to anchor.” and “The ships can anchor in four or five fathoms (approx. 20-25 feet in 1559) a crossbow shot from land.” (Priestley 1928: vol. II, pgs. 211 and 275). The maximum distance of a 16th-Century crossbow shot when elevated 45 degrees is approximately 380 yards (Payne-Gallwey 1958: pg. 20). The approximate distance from site 8Es1 to the two grounded Luna shipwrecks is 1000-1500 yards. It is clear that the two shipwrecks were not at anchor, therefore, the original anchorage would have been even farther away from the alleged Luna Colony site.Maybe the authors of the Luna Colony letters were mistaken with their distance estimates from the shore to the fleet … or maybe they weren’t. Maybe British Sir Ralph Payne-Gallwey was inaccurate with his crossbow range based on his field trials … or maybe he wasn’t.

The archeological footprint of the 1559 terrestrial Luna Colony is reconstructable based on the historical and archeological record. The archeological site is located on a “high” point which slopes down to the Pensacola Bay shore. Logically, the site has a nearby freshwater source. The site area has enough flat ground to allow for the building of the colony site as blueprinted by the King of Spain and the Viceroy of Mexico. The site contains 16th-Century Spanish artifacts and subsurface features such as fire hearths, Spanish burials, and perhaps refuse pits and postholes related to structures. There is a 16th-Century fleet anchorage in Pensacola Bay approximately 380 yards off the terrestrial colony. These criteria are necessary archeological requisites to definitively demonstrate the location of the main Luna Colony site.

Thus far, archeological features such as those noted above have not been found at 8Es1. Neither has a cluster of anchors and/or other shipwrecks indicative of the Luna fleet been found in the bay adjacent to site 8Es1.

Sixteenth-Century Spanish artifacts have indeed been found at site 8Es1. Pottery sherds have been the primary artifact class recovered during recent excavations by the University of West Florida (John Worth, Elizabeth Benchley, Tom Garner, personal communications, Nov.-Dec. 2015; Pensacola News Journal: 12/18/15, 12/20/15, and 12/20/15). This Spanish pottery frequency was also found to be the case during the excavations of Contact Archeology members beginning in the early 1990s while developing and testing hypotheses relative to the Luna Colony location in areas of Pensacola Bay (Curren 1994; Pensacola News Journal, 6/13/90 and 7/16/93; Tallahassee Democrat, 9/19/93; Little and Curren 1990: pgs. 169-195; Curren et al. 1989: pgs. 381-389). Members of the current Contact Archeology organization decided in those past years that it was prudent to be patient, continue testing the subject sites including 8Es1, and determine if the Luna Colony criteria of necessary artifacts and features were recovered before issuing any public claims.

Tom Garner, a local historian, recently found a concentration of several classes of 16th-Century Spanish artifacts on the surface in a relative small area of the larger 8Es1 site in October of 2015. Included in the collection were European glass trade beads, several types of Spanish pottery sherds, several sherds of Aztec pottery, and small metal items. Native pottery sherds were also among the artifact concentration. The University of West Florida considers this artifact concentration to be a part of the general Luna Colony artifact assemblage associated with site 8Es1 (Elizabeth Benchley, personal communication, 12/19/15). However, the unusually varied Spanish artifact concentration could, conversely, be trade goods buried in one of two burial mounds reported on site 8Es1 during an 1883 Smithsonian expedition to the site and noted during another Smithsonian expedition to the site in 1947 (Walker 1883: pg. 855; Willey 1949: pg. 200).

The recent claim by the University of West Florida that site 8Es1 is the main Luna Colony may eventually be proven to be legitimate (Pensacola News Journal: 12/18/15, 12/20/15, and 12/20/15). However, as it currently stands, it is the opinion of Contact Archeology Inc. that more archeological data are needed both on land and underwater to legitimize such an emphatic Luna Colony claim by the University.

So, if 8Es1 is not the main Luna Colony site what are the alternatives? A Spanish salvors camp based at the Native village of 8Es1? Native spoils brought back to their village from salvaging objects from the two shipwrecks? An offshoot of the main Luna Colony located elsewhere? Or is 8Es1 really the main Luna Colony as claimed by the University of West Florida? Time and excavation will tell.

The University is continuing their excavations at site 8Es1. Underwater surveys and excavations at and near the shipwreck sites are also underway. Hopefully, the appropriate terrestrial and marine features necessary to validate the University’s 8Es1 Luna Colony claim will be found in the near future.

Contact Archeology Inc. is continuing test excavations in other areas on the northern mainland adjacent to Pensacola Bay in search of Luna Colony site candidates and/or related sites. It is truly an educational, interesting, and exciting time in the exploration of Pensacola’s early history.

- References Cited

-

References Cited:

Arnold, J. Barto III and Robert Weddle

1978 The Nautical Archaeology of Padre Island: The Spanish Shipwrecks of 1554. Academic Press, New York.Cook, Gregory D.

2009 Luna’s Ships: Current Excavations on Emanuel Point II and Preliminary Comparisons with the First Emanuel Point Ship wreck. The Florida Anthropologist Vol. 62, Nos. 3-4.Curren, Caleb

1994 The Search for Santa Maria, a 1559 Spanish Colony on the Northern Florida Coast. Pensacola

Archeology Lab.Curren, Caleb, Keith J. Little, and Harry O. Holstein

1989 Aboriginal Societies Encountered by the Tristan de Luna Expedition. The Florida Anthropologist

Vol. 42, No. 4.Little, Keith J. and Caleb Curren

1990 Conquest Archaeology of Alabama. Columbian Consequences: Archaeological and Historical

Perspectives on the Spanish Borderlands East. (ed.) David Hurst Thomas. Smithsonian Institution Press.Newspaper Articles:

1990 Coin dates to the days of Luna. Pensacola News Journal: 6/13/90

1993 On the trail of Luna. Pensacola News Journal: 7/16/93

1993 Scientist searches for the first European colony. Tallahassee Democrat: 9/19/93

2015 We found Luna’s colony. Pensacola News Journal: 12/18/15

2015 Luna Colony found, the search is over. Pensacola News Journal: 12/17/15

2015 Don Tristan de Luna settlement historic discovery. Pensacola News Journal: 12/20/15

2015 It’s a crowning achievement for UWF president. Pensacola News Journal: 12/20/15Padilla, Fray Agustin Davila

1596 Historia de la Fundacion y discorso de la provincial de Santiago de Mexico de la ordende Predicadores.

Madrid. (Chapters 51-71, The Florida Expeditions).Payne-Gallwey, Sir Ralph

1958 The Crossbow. Bramhall House, New York.Priestley, Herbert I.

1928 The Luna Papers. Publications of the Florida State historical Society No. 8: vols. I-II. Deland, Florida.Smith, Roger C.

2009 Luna’s Fleet and the Discovery of the Discovery of the First Emanuel Point Shipwreck. The Florida

Anthropologist Vol. 62, Nos. 3-4.Smith, Roger, James Spirek, John Bratten, Della Scott-Ireton.

1995 The Emanuel Point Ship: Archaeological Investigation, 1992-1995. Florida Department of State, Division of Historical Resources, Bureau of Historical Research, Tallahassee.Smith, Roger C., John R. Bratten, J. Cozzi, and Keith Plaskett

1998 The Emanuel Point Ship: Archaeological Investigation, 1997-1998. Report of Investigations #68,

Archaeology Institute, University of West Florida, Pensacola.Walker, S.T.

1883 Mounds and Shell Heaps on the West Coast of Florida. Smithsonian Annual Report. - Download PDF Version