An Exploration for the Oldest European Colony on the American Gulf Coast (AD 1559)

by Caleb Curren

Contact Archeology Ink

Copyright 2012

Caleb Curren

Principal Investigator

Photo Samples of the research area at the mouth of Bayou Texar

The Beginning of the Expedition

The King of Spain was worried about the French stealing his gold and other precious metals and stones. The treasures were coming from Central America and South America by the shiploads and filling the coffers of the Spanish Crown. The French wanted some of the loot so they raided the fleets sailing back to Spain. The King responded. He ordered the Viceroy of Mexico to organize an expedition to sail to the northern Gulf Coast of the current United States and set up a colony to protect Spanish interests on land and sea. The Viceroy put his friend and veteran of the Coronado expedition to the Southwest in charge of the Gulf Coast colony. His name was Tristan de Luna. The fleet was outfitted with the very best supplies from the Mexican interior. They embarked from the coastal town of Vera Cruz and sailed into history.

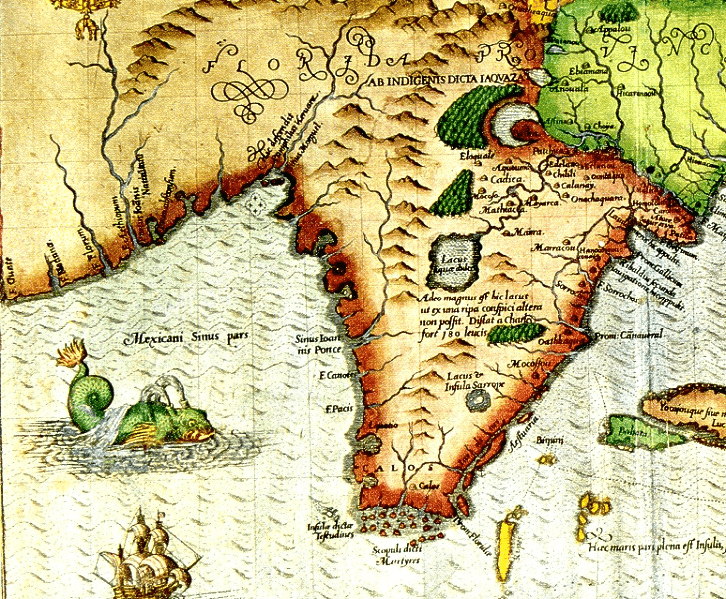

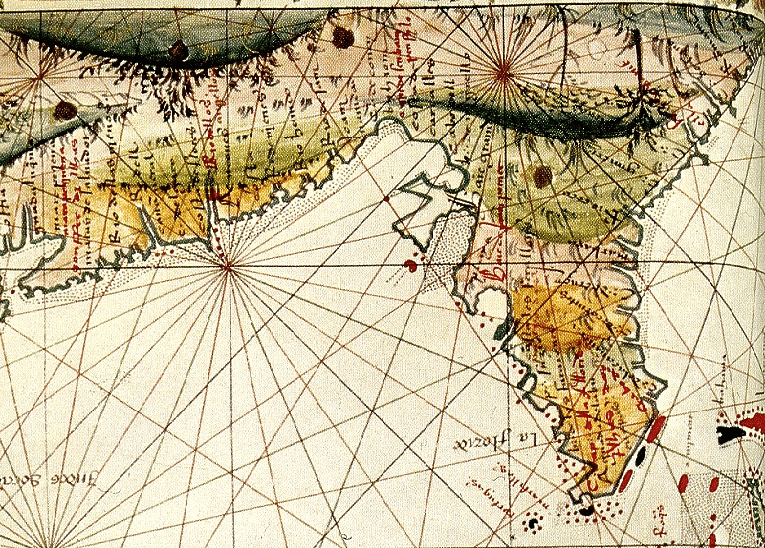

After a month of fair winds and foul, 1500 people from Mexico landed on a bay on the northern Gulf Coast of the present United States. The date was August 14, 1559. The expedition was, up to that time, the largest European colonization attempt ever made to the present-day United States. The Spanish colony was established 48 years before English Jamestown and 6 years before Spanish St. Augustine.

The name given to the colony is somewhat vague. Although the colony and bay were called several names, most common was Bahia de Santa Maria Filipina (Priestley 1928). The name was given in honor of the sainted Mary and the Spanish King Philip, thus, signifying the presence of church and state. A shortened name of the colony, Santa Maria, is used in this paper.

The colony personnel were given several assignments by the Spanish government, any one of which was a monumental undertaking. The colonists were charged with establishing three settlements: one on the Gulf Coast, one in the interior at fabled Aboriginal Coosa, and one on the Atlantic coast. All of the settlements were meant, primarily, to protect the Spanish treasure fleets passing along the Florida coast back to Spain. As if these assignments weren’t enough, the colonists were also ordered to secure precious metals for the king and the church and find an overland route back to Mexico. The mission was absolutely impossible for the time.

Crippled by a powerful hurricane days after landing at the Bay of Ochuse, the Spaniards struggled to keep a colony on the bay for over two years while attempting to establish outposts in the interior. In the end, the sick and starving Spanish retreated back to the Bay of Ochuse colony and eventually left on ships destined for Mexico and Cuba, relieved to be rid of their sufferings.

The discovery of the location of the Santa Maria colony would help us to better understand the culture of the 16th century European colonists and the native Aboriginal peoples. We are looking for that colony and have made some important discoveries.

The Specifics of the Colony Site

The Spanish were bold in their breakout of Europe into North and South America during the 1500s. They claimed the Americas and it worked for a time. They mined the gold and silver and shipped it back to Spain and the country grew into a world power. Then the Spanish got the attention of their competitors. France and Britain were the first to resist. Spanish ships were intercepted by “privateers,” licensed pirates, in the Atlantic and Caribbean on their way back to the homeland. Spain responded in kind. The Spanish king decreed that there would be colonies established in the southeast of North America to protect the precious metal shipments heading to Spain. The king contacted the viceroy of Mexico and instructed him to make it so.

A well supplied fleet of about a dozen ships was arranged by the viceroy and sent to the northern Gulf Coast from the Mexican port of Vera Cruz. The deep-water port of Pensacola Bay eventually became the landfall. They surmised that the bay was the same bay that the Soto expedition discovered and named it the Bay of Ochuse. They may or may not have been correct. None the less, the colony was established amid much hardship and lasted for over two years.

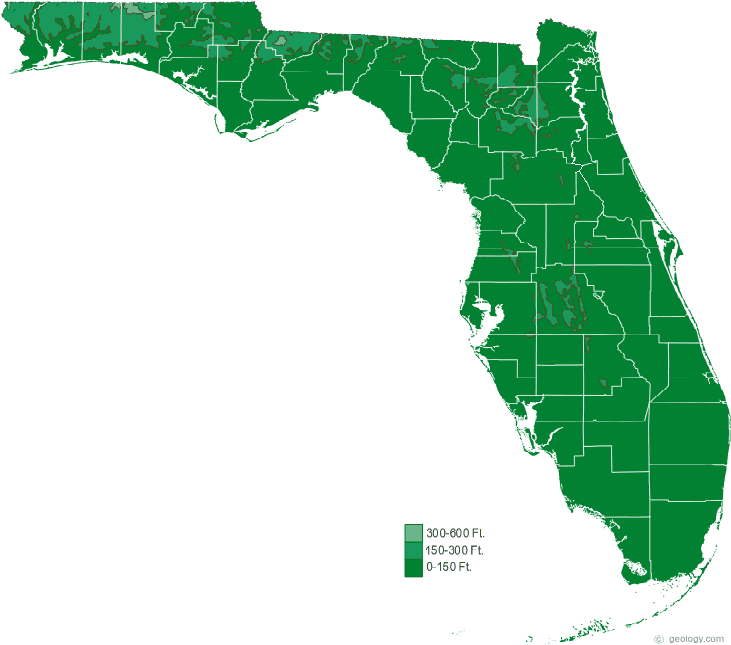

The Spanish left hundreds of pages of documentation relevant to their epic voyage. Among the papers was a description of where they chose to make their settlement. They said that it was inside a bay on a high area which overlooked the anchorage of their ships (La Rua Bluff?).

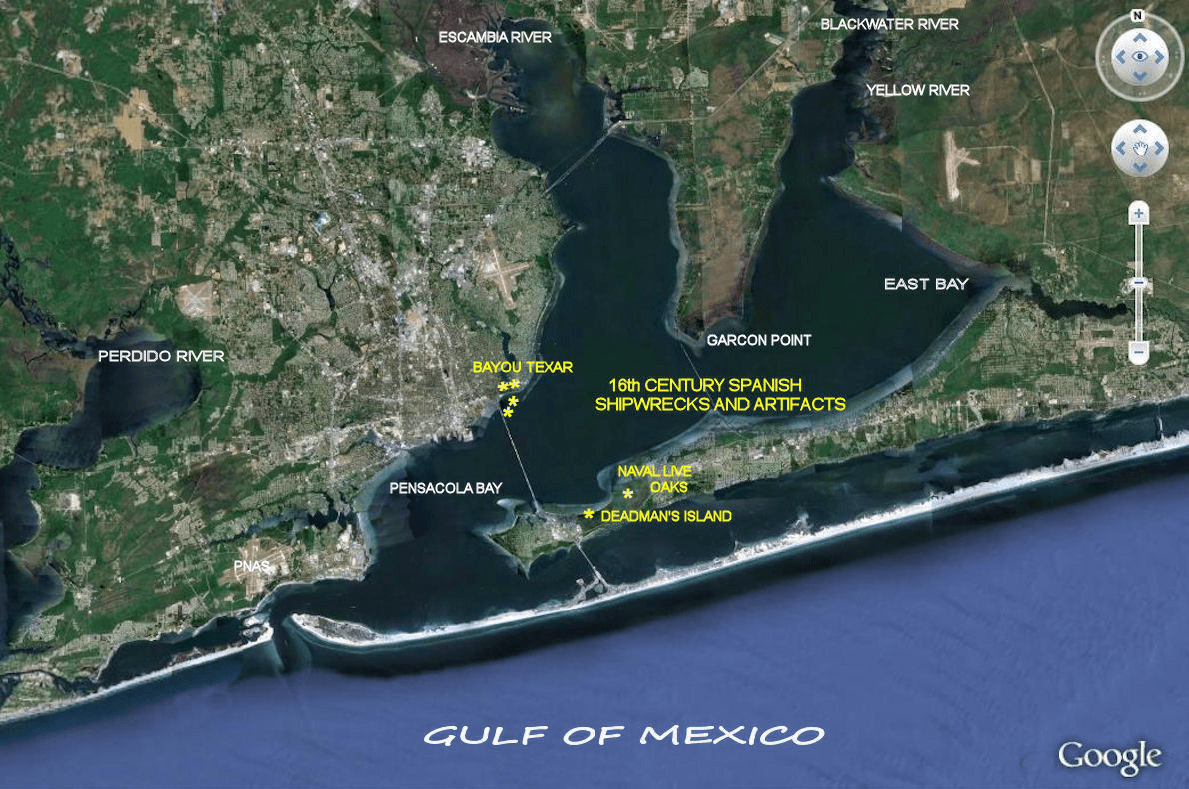

They recorded that a red bluff on a peninsula was visible to them across the bay and divided the bay east to west as a peninsula (Gulf Breeze Peninsula?). They also noted that after a hurricane crippled their fleet, they found supplies floating in a “creek” near their settlement (the narrow mouth of Bayou Texar?). A very logical location for that colony is near the mouth of Bayou Texar. Unusually high ground is there. 16th Century Spanish shipwrecks are relatively near the bay shore to the south. The shipwrecks were discovered and tested by the Florida Division of Historical Resources (Underwater Archaeology Program) and the University of West Florida.

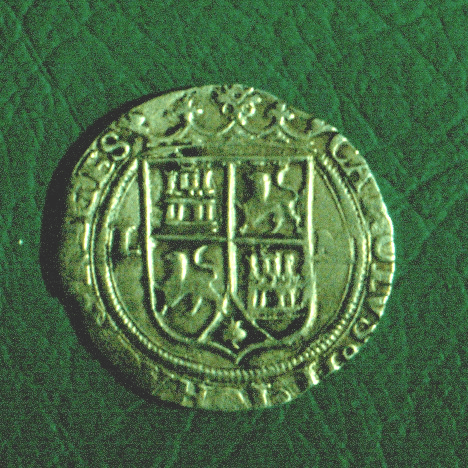

A silver coin and a copper coin from the 1500s have been found near the La Rua Bluff by local people. 16th century Spanish trade artifacts have been found in aboriginal sites across the bay. Negative evidence is also compelling. No 16th century Spanish artifacts have been found anywhere on Pensacola Bay except for the near proximity area of the mouth of Bayou Texar (shipwrecks, coins, pottery) and the Gulf Breeze peninsula (trade beads and pottery).

Recent Archeological Research Design

The archeological site of the Luna colony on Pensacola Bay has not been found. We are conducting an archeological survey to locate remains of that settlement. An enormous amount of archeological excavations have been conducted in the bay area of Pensacola. Interestingly, only four sites have produced artifacts from the mid-1500s. Four terrestrial site areas have produced Luna period artifacts. A silver coin known as a “Charles and Johanna” minted during the mid- 1500s was found along side a railroad track at the mouth of Bayou Texar by a young boy in the early 1900s. A local family in the 1950s-60s found 16th century Spanish trade items in native mounds on the Gulf Breeze peninsula across Pensacola Bay from the coin site. The State of Florida also found two mid-1500s shipwrecks just offshore of the coin site in the late 20th and early 21th centuries. The ships date to the time of the Luna colony. A second coin, copper minted in the late 1400s or early 1500s, has also been found near the mouth of Bayou Texar.

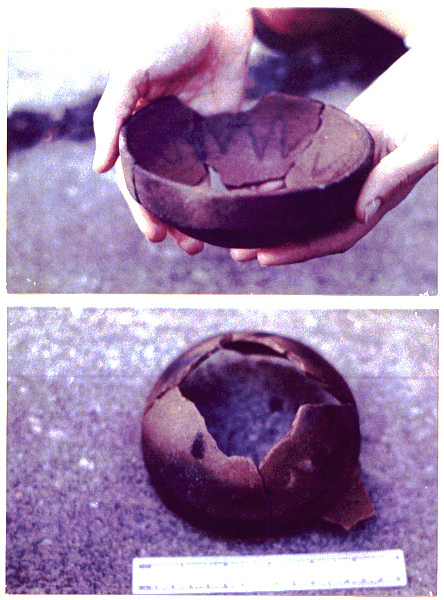

Spanish pottery of the same period has also be found near the mouth of Bayou Texar.

So where is the land based location of the colony of that bold attempt at colonization of 1559? It stands to reason that the colony would be near the shipwrecks and the Spanish artifact discoveries, but where? The following is a record of recent test excavations for the colony in the La Rua Bluff area (we coined the name for convenience). It should be remembered that this colony was the first attempt at European settlement on the northern Gulf Coast and hence a landmark of the cultural change of a continent.

Our research design is relatively simple and straight forward. We look for private property on high areas at the mouth of Bayou Texar which overlooks the anchorage of the two 16th century Spanish shipwrecks, as the Spanish noted. The geologic marine terrace is unique in this area in that it is very high ground overlooking Pensacola Bay, Bayou Texar, and the two shipwrecks found by the State of Florida. We ask permission to examine private lots. We interview the local homeowners for their knowledge of the area and any artifacts they might have recovered.

We perform subsurface tests with the aid of ground penetrating radar and metal detectors, excavate test units, make photographs, and keep records. This article presents some of these recent research endeavors. The following pages define each site and present the archeological evidence of Spanish occupations during the 1500s at the time of the first Spanish colony. We plan on continuing our research by raising funds for more research.

References and a Sample of Related Works

Bense, Judith A. and Debra Joy

1986 Archaeological Survey and Description of City-Owned Property. Report to the City of Pensacola from the University of West Florida.

Brame, James Y.

1960 The First Colony. Privately printed. Montgomery, Alabama.

Curren, Caleb

1994 The Search for Santa Maria, a 1559 Spanish Colony on the Northern Florida Coast. Pensacola Archeology Lab.

Curren, Caleb, Keith J. Little, and Harry O. Holstein

1989 Aboriginal Societies Encountered by the Tristan de Luna Expedition. The Florida Anthropologist 42 (4).

Cook, Gregory

2010 Emanuel Point Shipwrecks. Internet, Pensapedia.

Deagan, Kathleen

1987 Artifacts of the Spanish Colonies of Florida and the Caribbean 1500-1800. Smithsonian Institution.

Florida Anthropologist Sept.-Dec.

2009 Emanuel Point Shipwreck; a Collection of Papers. Vol. 62, nos. 3-4.

Head, Randolph

1980 Archeological Study of Florida Gulf Coast Indians. Student research paper. Univ. West Florida.

Holmes, Nicholas H. Sr.

1994 The Luna Expedition. The Soto States Anthropologist 93 (3-4).

Joy, Debra

1988 Initial Archaeological Summary of the City of Gulf Breeze, Florida. Reports of Investigations #15. Office of Cultural and Archaeological Research, University of West Florida, Pensacola.

Lazarus, Yulee, W.C. Lazarus, and Donald Sharon

1967 The Navy Liveoak Reservation and Cemetery Site, 8Sa36. Florida Anthropologist 20 (3-4).

Pensacola News Journal

1990 Coin Dates to the Days of de Luna. Wednesday, June 13, 1990. 1991 Pottery Holds Food for History. Saturday, June 29, 1991.

1993a On the Trail of Luna. Friday, July 16, 1993.

1993b Sunken Shipwreck Might be de Luna’s. Saturday, February 27, 1993. 1993c Wreck Could Be de Luna’s. Wednesday, March 3, 1993.

Priestley, Herbert Ingram

1928 The Luna Papers. Florida State Historical Society, Deland, Florida.

1936 Tristan de Luna, Conquistador of the Old South: A Study of Spanish Imperial Strategy. The Arthur H. Clark Company, Glendale, California.

Smith, Roger, James Spirek, John Bratten, and Della Scott-Ireton

1995 The Emanuel Point Ship Archaeological Investigations 1992-1995. Florida Dept. of State.

South, Stanley, Russell K. Skowronek, and Richard E. Johnson

1988 Spanish Artifacts from Santa Elena. Occasional Papers of the South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology. Anthropological Papers 7.

Tesar, Louis D.

1973 Archaeological Surveying and Testing of the Gulf Islands National Seashore, Part I. Hale G. Smith, editor. Department of Anthropology, Florida State University, Tallahassee.

Acknowledgements

A project such as this in a residential neighborhood cannot be accomplished without the cooperation of the homeowners. We have found that the property owners not only grant us permission to explore their property but are also personally interested in our findings.

We thank them all: the Browns, Carrs, Currans, Donovans, Heads, and Williams.

Thanks to Terry Berling for endorsing our research on La Rua Bluff and providing me with relaxing down time at Bimini. Thanks as well to the Tower East Group for providing office and lab space. Thanks to Chuck Pinson for the donation of funds and of many expensive hours of remote sensing as well as his cartographic skills. Thanks to Dr. Eugene Wilson for sharing his expertise on the geography of the area and his encouragement. Thanks to Jerry Gill for editing the manuscript and keeping us editorially correct. Thanks to Dick Barnes for keeping us plied with smoked mullet. Thanks to David Dodson for sharing his skills as a Spanish translator and historian, and for donating funds to the project. Thanks to Randolph Head for sharing his knowledge of the area and freely providing me with documents and artifacts. Thanks to Dr. Keith Little for donating his lab for preservation of significant iron artifacts we found. It should also be noted that our dogs Lucky and Tip kept the varmints in the woods away from the field team while we did our diligence.

We are not finished with this research. I suspect that before it’s over there will be many more folks to thank and data to report.

- Article

-

Photo Samples of the research area at the mouth of Bayou Texar

Research BoatArea of Spanish pottery and coinLa Rua Bluff from across Bayou TexarBallast stone areaThe Beginning of the Expedition

The King of Spain was worried about the French stealing his gold and other precious metals and stones. The treasures were coming from Central America and South America by the shiploads and filling the coffers of the Spanish Crown. The French wanted some of the loot so they raided the fleets sailing back to Spain. The King responded. He ordered the Viceroy of Mexico to organize an expedition to sail to the northern Gulf Coast of the current United States and set up a colony to protect Spanish interests on land and sea. The Viceroy put his friend and veteran of the Coronado expedition to the Southwest in charge of the Gulf Coast colony. His name was Tristan de Luna. The fleet was outfitted with the very best supplies from the Mexican interior. They embarked from the coastal town of Vera Cruz and sailed into history.

After a month of fair winds and foul, 1500 people from Mexico landed on a bay on the northern Gulf Coast of the present United States. The date was August 14, 1559. The expedition was, up to that time, the largest European colonization attempt ever made to the present-day United States. The Spanish colony was established 48 years before English Jamestown and 6 years before Spanish St. Augustine.

The name given to the colony is somewhat vague. Although the colony and bay were called several names, most common was Bahia de Santa Maria Filipina (Priestley 1928). The name was given in honor of the sainted Mary and the Spanish King Philip, thus, signifying the presence of church and state. A shortened name of the colony, Santa Maria, is used in this paper.

The colony personnel were given several assignments by the Spanish government, any one of which was a monumental undertaking. The colonists were charged with establishing three settlements: one on the Gulf Coast, one in the interior at fabled Aboriginal Coosa, and one on the Atlantic coast. All of the settlements were meant, primarily, to protect the Spanish treasure fleets passing along the Florida coast back to Spain. As if these assignments weren’t enough, the colonists were also ordered to secure precious metals for the king and the church and find an overland route back to Mexico. The mission was absolutely impossible for the time.

Crippled by a powerful hurricane days after landing at the Bay of Ochuse, the Spaniards struggled to keep a colony on the bay for over two years while attempting to establish outposts in the interior. In the end, the sick and starving Spanish retreated back to the Bay of Ochuse colony and eventually left on ships destined for Mexico and Cuba, relieved to be rid of their sufferings.

The discovery of the location of the Santa Maria colony would help us to better understand the culture of the 16th century European colonists and the native Aboriginal peoples. We are looking for that colony and have made some important discoveries.

The Specifics of the Colony Site

The Spanish were bold in their breakout of Europe into North and South America during the 1500s. They claimed the Americas and it worked for a time. They mined the gold and silver and shipped it back to Spain and the country grew into a world power. Then the Spanish got the attention of their competitors. France and Britain were the first to resist. Spanish ships were intercepted by “privateers,” licensed pirates, in the Atlantic and Caribbean on their way back to the homeland. Spain responded in kind. The Spanish king decreed that there would be colonies established in the southeast of North America to protect the precious metal shipments heading to Spain. The king contacted the viceroy of Mexico and instructed him to make it so.

A well supplied fleet of about a dozen ships was arranged by the viceroy and sent to the northern Gulf Coast from the Mexican port of Vera Cruz. The deep-water port of Pensacola Bay eventually became the landfall. They surmised that the bay was the same bay that the Soto expedition discovered and named it the Bay of Ochuse. They may or may not have been correct. None the less, the colony was established amid much hardship and lasted for over two years.

The Spanish left hundreds of pages of documentation relevant to their epic voyage. Among the papers was a description of where they chose to make their settlement. They said that it was inside a bay on a high area which overlooked the anchorage of their ships (La Rua Bluff?).

They recorded that a red bluff on a peninsula was visible to them across the bay and divided the bay east to west as a peninsula (Gulf Breeze Peninsula?). They also noted that after a hurricane crippled their fleet, they found supplies floating in a “creek” near their settlement (the narrow mouth of Bayou Texar?). A very logical location for that colony is near the mouth of Bayou Texar. Unusually high ground is there. 16th Century Spanish shipwrecks are relatively near the bay shore to the south. The shipwrecks were discovered and tested by the Florida Division of Historical Resources (Underwater Archaeology Program) and the University of West Florida.

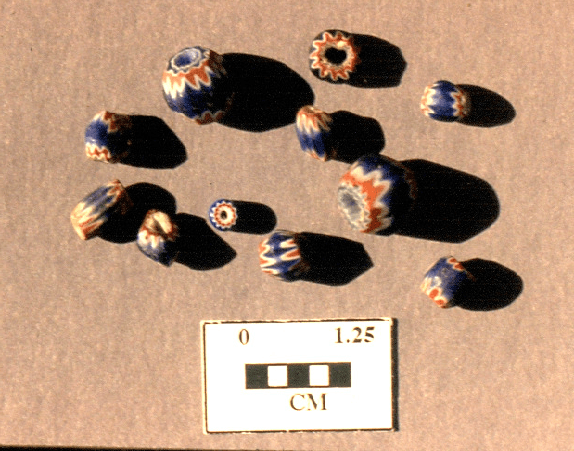

A silver coin and a copper coin from the 1500s have been found near the La Rua Bluff by local people. 16th century Spanish trade artifacts have been found in aboriginal sites across the bay. Negative evidence is also compelling. No 16th century Spanish artifacts have been found anywhere on Pensacola Bay except for the near proximity area of the mouth of Bayou Texar (shipwrecks, coins, pottery) and the Gulf Breeze peninsula (trade beads and pottery).

Recent Archeological Research Design

The archeological site of the Luna colony on Pensacola Bay has not been found. We are conducting an archeological survey to locate remains of that settlement. An enormous amount of archeological excavations have been conducted in the bay area of Pensacola. Interestingly, only four sites have produced artifacts from the mid-1500s. Four terrestrial site areas have produced Luna period artifacts. A silver coin known as a “Charles and Johanna” minted during the mid- 1500s was found along side a railroad track at the mouth of Bayou Texar by a young boy in the early 1900s. A local family in the 1950s-60s found 16th century Spanish trade items in native mounds on the Gulf Breeze peninsula across Pensacola Bay from the coin site. The State of Florida also found two mid-1500s shipwrecks just offshore of the coin site in the late 20th and early 21th centuries. The ships date to the time of the Luna colony. A second coin, copper minted in the late 1400s or early 1500s, has also been found near the mouth of Bayou Texar.

Spanish pottery of the same period has also be found near the mouth of Bayou Texar.

So where is the land based location of the colony of that bold attempt at colonization of 1559? It stands to reason that the colony would be near the shipwrecks and the Spanish artifact discoveries, but where? The following is a record of recent test excavations for the colony in the La Rua Bluff area (we coined the name for convenience). It should be remembered that this colony was the first attempt at European settlement on the northern Gulf Coast and hence a landmark of the cultural change of a continent.

Our research design is relatively simple and straight forward. We look for private property on high areas at the mouth of Bayou Texar which overlooks the anchorage of the two 16th century Spanish shipwrecks, as the Spanish noted. The geologic marine terrace is unique in this area in that it is very high ground overlooking Pensacola Bay, Bayou Texar, and the two shipwrecks found by the State of Florida. We ask permission to examine private lots. We interview the local homeowners for their knowledge of the area and any artifacts they might have recovered.

We perform subsurface tests with the aid of ground penetrating radar and metal detectors, excavate test units, make photographs, and keep records. This article presents some of these recent research endeavors. The following pages define each site and present the archeological evidence of Spanish occupations during the 1500s at the time of the first Spanish colony. We plan on continuing our research by raising funds for more research.

- References

-

References and a Sample of Related Works

Bense, Judith A. and Debra Joy

1986 Archaeological Survey and Description of City-Owned Property. Report to the City of Pensacola from the University of West Florida.

Brame, James Y.

1960 The First Colony. Privately printed. Montgomery, Alabama.

Curren, Caleb

1994 The Search for Santa Maria, a 1559 Spanish Colony on the Northern Florida Coast. Pensacola Archeology Lab.

Curren, Caleb, Keith J. Little, and Harry O. Holstein

1989 Aboriginal Societies Encountered by the Tristan de Luna Expedition. The Florida Anthropologist 42 (4).

Cook, Gregory

2010 Emanuel Point Shipwrecks. Internet, Pensapedia.

Deagan, Kathleen

1987 Artifacts of the Spanish Colonies of Florida and the Caribbean 1500-1800. Smithsonian Institution.

Florida Anthropologist Sept.-Dec.

2009 Emanuel Point Shipwreck; a Collection of Papers. Vol. 62, nos. 3-4.

Head, Randolph

1980 Archeological Study of Florida Gulf Coast Indians. Student research paper. Univ. West Florida.

Holmes, Nicholas H. Sr.

1994 The Luna Expedition. The Soto States Anthropologist 93 (3-4).

Joy, Debra

1988 Initial Archaeological Summary of the City of Gulf Breeze, Florida. Reports of Investigations #15. Office of Cultural and Archaeological Research, University of West Florida, Pensacola.

Lazarus, Yulee, W.C. Lazarus, and Donald Sharon

1967 The Navy Liveoak Reservation and Cemetery Site, 8Sa36. Florida Anthropologist 20 (3-4).

Pensacola News Journal

1990 Coin Dates to the Days of de Luna. Wednesday, June 13, 1990. 1991 Pottery Holds Food for History. Saturday, June 29, 1991.

1993a On the Trail of Luna. Friday, July 16, 1993.

1993b Sunken Shipwreck Might be de Luna’s. Saturday, February 27, 1993. 1993c Wreck Could Be de Luna’s. Wednesday, March 3, 1993.

Priestley, Herbert Ingram

1928 The Luna Papers. Florida State Historical Society, Deland, Florida.

1936 Tristan de Luna, Conquistador of the Old South: A Study of Spanish Imperial Strategy. The Arthur H. Clark Company, Glendale, California.

Smith, Roger, James Spirek, John Bratten, and Della Scott-Ireton

1995 The Emanuel Point Ship Archaeological Investigations 1992-1995. Florida Dept. of State.

South, Stanley, Russell K. Skowronek, and Richard E. Johnson

1988 Spanish Artifacts from Santa Elena. Occasional Papers of the South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology. Anthropological Papers 7.

Tesar, Louis D.

1973 Archaeological Surveying and Testing of the Gulf Islands National Seashore, Part I. Hale G. Smith, editor. Department of Anthropology, Florida State University, Tallahassee.

- Download PDF Version

- Acknowledgements

-

Acknowledgements

A project such as this in a residential neighborhood cannot be accomplished without the cooperation of the homeowners. We have found that the property owners not only grant us permission to explore their property but are also personally interested in our findings.

We thank them all: the Browns, Carrs, Currans, Donovans, Heads, and Williams.

Thanks to Terry Berling for endorsing our research on La Rua Bluff and providing me with relaxing down time at Bimini. Thanks as well to the Tower East Group for providing office and lab space. Thanks to Chuck Pinson for the donation of funds and of many expensive hours of remote sensing as well as his cartographic skills. Thanks to Dr. Eugene Wilson for sharing his expertise on the geography of the area and his encouragement. Thanks to Jerry Gill for editing the manuscript and keeping us editorially correct. Thanks to Dick Barnes for keeping us plied with smoked mullet. Thanks to David Dodson for sharing his skills as a Spanish translator and historian, and for donating funds to the project. Thanks to Randolph Head for sharing his knowledge of the area and freely providing me with documents and artifacts. Thanks to Dr. Keith Little for donating his lab for preservation of significant iron artifacts we found. It should also be noted that our dogs Lucky and Tip kept the varmints in the woods away from the field team while we did our diligence.We are not finished with this research. I suspect that before it’s over there will be many more folks to thank and data to report.

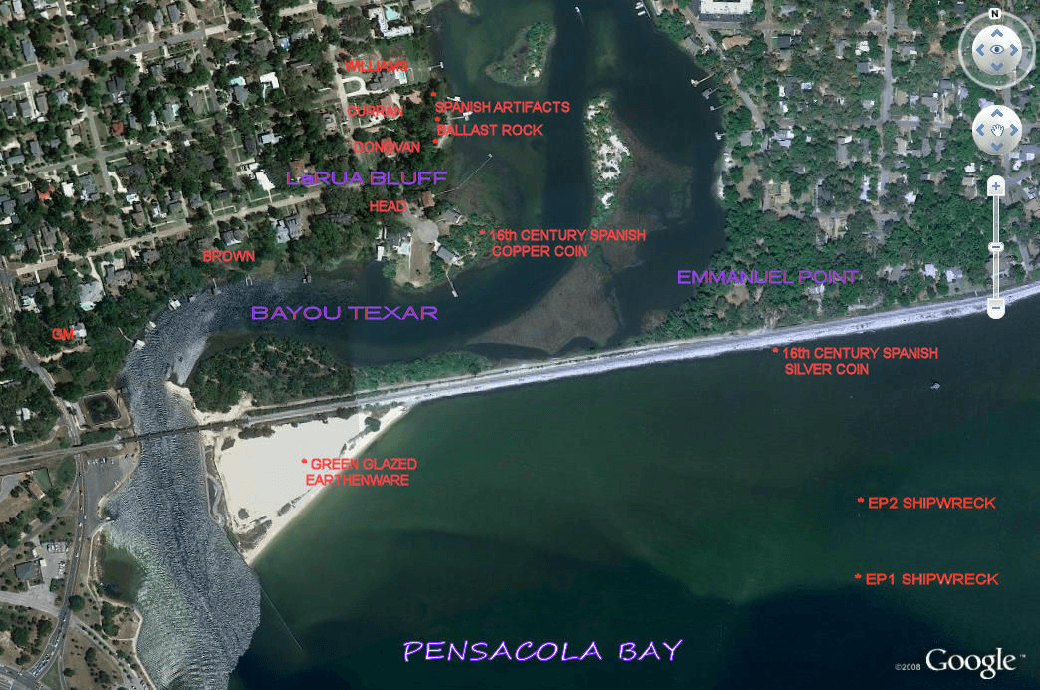

Figure 3: Maps of 16th Century Spanish Artifacts in Pensacola Bay

(locations are not exact so as to protect the sites)

Although considerable archeological research has been conducted on the bay, known 16th Century Spanish artifacts have been found only in these locations. It may be an indication of the activities of the Luna Colony.

The Donovan Site

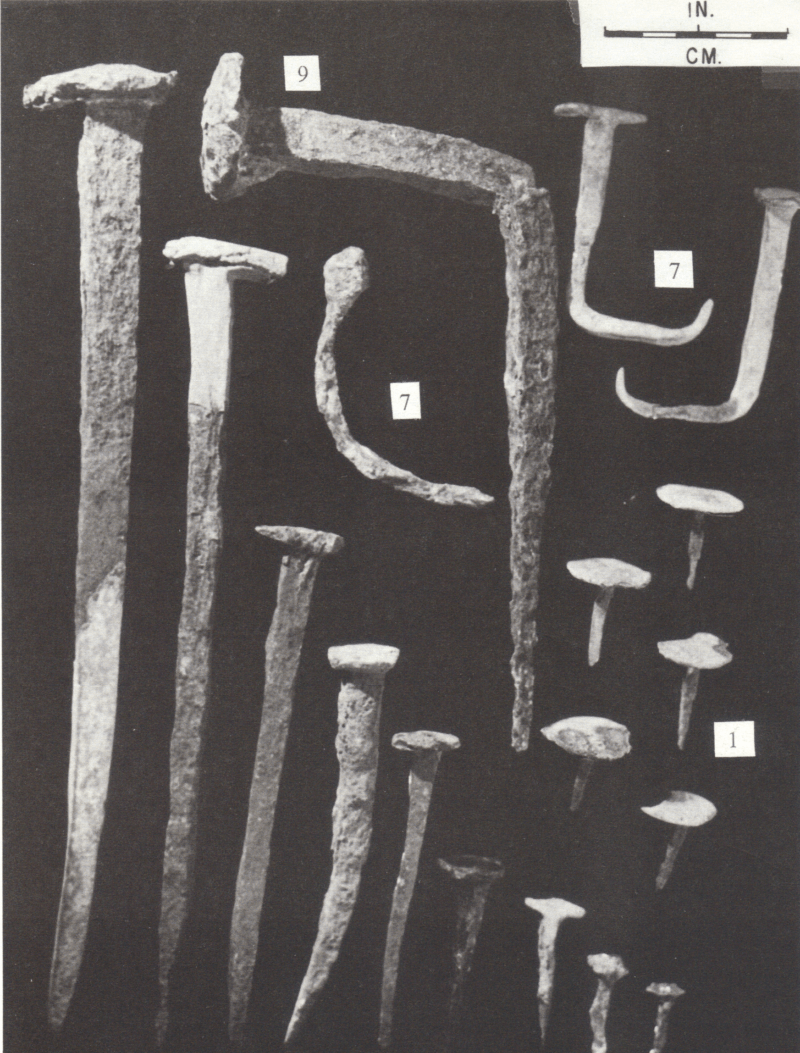

We obtained permission to dig test excavations on this property. Eight shovel tests and one test unit (1×1 meter in size) were dug on the property. Ground penetrating radar and metal detectors were also used. Numerous 20th century artifacts were recovered and two colonial period artifacts were found. A ceramic sherd (salt glazed stoneware) and an iron spike were found in one of the shovel tests. Stoneware was made from the 1300s to the 1700s and the iron spike appeared to be from ship manufacture similar to the type found at the Spanish colony site of Santa Elena on the Carolina coast dating to the mid to late 1500s (South et al. 1988).

Interestingly, historic ballast stones, many buried, are also found abundantly on this property. That is not the case for many other lots we have examined. All of this archeological data were clues to be sure but they are not completely definitive of the Luna Colony location but suggestive none the less.

Figure 4: Metal Detecting, view to northeast

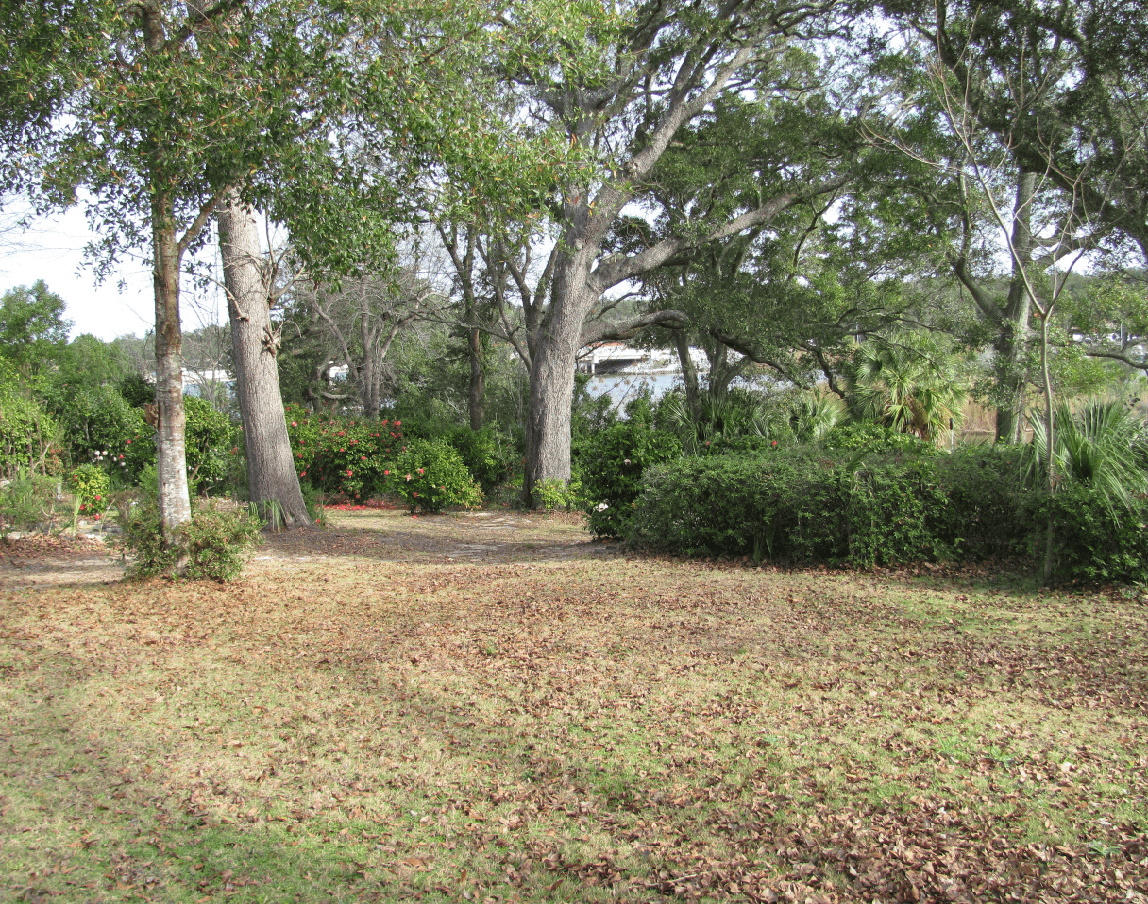

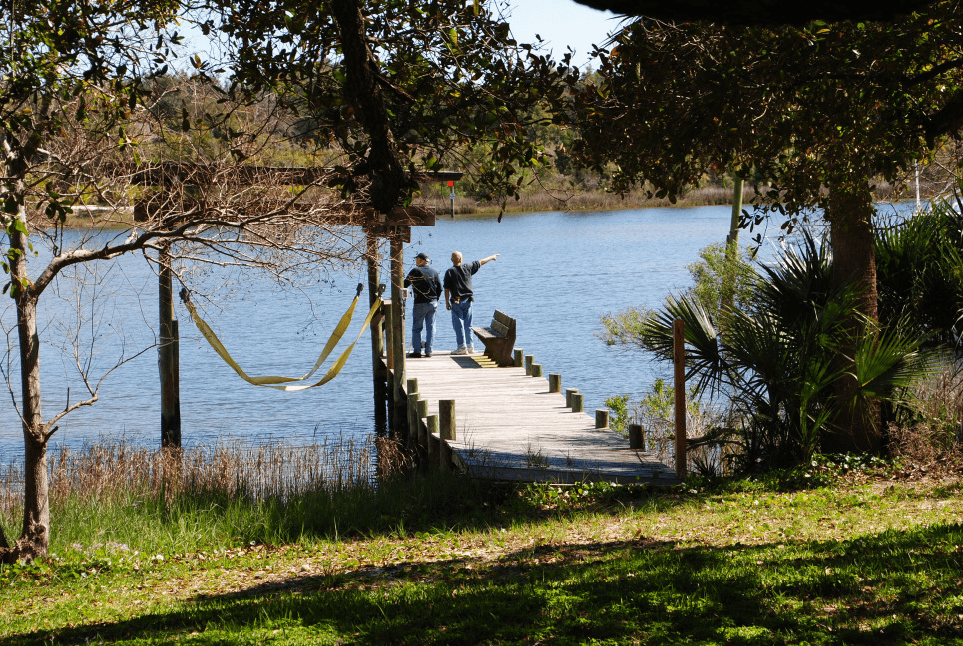

Figure 5: View to Northeast across Bayou Texar, area of ship spike and ballast stones

Figure 6: Donovan Property: View of property where Spanish pottery and iron spike was discovered

Figure 7: View of Donovan home and elevated marine terrace above Bayou Texar and Pensacola Bay

Figure 8: Donovan Property, screening and metal detecting

Figure 9: Donovan Property, Unit #1, 1×1 meter. Artifacts were found in the upper 20 cm dark brown sandy loam zone.

Tan sand at base is culturally sterile

Figure 10: Iron Ship Spike

Figure 11: Salt Glazed Stoneware

Figure 12: Nails from the Santa Elena Spanish colony site on the Atlantic coast (1566-1587). Note the large nails and spikes on the left side of the photo (likely ship spikes) (South et al. 1988)

Figure 13: View of Donovan property from Bayou Texar and excavating 1×1 meter test unit on the property

The Brown Site

Figure 14: Photos of the dramatic bluff at the mouth of Bayou Texar. European colonial earthenware in small quantities has been found eroding from this marine terrace. Two Spanish shipwrecks have been found in Pensacola Bay within clear site of this bluff. Two Spanish coins from the 1500s have also been found in the area.

The Currin Site

Fig. 15: (top) Historical colonial ceramics from the property, most from the 1700s. The artifacts were found by the Currin family in their garden and their dog yard.

(middle) View of Bayou Texar at the Currin Site.

(bottom) Aboriginal ceramic sherds dating from the oldest cultural period of pottery manufacture in North America (fiber tempered Gulf Formational Period , circa 3,000- 4,000 years before present). These artifacts indicate a long-term use of La Rua Bluff as a habitation area. Could the Luna Colony have used the area as well?

The Bonifay Coin (8Es1)

The coin and the area are figured in the next few pages. Sixty something years later marine archeologists found two shipwrecks of the period just offshore from the same bayshore.

refs: (Curren 1994; Pensacola News Journal, 1990)

Bottom: tip of the peninsula where the coin was found.

The Head Dredge Site

Green Glazed Spanish Pottery

The Naval Live Oaks Cemetery (8SR36)

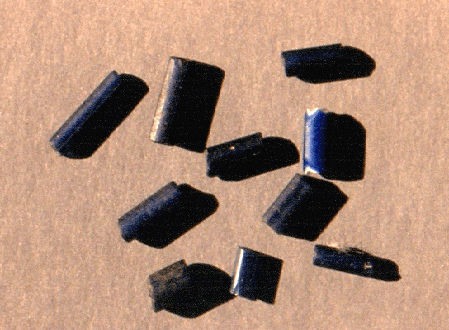

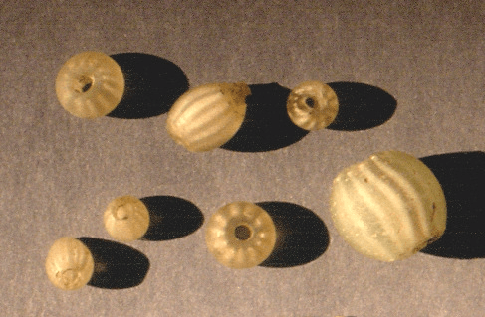

The Head Site is one of the most important Spanish contact sites on the northern Gulf Coast. It is currently protected under the Federal Parks system. The Naval Live Oaks Park is located on the southern reaches of Pensacola Bay and includes the Head Site. The site was dug by a local family in the 1960s. It is directly across Pensacola Bay from the mouth of Bayou Texar where we are testing.

The following pages include a sample of glass trade beads from the site: faceted chevrons, nueva cadiz, gooseberries, and others. It is but a sample of the artifacts found at this important burial mound complex and village.

An analysis of a sample of the glass trade beads from the site conducted by the Pensacola Historical Society in the early 1990s concluded: faceted chevrons = 11, Gooseberry = 7, turquoise = 22, nueva cadiz = 9. Currently, an analysis of the entire collection is being conducting by the University of West Florida.

refs. (Head 1980; Curren 1999, personal communication Randolph Head 2012)

Bottom: View of a portion of Naval Live Oaks Reservation where 16th Century artifacts were found

The Dead Mans' Island Site

Yellow fever hit the northern Gulf Coast hard during the 19th century. There is a small island just off a peninsula jutting into Pensacola Bay.

It took it’s name from the scourge of disease that killed many. It also contains some important artifacts from the time of the first Europeans who came into the bay. The objects may be from the Tristan de Luna expedition or even the Hernando de Soto expedition (AD 1539-1560).

refs: (Curren, Caleb, 1994; personal communication, Wayne Farrior, 1997)

Conclusions and Continuing Research Design

Have we proven conclusively the location of the important first European colony on the northern Gulf Coast ? No.

Do we have evidence of the possibility of the colony location ? Yes. It may be on La Rua Bluff in the yards of the current residents. The Spanish pottery and coins and shipwrecks were found near the mouth of Bayou Texar cannot be ignored.

Why is this colony research identification so important ? The 16th century was one of the most amazing periods in the history of humankind. Huge changes were initiated, some for the better, some for the worse. A whole new continent had been discovered. It was full of riches. It was also full of humans who did not look or act like the people on those exploration ships which sailed from Europe. The interchange between the two continents of Europe and North America is astounding.

The discovery of the Luna Colony is a small part of that story but still an important part. Spain had decided to establish a colony in this relatively unknown land. To be able to identify that location would help to locate inland European settlements as well as Native Chiefdoms noted by the Spanish chroniclers of the 1500s. The early history of this country could be better understood with these discoveries.

Our plan is to study the historic maps, continue to work with the landowners, excavate test units, record the results, use remote sensing technology, and publish articles. The results will be research designs for continued research.

Mouth of Bayou Texar. The creek where the Luna colony people found their supplies floating after the Hurricane ?