A Queen’s Pearl from the Lower Alabama River?

by Caleb Curren

October 2018

(an update from a 2016 Archeology Ink. Journal article: Archeologyink.com)

A treasure trove was discovered in the current southeastern United States by a Spanish expedition led by Hernando de Soto in May of 1540. The treasure was likely located in present-day South Carolina. The Spaniards found it in a powerful Native chiefdom named Cofachiqui (Ko-fa-chek-kee).

The chiefdom was led by a dynamic Queen. Spanish strangers had arrived in her domain with all their military prowess and the Queen wanted to get rid of them. This queen was unique in that she was a woman. We do not know how she rose to her prominence nor do we even know her name other than the Queen of Cofachiqui. She was obviously a very powerful leader.

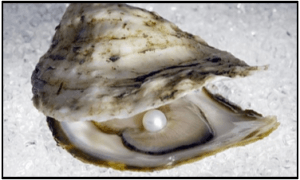

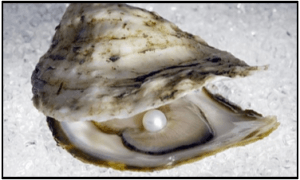

(Contemporary freshwater pearl laying in a mussel shell. Photo credit, Livia Bueno.)

She showed the Spaniards two temple buildings atop earthen mounds located in her domain. Incredible treasures were housed in the temples along with burials of her ancestors. The Spaniards looked on in awe upon the vast array of copper and shell objects along with elegant clothing and weapons of immense beauty and fine workmanship.

The Spaniards left most of the objects untouched. There was just too much booty to take with them. They planned to report the treasure to the King of Spain and return to the area at a later time. That never happened. Most of the Spaniards died years later from being killed by Natives before getting to friendly territory in Spanish-controlled Mexico. The Spaniards did manage to take with them several split cane chests filled with freshwater pearls. Mules carried the chests through the present-day states of South Carolina,Tennessee, and Alabama before a catastrophe struck.

The chests of pearls were lost at the great Battle of Mabila in southwest Alabama when the Natives ambushed the Soto army. At least one of those beads may have survived the battle (Curren 1987:41). A drilled freshwater pearl was found in a burial of high status persons on the lower Alabama River in a plowed down burial mound measuring 50 feet in diameter and 2 feet high in 1899. The discoverer, Clarence B. Moore of the Philadelphia Academy of Sciences, reported on the mound burials, one of which contained the drilled pearl:

One of the bunches (multiple burials in one grave) had six femurs of adults with two skulls and other bones of adults, and at one side the skull and certain bones of an infant … (with the burials were found) two undecorated, circular gorgets of shell, both badly broken; six massive shell beads, finely preserved; numerous glass beads; one small sheet copper bead; one perforated pearl … the only one met with by us in Alabama … (Moore 1899: 291-296).

Did that drilled pearl come from the Queen’s treasury? If so, does it provide a clue to the general location of the Battle of Mabila?

Perhaps we should start at the original description of the treasure site. The historic setting of the original discovery of the Queen’s pearls in Cofachiqui is best described by the chroniclers of the Soto expedition themselves.

… there were great quantities of pearls… All now rejoiced to find so much wealth in one place… The ceiling of the temple, from the walls upward, was adorned like the roof outside with designs of shells interspersed with strand of pearls … even though all might load both themselves and their horses (there being more than nine hundred men and upwards of three hundred beasts), they would never be able to remove from the temple all the pearls it contained. (Garcilaso de la Vega, son of a Spanish Conquistador and an Inca Noblewoman: Varner and Varner 1980:313).

… (Soto) opened a mosque (temple), in which were interred the bodies of the chief personages of that country. We took from it a quantity of pearls … ( Luys Hernandez de Biedma, representative of the King of Spain for the expedition: Bourne 1904-Vol. II:14).

They took from there some two hundred pounds of pearls and when the woman chief saw that the Christians set much store by them, she said: “Do you hold that of much account? Go to Talimeco, my village, and you will find so many that your horses cannot carry them.” (Rodrigo Ranjel, personal secretary of Hernando de Soto: Bourne 1904-Vol. II:100-102).

The Cacica (the Queen), observing that the Christians valued pearls, told the Governor (Soto) if he should order some sepulchers (temples) that were in the town to be searched, he would find many (pearls); and if he chose to send to those (temples) that were in the uninhabited towns, he might load all his horses with them. They examined those in the town, and found three hundred and fifty pounds weight of pearls, and figures of babies and birds made of them. (The Gentleman of Elvas, an unknown Portuguese Knight: Bourne 1904-Vol. I:66).

There is no doubt that the Soto army came across a Queen of a very rich Native Chiefdom in the current southeastern United States. Many freshwater pearls were found in burials of the ancestors of her kingdom. That fact is substantiated by the secretary of Soto, the representative of the King of Spain, a knight of Portugal, and a scribe who wrote of two participants on the expedition.

The Spaniards took chests of pearls from the temples of that region. The ploy of the Queen worked. She gave the Soto army the treasures they wanted and got them to leave her realm without major conflict with her people. The Spanish took her hostage for safe passage through her territory as was their custom. She mysteriously escaped along the trail in the late night.

(A Native Queen from the Southeast being carried on a litter by her subjects.

(A Native Queen from the Southeast being carried on a litter by her subjects.

A public domain image from the 16th-Century collections of DeBry and White.)

The loss of the pearls of the Queen was documented by the Spaniards at the battle of Mabila some seven months after taking them. The following quotes record those loses.

The clothing the Christians carried with them, the ornaments for saying mass, and the pearls, were all burned there (Mabila) … (The Gentleman of Elvas: Bourne 1904-Vol. I:97).

And the fire (during the Mabila battle) in its course burned the two hundred odd pounds of pearls that they had … (Ranjel, secretary of Soto: Bourne 1904-Vol. II:127).

Concerning the drilled freshwater pearl found on the lower Alabama River. Did the pearl bead found in 1899 on the lower Alabama River survive the Battle of Mabila and end up as a special item in a local Native burial? Professor Moore noted the rarity of the pearl bead in the publication of his explorations of the Alabama River: (With the Native burial was) one perforated pearl, the only one met with by us in Alabama (Moore 1899:295).

(by artist Herb Roe in an article from the Alabama News Center.

Author, Justin Fox, Nov. 8, 2016.)

The Native burial with the pearl was found on the east side of the Alabama River. Most researchers have concluded that the battle site of Mabila is located somewhere on the west side of the Alabama River, some hypothesize in Clarke County. Native peoples came from many places in the region to fight the Spaniards at Mabila. “War Trophies” were reportedly taken back home from the battle by Natives. Was the freshwater pearl in the high status burial one of those trophies?

Contact Archeology Inc. conducted an extensive search for the freshwater pearl found by Professor Moore in 1889 on the lower Alabama River. The pearl was finally found in the research collections of the Smithsonian Institution in 2017.

(Freshwater drilled necklace pearl found by C. B. Moore 1899 from an archeological site in southern Monroe County, Alabama. Contact Archeology Inc. managed to get a photograph of the bead from the collections of the Smithsonian Institution,

Washington, D.C. in 2017.)

Much research remains, both in the field and in the lab to solve the mystery of the freshwater pearl on the lower Alabama River and the location of the Battle of Mabila in Clarke County, Alabama.

The Queen of Cofachiqui was a shrewd ruler. She managed to get the Spaniards out of her territory and save her people from destruction and escape her own captivity. A single pearl from her treasury, ironically, might be a major clue to the eventual discovery of the Battle of Mabila, a linchpin along the route of the Soto Army through the Southeast and a key to the lives of the indigenous peoples of the region.

References

Bourne, Edward Gaylord

1904a Narratives of the Career of Hernando de Soto Vol. 1. A.S. Barnes and Company. New York.

1904b Narratives of the Career of Hernando de Soto Vol. 2. A.S. Barnes and Company. New York.

Curren, Caleb

1987 The Route of the Soto Army Through Alabama. Alabama De Soto Commission Working Paper #3.

Moore, Clarence B.

1899 Certain Aboriginal Remains of the Alabama River. Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia.

Varner, John and Jeanette

1951 The Florida of the Inca. The University of Texas Press.

- Article

-

A treasure trove was discovered in the current southeastern United States by a Spanish expedition led by Hernando de Soto in May of 1540. The treasure was likely located in present-day South Carolina. The Spaniards found it in a powerful Native chiefdom named Cofachiqui (Ko-fa-chek-kee).

The chiefdom was led by a dynamic Queen. Spanish strangers had arrived in her domain with all their military prowess and the Queen wanted to get rid of them. This queen was unique in that she was a woman. We do not know how she rose to her prominence nor do we even know her name other than the Queen of Cofachiqui. She was obviously a very powerful leader.

(Contemporary freshwater pearl laying in a mussel shell. Photo credit, Livia Bueno.)

She showed the Spaniards two temple buildings atop earthen mounds located in her domain. Incredible treasures were housed in the temples along with burials of her ancestors. The Spaniards looked on in awe upon the vast array of copper and shell objects along with elegant clothing and weapons of immense beauty and fine workmanship.

The Spaniards left most of the objects untouched. There was just too much booty to take with them. They planned to report the treasure to the King of Spain and return to the area at a later time. That never happened. Most of the Spaniards died years later from being killed by Natives before getting to friendly territory in Spanish-controlled Mexico. The Spaniards did manage to take with them several split cane chests filled with freshwater pearls. Mules carried the chests through the present-day states of South Carolina,Tennessee, and Alabama before a catastrophe struck.

The chests of pearls were lost at the great Battle of Mabila in southwest Alabama when the Natives ambushed the Soto army. At least one of those beads may have survived the battle (Curren 1987:41). A drilled freshwater pearl was found in a burial of high status persons on the lower Alabama River in a plowed down burial mound measuring 50 feet in diameter and 2 feet high in 1899. The discoverer, Clarence B. Moore of the Philadelphia Academy of Sciences, reported on the mound burials, one of which contained the drilled pearl:

One of the bunches (multiple burials in one grave) had six femurs of adults with two skulls and other bones of adults, and at one side the skull and certain bones of an infant … (with the burials were found) two undecorated, circular gorgets of shell, both badly broken; six massive shell beads, finely preserved; numerous glass beads; one small sheet copper bead; one perforated pearl … the only one met with by us in Alabama … (Moore 1899: 291-296).

Did that drilled pearl come from the Queen’s treasury? If so, does it provide a clue to the general location of the Battle of Mabila?

Perhaps we should start at the original description of the treasure site. The historic setting of the original discovery of the Queen’s pearls in Cofachiqui is best described by the chroniclers of the Soto expedition themselves.

… there were great quantities of pearls… All now rejoiced to find so much wealth in one place… The ceiling of the temple, from the walls upward, was adorned like the roof outside with designs of shells interspersed with strand of pearls … even though all might load both themselves and their horses (there being more than nine hundred men and upwards of three hundred beasts), they would never be able to remove from the temple all the pearls it contained. (Garcilaso de la Vega, son of a Spanish Conquistador and an Inca Noblewoman: Varner and Varner 1980:313).

… (Soto) opened a mosque (temple), in which were interred the bodies of the chief personages of that country. We took from it a quantity of pearls … ( Luys Hernandez de Biedma, representative of the King of Spain for the expedition: Bourne 1904-Vol. II:14).

They took from there some two hundred pounds of pearls and when the woman chief saw that the Christians set much store by them, she said: “Do you hold that of much account? Go to Talimeco, my village, and you will find so many that your horses cannot carry them.” (Rodrigo Ranjel, personal secretary of Hernando de Soto: Bourne 1904-Vol. II:100-102).

The Cacica (the Queen), observing that the Christians valued pearls, told the Governor (Soto) if he should order some sepulchers (temples) that were in the town to be searched, he would find many (pearls); and if he chose to send to those (temples) that were in the uninhabited towns, he might load all his horses with them. They examined those in the town, and found three hundred and fifty pounds weight of pearls, and figures of babies and birds made of them. (The Gentleman of Elvas, an unknown Portuguese Knight: Bourne 1904-Vol. I:66).

There is no doubt that the Soto army came across a Queen of a very rich Native Chiefdom in the current southeastern United States. Many freshwater pearls were found in burials of the ancestors of her kingdom. That fact is substantiated by the secretary of Soto, the representative of the King of Spain, a knight of Portugal, and a scribe who wrote of two participants on the expedition.

The Spaniards took chests of pearls from the temples of that region. The ploy of the Queen worked. She gave the Soto army the treasures they wanted and got them to leave her realm without major conflict with her people. The Spanish took her hostage for safe passage through her territory as was their custom. She mysteriously escaped along the trail in the late night.

(A Native Queen from the Southeast being carried on a litter by her subjects.

(A Native Queen from the Southeast being carried on a litter by her subjects.

A public domain image from the 16th-Century collections of DeBry and White.)The loss of the pearls of the Queen was documented by the Spaniards at the battle of Mabila some seven months after taking them. The following quotes record those loses.

The clothing the Christians carried with them, the ornaments for saying mass, and the pearls, were all burned there (Mabila) … (The Gentleman of Elvas: Bourne 1904-Vol. I:97).

And the fire (during the Mabila battle) in its course burned the two hundred odd pounds of pearls that they had … (Ranjel, secretary of Soto: Bourne 1904-Vol. II:127).

Concerning the drilled freshwater pearl found on the lower Alabama River. Did the pearl bead found in 1899 on the lower Alabama River survive the Battle of Mabila and end up as a special item in a local Native burial? Professor Moore noted the rarity of the pearl bead in the publication of his explorations of the Alabama River: (With the Native burial was) one perforated pearl, the only one met with by us in Alabama (Moore 1899:295).

(by artist Herb Roe in an article from the Alabama News Center.

Author, Justin Fox, Nov. 8, 2016.)The Native burial with the pearl was found on the east side of the Alabama River. Most researchers have concluded that the battle site of Mabila is located somewhere on the west side of the Alabama River, some hypothesize in Clarke County. Native peoples came from many places in the region to fight the Spaniards at Mabila. “War Trophies” were reportedly taken back home from the battle by Natives. Was the freshwater pearl in the high status burial one of those trophies?

Contact Archeology Inc. conducted an extensive search for the freshwater pearl found by Professor Moore in 1889 on the lower Alabama River. The pearl was finally found in the research collections of the Smithsonian Institution in 2017.

(Freshwater drilled necklace pearl found by C. B. Moore 1899 from an archeological site in southern Monroe County, Alabama. Contact Archeology Inc. managed to get a photograph of the bead from the collections of the Smithsonian Institution,

Washington, D.C. in 2017.)Much research remains, both in the field and in the lab to solve the mystery of the freshwater pearl on the lower Alabama River and the location of the Battle of Mabila in Clarke County, Alabama.

The Queen of Cofachiqui was a shrewd ruler. She managed to get the Spaniards out of her territory and save her people from destruction and escape her own captivity. A single pearl from her treasury, ironically, might be a major clue to the eventual discovery of the Battle of Mabila, a linchpin along the route of the Soto Army through the Southeast and a key to the lives of the indigenous peoples of the region.

- References and Related Works

-

References

Bourne, Edward Gaylord

1904a Narratives of the Career of Hernando de Soto Vol. 1. A.S. Barnes and Company. New York.

1904b Narratives of the Career of Hernando de Soto Vol. 2. A.S. Barnes and Company. New York.

Curren, Caleb

1987 The Route of the Soto Army Through Alabama. Alabama De Soto Commission Working Paper #3.

Moore, Clarence B.

1899 Certain Aboriginal Remains of the Alabama River. Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia.

Varner, John and Jeanette

1951 The Florida of the Inca. The University of Texas Press.

- Download PDF Version