Mapping the De Soto Route Through South Alabama;

In the Chroniclers Own Words

by: Caleb Curren

Contact Archeology Inc (CAI)

Published by Archeology Ink, an Online Research Journal February, 2025

(Archeologyink.com)

February 2025

Edits by Pamela Corey and David Dodson

In this Article:

- Introduction

- The Major Chroniclers Who Recorded the Events of the Soto Expedition

- The Bay of Ochuse and the Anchorage of the Soto Supply Fleet

- The Journey to Mabila

- The Arrival at Mabila, the Battle, and Afterwards

- The Necessary Archeological Criteria to Identify the Site of Mabila

- Historic Documents of the 1700s Provide Possible Evidence of the Location of Mabila Leaving the Town of Mabila

- The Journey into the Territory of Pafallaya

- Current Archeological Investigations in the Lower Warrior River Basin

- The Territory of the Chicasa

- The “Official” Mabila Location

- General Summary

- A Sample of Related Archeological and Historical Sources

Introduction

One of the most long-lived archeological mysteries in all of the Americas has yet to be resolved. Researchers have been trying to solve the mystery of the location of the battle site of Mabila for well over a hundred years. The Native town of Mabila was the site of a major 1540 battle fought between the Spanish army led by Hernando de Soto and Native Mississippian Period warriors. The site is a key to defining the geographic extent of the Mabila Chiefdom based on Native artifacts in association with Spanish artifacts in the context of the known date of the battle, October 18, 1540.

After the battle, the Spanish stayed in the Mabila area for about a month recovering from their wounds and burying their dead. Hundreds or perhaps thousands of people died at the battle site. The concentration of Spanish artifacts from the battle and their month long stay in the Mabila should aid in identifying the site. The discovery of the site would define the territory of the Native Chiefdom of Mabila and would help define the locations of other Chiefdoms along the route inland throughout the Southeast. Historically, a number of researchers have proposed various locations for the site. Most agree that the site is in Alabama but the specific location of Mabila town has not been found.

The historical, archeological, and geographic information used in this article could help in locating this important site. The documents provided by the participants in the Soto Expedition are the first wide ranging geographic record of Native Chiefdoms in the current southern United States and as such are true anthropological treasures relating to these chiefdom level societies. (note: The spellings of the names of the Native towns and Chiefdoms vary among the Soto chroniclers. The reason is that the Natives did not have a written language. The Spanish were using one or more translators to convey the sound of the names, hence, the different spellings.)

Ironically, the Soto Expedition, while severely impacting the Chiefdoms of the region, left us with remarkably detailed records of the Native cultures. This article uses some of the quotes from the Spanish documents. Introductions of the Spanish chroniclers themselves are presented on the following page.

Depiction of the Battle of Mabila by artist Herb Roe.

The Major Chroniclers Who Recorded the Events of the Soto Expedition

The chroniclers of the Soto Expedition left us a treasure of detailed descriptions of the Native cultures, vegetation, wildlife, and terrain of the interior and coastal regions of the present day southeastern United States, as well as their own personal experiences. Those chroniclers are here listed alphabetically with brief details of their lives.

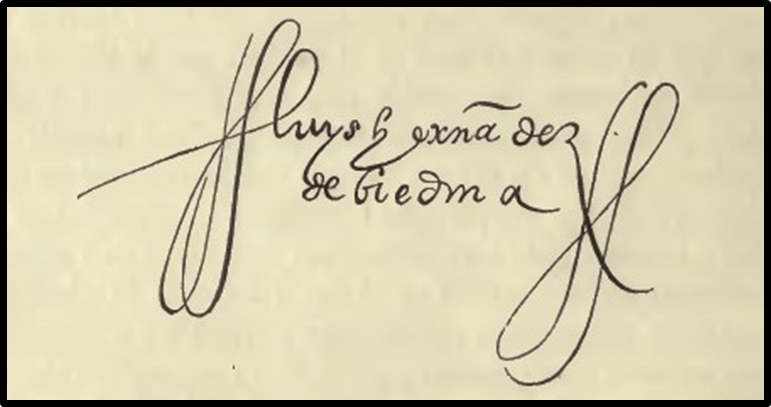

Hernandez de Biedma wrote his first-hand account in 1544 but it was not published until the mid-19th century (Bourne 1904b:xii). This was the official report of the expedition that Biedma, as factor of the king, (financial overseer), wrote to the King of Spain. It is the shortest and most general of all known accounts. It is most likely very reliable in its general nature. After all, Biedma was the king’s representative with his reputation at stake (Bourne 1904, Vol. 2).

We do not know the name of the writer of another of the Soto Expedition chroniclers. We do know that he hailed from the Portuguese town of Elvas, hence he is simply known as the “Gentleman of Elvas,” who was a member of the Soto Expedition. Whatever his name, he definitely wrote an important chronicle of the expedition which was published in 1557 but was more likely written earlier (Bourne 1904, Vol, 2:vii).

Rodrigo Ranjel , a conquistador himself, was also the private secretary of Hernando de Soto and was assigned to maintain a daily record of the expedition, therefore, his writings are the closest we can get to a personal journal of Hernando de Soto. As a personal secretary he would have been communicating with Soto on a daily basis throughout the journey through the Southeast. Ranjel never published his notes but they were published by the personal advisor (Oviedo) to the Spanish Crown. Oviedo used the personal Ranjel notes for his publication in 1557. It is thorough and much attention is given to details of Native towns and Chiefdoms names as well as travel dates (Bourne 1904, Vol. 2). Strangely, the Oviedo narrative comes to an abrupt end at a point of the Spanish Expedition sometime after they were west of the Mississippi River.

Garcilaso de la Vega was born in Cuzco, Peru in 1537, the son of a high ranking Spanish officer and an Incan princess. In his youth he knew survivors of the Soto Expedition who had come to Peru to regain their fortunes lost on the expedition. He wrote an intriguing account of the Soto Expedition based on interviews with several Spanish soldiers on the campaign. The informants included Goncalo Silvestre (Bourne 1904, Vol 1:ix), Alons de Carmona and Juan Coles. Though their accounts are brief, they provide valuable details of the Native cultures they encountered. (Varner and Varner 1980, xxiii).

Signature of Biedma

City Street in Elvas, Portugal

Painting of Oviedo

Painting of Vega

The Bay of Ochuse and the Anchorage of the Soto Supply Fleet

At the Soto Expedition’s landing site it was decided that the land army would separate from most of their fleet. The land army would march north into the interior of the Southeast. Most of the fleet was dispatched back to Havana, Cuba to secure supplies for a resupply of the land army when they met later at a harbor on the northern Gulf Coast known as the Bay of Ochuse (Pensacola Bay). The large, deep water bay was located by sailing expeditions ordered by Soto to find a good, later meeting place for a resupply point for the army.

Ranjel wrote that, “…the ships had been dispatched (for supplies) to Havana.” (Bourne 1904, Vol. II1:63).

Elvas wrote that, “ … he also sent the vessels to Cuba at an appointed time, (so) they might return with provisions.” (Bourne 1904, Vol. II1:63).

Image by van Wierngen. Public Domain Image.

Biedma wrote that, “ From this point (Talisi in central Alabama) we went south, drawing towards the coast of New Spain (the Northern Gulf Coast).” (Bourne 1904, Vol II:16).

Biedma also wrote that, “We learned from the Indians that we were as many as forty leagues from the sea (approx. 100 miles). It was much the desire that the governor should go to the coast for we had tidings of the brigantines (the resupply ships) …” (Bourne 1904, Vol II:21). The army wanted to go to their supply ships for sustenance. Soto turned the army north, away from their supply ships perhaps to avoid a mutiny after the ferocious battle at Mabila.

Sixteenth Century Spanish artifacts have been found on Pensacola Bay, perhaps some of which came from trade during the repeated returns of the Soto fleet to the Bay of Ochuse hoping for the rendezvous with their ill-fated mates.

The Journey to Mabila

The Soto army left the Native town and Chiefdom of Talisi in the fall of 1540. Based on archeological and historical data, many archeologists concur that Talisi was located in the area of the lower Tallapoosa River, which is part of the Alabama River drainage in central Alabama, .

Biedma wrote that, “From this point (Talisi) we went south, drawing towards the coast of New Spain

(Gulf of Mexico) …” (Bourne 1904, Vol.1:161). Their supply ships were waiting for them in Pensacola Bay.

The army left Talisi and likely traveled south along the east side of the Alabama River drainage for approximately a week, passing through the Tascaluza Chiefdom, and coming to the Native town of Piachi.

Four of the Spanish chroniclers wrote of the geographic position of Piachi:

Ranjel wrote that the town was,“ … high above the gorge of a mountain stream …”

(Bourne 1904, Vol.2:122);

Elvas wrote that, “… a great river ran near …” (Bourne 1904, Vol.1:89).

Garsilaso wrote that the town was on, “ … the same river that passed through Talisi…” (Varner and Varner 1980:351);

Biedma wrote that the Soto army, “ … came to a river, a copious flood (likely the Alabama River) …”

(Bourne 1904, Vol. 2:17).

Next there is a clue concerning geographical data which may be a major indicator of the area of Mabila. At Piachi, as already stated, the Spanish wrote of elevated terrain. Once they crossed the Alabama River they wrote of traveling into the “montes,” which translates to “little mountains” i.e. a rugged hilly terrain. The army had to camp the night in this hilly wilderness without the benefit of any Native villages because none were found, that being a sparsely Native occupied area.

There are several large Native villages on the east bank of the Alabama River in Monroe County that fit the description of the geographical configuration of Piachi. Archeological research in Clarke County has also supported the Spanish writers. Across the Alabama River from Monroe County is very rough hilly terrain in Clarke county with little to no Mississippian Period sites away from the narrow floodplains of the Alabama and Tombigbee rivers. There are primarily Archaic and Woodland Period hunter-gatherer sites in the region, inhabited thousands of years before the Soto entrada.

There are 22 named mountains in Clarke County, Alabama. It appears that the Spanish chroniclers got it right when describing the terrain on their trip to Mabila when they entered the “Montes” or “little mountains” in Clarke County. After all, some of them on the expedition had seen the huge Sierra Madre mountains in Mexico and the Andes in South America. The rugged terrain of Clarke County would have been seen as “little mountains” to them.

The Arrival at Mabila, the Battle, and Afterwards

The Soto Expedition left the hilly terrain and entered a more level area on their way to Mabila town. They wrote of a “beautiful plain” with rich soil and numerous Native settlements. This hypothesis suggests that the army had passed through the rugged hills of central Clarke County and entered the huge, flat plain of the northern Mobile Delta above the junction of the Alabama River and Tombigbee Rivers. The soils are very rich with alluvial deposits and, consequently, numerous Mississippian Period Native settlements.

Ranjel wrote that, Monday, October 18, St. Luke’s day, the Governor … came to Mabila … (Bourne 1904, Vol. 2:123).

Garcilaso wrote that, The Governor (Soto), who traveled with great caution, came to the town of Mauvila at eight o’clock in the morning … (Mabila was) situated upon a very beautiful plain … (Varner and Varner 1980:353).

Elvas wrote that, The country was a rich soil and well inhabited. Some towns were very large and were picketed (fortified) about. The people were numerous everywhere, the dwellings standing a crossbow shot or two apart. (approx. 100-300 yards) (Bourne 1904, Vol 2:98).

Biedma wrote that, Mabila was, … a small town very strongly stockaded, situated on a plain.

(Bourne 1904:18).

Garcilaso wrote that, … the town of Mauvila was surrounded by a wall as high as three men and constructed of wooden beams as thick as oxen. These beams were driven into the ground so close together that each wedged to the other; and across them on both the outside and inside were laid additional pieces, not so thick but longer, which were bound together with strips of split cane and strong ropes. Plastered over the smaller pieces was a mixture of thick mud tamped down with long straw filling up all of the holes and crevices in the wood and its fastenings, so that, properly speaking, the wall appeared to be coated with a hard finish …

At every fifty feet there was a tower capable of holding seven or eight persons who might fight within it and the lower part of the wall, up to the height of a man, was filled with the embrasures of a battery designed for shooting arrows outside. There were only two gates to the town, one on the east and the other on the west, and in its center there was a great plaza around which were grouped the largest and most prominent houses (Varner and Varner 1980:353-354).

Garcilaso again … there was a great plaza around which were grouped the largest and most prominent houses (Varner and Varner 1980:354).

Garcilaso again, … since the town is small and does not afford sufficient room within for everyone, the rest of his people will remain the distance an arrow shot outside , for there my vassals have constructed them many very fine bowers of branches in which they will be able to lodge themselves pleasantly

(Chief Tascaloosa) (Varner and Varner 1980:354).

Garcilaso also wrote that after the battle, … Our Spaniards spent eight days in the miserable huts that themselves had constructed in Mauvila, but when they were able, they moved into the lodgings previously prepared for them by the Indians, since these places offered more adequate accommodations … Here they remained fifteen additional days to treat the wounded, (Varner and Varner 1980:383).

Elvas wrote that, Because of the wounded, he (Soto) stopped in that place twenty-eight days, all the time remaining out in the fields. (Bourne 1904, Vol. 1:968).

Garcilaso wrote, The Battle ended, Governor Hernando de Soto, in spite of the fact that he himself emerged from the strife badly wounded, took care to order that the dead Spaniards be gathered up so that they might be buried on the following day. (Varner and Varner 1980:374).

The archeological record confirms these statements with the many Mississippian Period archeological sites in the northern Mobile Delta. The sites which include multiple scattered hamlets and occasional larger towns, some with burial mounds. Sixteenth Century Spanish artifacts have also been found in the region.

A river was not mentioned at the town of Mabila but a “pond” was noted. More evidence in support of the hypothesis that the site of Mabila is located in the northern Mobile Delta comes from one of the Spanish chroniclers writing of the day long battle and a nearby “pond”:

Elvas wrote that, The struggle lasted so long that many Christians, weary and very thirsty, went to a pond nearby, tinged with the blood of the killed, and returned to the combat (Bourne 1904, Vol. 1:96).

This “pond” could have been one of the isolated, cutoff river channels located in the northern Mobile Delta region, referred to as “oxbow lakes.” During the heavy rains in winter and spring northern Mobile Delta is regularly flooded, but during the more arid months of fall the region is relative dry, so much so that some of the lakes appear as “ponds.” The Soto Expedition arrived in October, one of the driest months of the entire year.

The battle was furious. Soto and his advance guard of horsemen wanted to enter the town immediately, having spent the previous night camped in the woods. They were further encouraged to do so by the dancing of Native women.

Biedma wrote, Apparently rejoicing, they began their customary songs and dances and some fifteen or twenty women having performed before us a little while … (Bourne 1904, Vol. 2:18).

Those same women later picked up weapons and fought the Spaniards in the battle of Mabila.

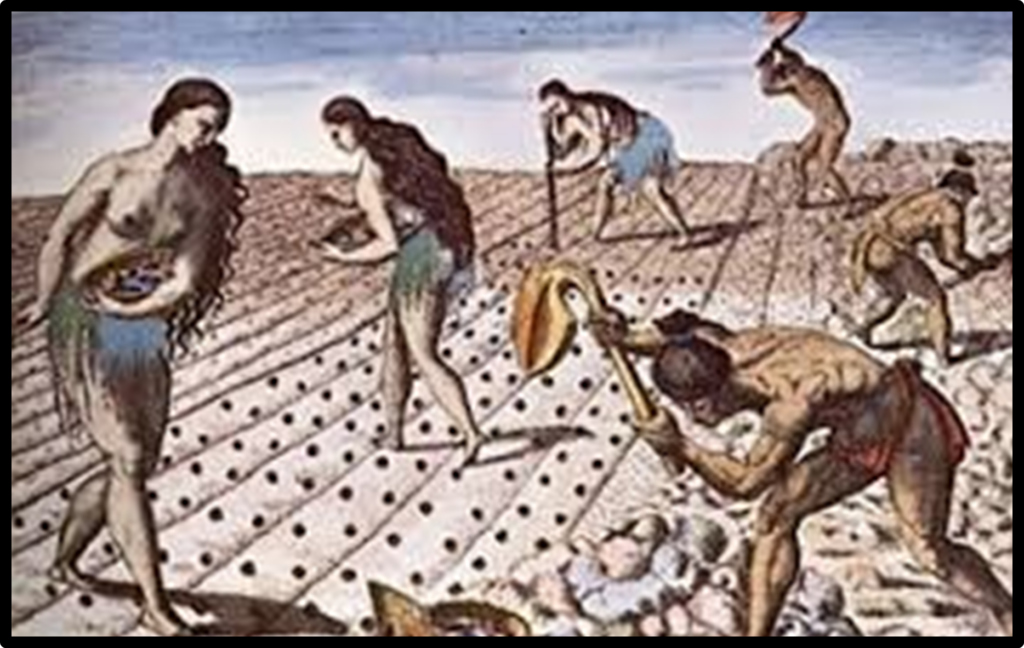

Illustration of Women and Men Planting Fields in the 1500s, Florida Museum of Natural History,Illustration of Women and Men Planting Fields in the 1500s, Florida Museum of Natural History,

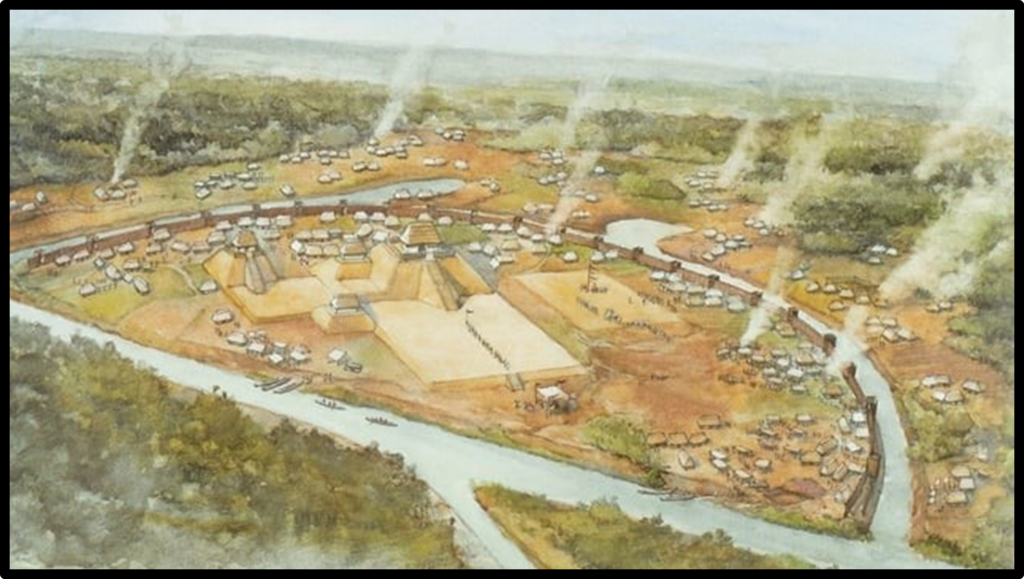

Artist Depiction of a Fortified Native Town. Public Domain Image.

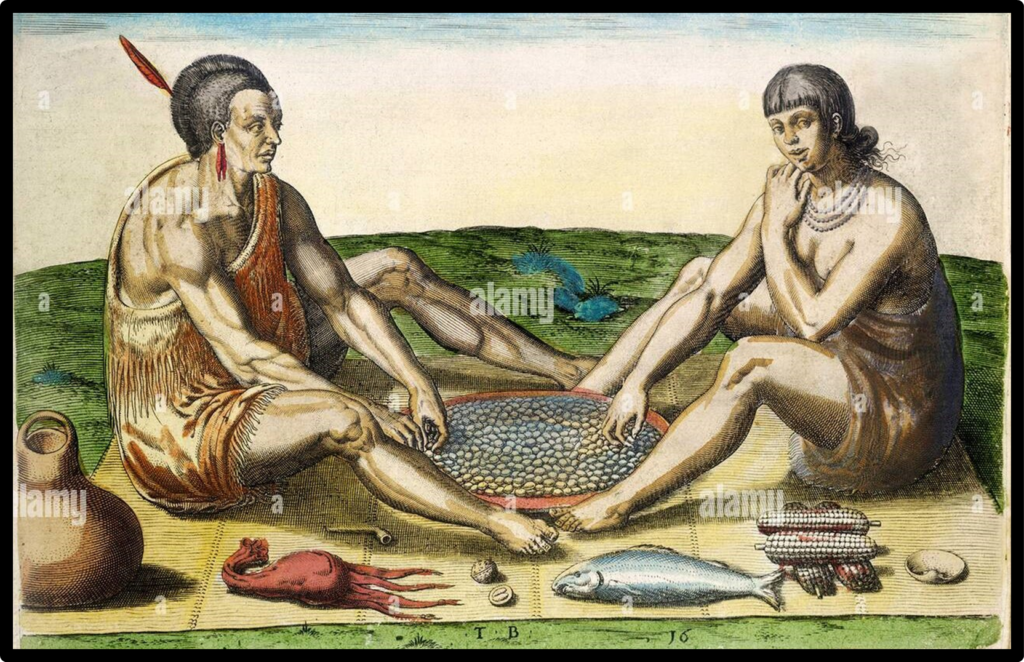

Artist Depiction of a Native Man and Woman preparing Food 1500s.

DeBry and White. Public Domain Image.

The Necessary Archeological Criteria to Identify the Site of Mabila

There is no question that the Soto Expedition left an archeological footprint during their approximate month long stay at the Native town of Mabila. The chroniclers left us with numerous clues as to the description and whereabouts of Mabila, the course of the epic battle and its devastating aftermath. So how does this data translate to the current archeological footprint of Mabila?

- The site should be located on flat ground with rich

- There should be a freshwater pond near the

- It should be a heavily fortified small site with entrances at the east and

- There should not be a river at the

- There should be numerous Native settlements in the area of the

- There should be fire hearths and refuse pit inside and outside the

- There should be Spanish burials in a cemetery

- There should be Native and Spanish artifacts from the

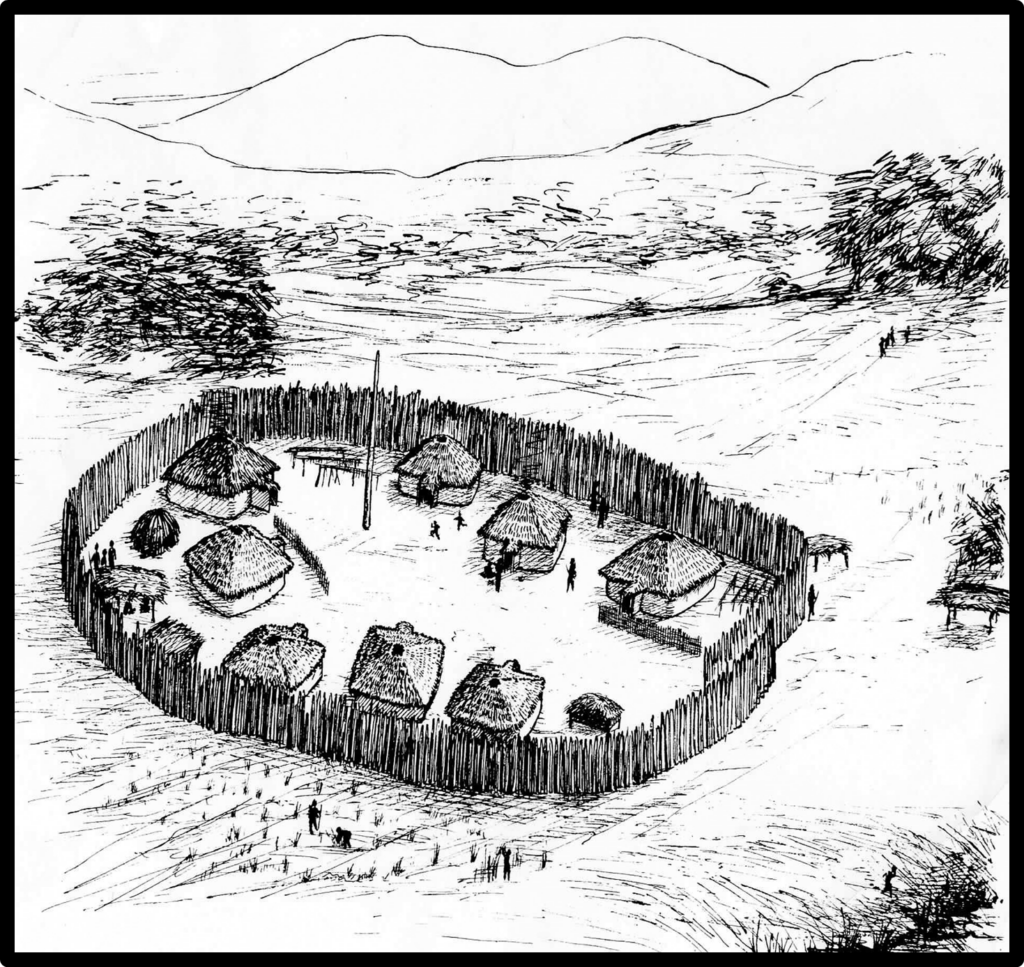

Fortified Native Village of the Mississippian Period. Public domain image.

Examples of Spanish and Native Artifacts from the Mobile Delta in Southwest Alabama.

CAI images.

Historic Documents of the 1700s Provide Possible Evidence of the Location of Mabila

During the 1700s, when the French arrived in the region of the Mobile Delta and Mobile Bay in southeastern Alabama they wrote of the presence of a Native group of people known as the “Mobiliens.” It is not much of a stretch to equate the name “Mobiliens” of the 1700s with the name “Mabilians” of the 1500s. It is important to remember that the Native peoples did not have a written language. The Spanish and French were listening to the Natives speak the names of their towns and doing their best to transpose the sounds of the words to written words, hence, the spellings differed.

There is evidence in the historic European documents and the Native pottery typology that indicate there was a long generational presence in the region during the Mississippian Period. In other words, the Mabila Chiefdom could have been located in the same area in the 1500s that is was in the 1700s.The Mabilians had lived in the southwestern portion of Alabama in the upper and lower Mobile Delta and Bay long before the Soto Expedi- tion arrived in 1540 and even after the Spaniards had left the region in the 1500s and even when the French arrived in the 1700s as indicated by archeological excavations at the Bottle Creek Site (Brown 2003:2; Fuller 2003:32). There are a number of French documents written in 1700s that refer to the Mobiliens. Following are several quotes from translations of some of the documents.

It should even seem, that the Maubilians enjoyed a sort of primacy in religion, over all the other nations in this part of Florida (southwest Alabama); for when any of their fires happened to be extinguished through chance or negligence, it was necessary to kindle them again at theirs (Charlevoix 1977:154, from Knight and Adams 1981).

If this is to be credited, it would seem that the Mobile held a ritual status among the gulf tribes … and that the gulf tribes considered themselves “of one fire.” Such a supposition recalls Iberville’s statement about the then abandoned Mississippian period ceremonial mound center at Bottle Creek, in the heart of the Mobile delta. The site was “the place where the gods are” of which all the nations in the neighborhood tell so many stories and where the Mobilians come to offer sacrifices (likely the Bottle Creek Site, Swanton 1922:161; Hamilton 1910:56; Higginbotham 1977:70).

These (Native) settlements are on islands, this river being full of them for 13 leagues (north of Mobile in the Mobile Delta) … All the land is perfectly fine for settlements. He got an Indian to show him the place where the gods are (likely the Bottle Creek Site) … The gods are brought here. They are five images … a man, a woman, a child, a bear, and an owl … made of plaster in the likeness of the Indians of this country (the statues, presumably ceramic, were taken to France.) (McWilliams 1981:168-169).

The point is that there is strong documental and archeological evidence that the Mabila Chiefdom was a powerful and long lived polity in southwest Alabama when the Soto Army entered its territory in 1540.

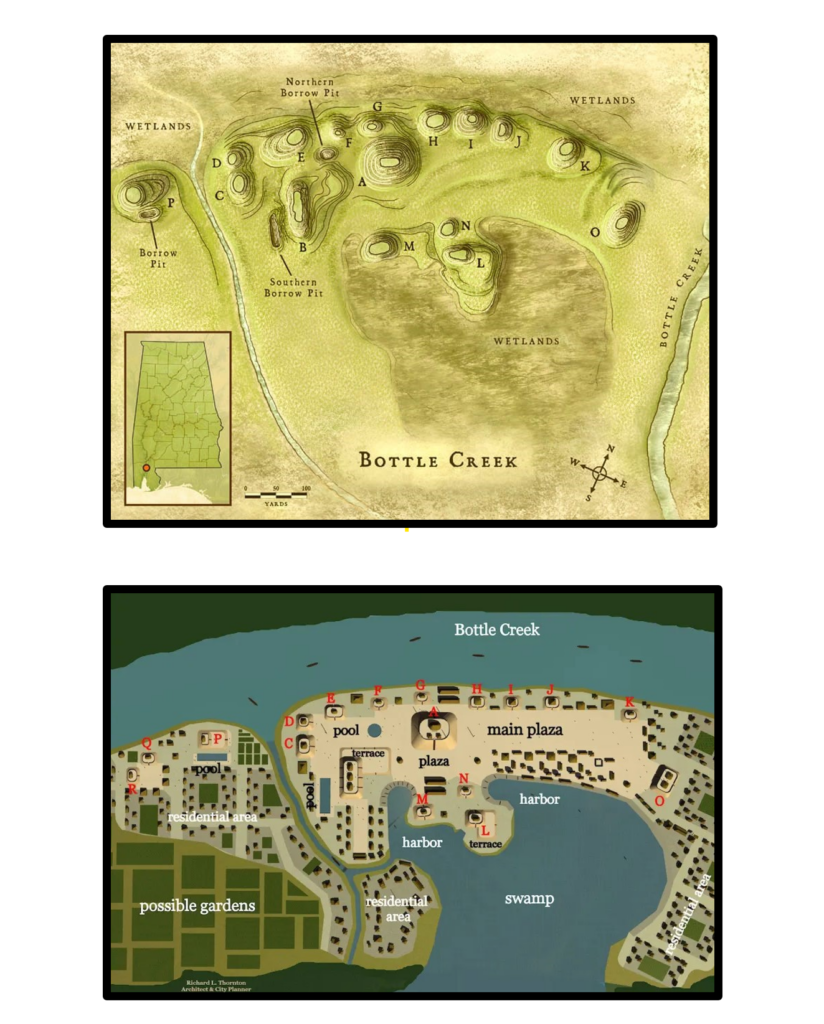

Drawings of the Bottle Creek Ceremonial Complex.

Public Domain Images from Encyclopedia of Alabama and Shipbucket Wiki.

We are certainly not suggesting that the Bottle Creek Site is the battle site of Mabila. We are

hypothesizing that the Bottle Creek Site is the primary ceremonial center of the Mabila Chiefdom and this could indicate that the battle site was at a perimeter town of the chiefdom in the northern portion of the Mobile Delta.

Leaving the Town of Mabila

By November 14, 1540, the Soto army had recovered adequately enough from their wounds and losses to break camp and begin the uncertain trek northward out of the battle-scarred town of Mabila.

Garcilaso wrote, There was almost an infinite number of these minor wounds, for there was scarcely a man among them not injured, and most of them had five and six wounds whereas many had ten and twelve. (Varner and Varner 1980:374).

Garcilaso also wrote, The battle ended, Governor Hernando de Soto, in spite of the fact that he himself emerged from the strife badly wounded, took care to order that the dead Spaniards be gathered up so that they might be buried on the following day. (Varner and Varner 1980:374).

Biedma wrote, This day the Indians slew more than twenty of our men and those of us who escaped only hurt were two hundred and fifty, bearing upon our bodies seven hundred and sixty injuries from their (arrow) shafts. (Bourne 1904 II:21).

Garcilaso wrote, … and to the loss of these men was added that of forty-five horses … (Varner and Varner 1980:377).

Depictions of 16th-Century Spanish and Native combatants in the southern areas of the current United States. (Public Domain Images).

The Journey into the Territory of Pafallaya

Biedma wrote that the army went northward after leaving Mabila, We resumed our direction to the northward

… (Bourne1904 II:21). This was the first directional change reported since Talisi when the chroniclers wrote that they were headed south toward the Gulf of Mexico to meet their resupply ships. The observations they provided us concerning this northward journey is important in support of the hypothesis that the location of Mabila is in southern Clarke County.

Both Ranjel and Biedma wrote that after leaving Mabila the army marched five days through uninhabited territory, likely through the hill country of the physiographic areas of the Lime Hills, Southern Red Hills, Buhrstone Hills, and Chunnenuggee Hills, not a favorable environment for Mississippian Period agriculturists as indicated by archeological surveys (Brose et al 1983; Curren and Majors 1984; Wimberly 1960; Curren

1992; Little and Curren 1990:184; Curren, Caleb, Keith J. Little, and George Lankford III).

The lack of archaeological evidence of Mississippian occupations in this region coincides with the chronicle descriptions of the route north of Mauvila to Pafallaya. A cluster of Mississippian sites in the lower Black Warrior River basin region is postulated as the likely location of Pafallaya (Curren 1989, Little and Curren 1990:184).

No mention was made of a river until they reached the territory of Pafallaya. North of Clarke County is a part of the Tombigbee River drainage known as the Black Warrior River with fertile soils in the floodplains and numerous Mississippian Period and Protohistoric Period sites.

Elvas wrote that after leaving Mabila, the army, marched five days through a wilderness (uninhabited region), arriving in a province called Pafallaya … near which was a large river … Some of the towns were well stored with maize and beans. (Bourne 1904 Vol.1:99).

Elvas wrote that the Natives of Pafallaya and the Spaniards were hostile towards each other, the Indians on the farther bank shouted to the Christians that they would kill them should they come over there (Bourne 1904 Vol. 1:99).

Ranjel wrote that the Spaniards defied the threats, He (Soto) ordered that a piragua be built within the town … (to cross the river). A barge was constructed … and they made a large truck to carry it to (the river, pulled by mules and horses)… and when it was launched in the water sixty soldiers embarked in it (Bourne 1904a:99).

Ranjel wrote that, the Indians were across the river making threats …Hostilities broke out again when the Spanish were crossing the river, The Indians shot countless darts, or rather arrows. But when this great canoe reached the shore they took flight, and not more than three or four Christians were wounded (Bourne 1904 Vol 2:129).

Ranjel wrote that they crossed the river and took the territory, The country was easily secured and they found an abundance of corn (Bourne 1904 Vol.2:99). The Spanish army was in Pafallaya for approximately three weeks (Bourne 1904b:129-130).

The lower Black Warrior was first proposed to be the Pafallaya Chiefdom in the 1980s and again in the 1990s. It was suggested that more archeological research was needed, particularly in Marengo and Hale Counties, The river of Apafalaya (Pafallaya) that the army crossed is the present–day Warrior River. The actual crossing place was, generally, between present-day Demopolis in Marengo County and the Warrior Lock and Dam upstream in Hale County … This region needs more archeological investigation …

(Curren 1987:49).

Current Archeological Investigations in the Lower Warrior River Basin

Thirty-seven years after the original hypothesis that Pafallaya is located in the lower Warrior River drainage Basin and the call for more archeological research, that research has finally begun.

The University of West Alabama (UWA) has discovered numerous 16th Century Spanish artifacts in Marengo and Hale Counties in the lower Warrior River drainage. UWA is using large numbers of people for metal detector sweeps of plowed fields for artifact recovery.

Spanish artifacts have been found with … metal detection, a technology long stigmatized due to its association with relic-hunting (van Hoose 2024:4).

UWA has suggested several possible sources of the artifacts but lean towards the battle of Mabila (Knight, Vernon J. and Neal Lineback 2019) (Vernon J. Knight and Ashley A. Dumas 2024). The proposed sources of the Spanish artifacts include: objects retrieved from the battle of Mabila or Chicaza, or even objects from the 1559 Tristan de Luna Expedition. The Spanish presence in Pafallaya was not included as a source of the artifacts. It certainly should be part of the equation concerning the source of the Spanish artifacts. It is hoped that UWA will continue their important research in the lower Warrior River drainage.

Lower Black Warrior River.

Public Domain Image.

The Territory of the Chicasa

The Spanish kidnapped the chief of Pafallaya to assure their safe passage through his territory and spent some 5-6 days traveling northward before arriving at the River of Chicasa. They had entered a new territory, the Chiefdom of Chicasa.

Ranjel wrote that from Pafallaya, the Governor and his army set out in search of Chicaca on Thursday, December 9. The following Tuesday they arrived at the river of Chicaca, having traversed many bad passages and swamps and cold rivers (Bourne 1904, Vol. II:130).

Elvas wrote that, Thence towards Chicaca the Governor marched five days through a desert (an uninhabited region) and arrived at a river (Bourne 1904, Vol. I:100). He crossed the river the seventeenth of December, and arrived the same day at Chicaca, a small town of twenty houses (Bourne 1904, Vol. I:100).

Biedma omitted Pafallaya and recorded the trip direct from Mabila to Chicasa. Biedma wrote that, We resumed our direction to the northward and traveled ten or twelve days suffering greatly from the cold and rain, in which we marched afoot, until arriving at a fertile province (Chicasa), plentiful in provisions, where we could stop during the rigour of the (winter) season (Bourne 1904, Vol. II:21).

The Native people resisted the Spanish army most of time they were in Chicasa and attacked them repeatedly through the winter months. Many night attacks ensued during the Spanish army stay in Chicaza. The attacks came close to putting an end to the Soto Expedition (Bourne 1904 vol. 2:104-105) (Varner and Varner 1980:399) ( Bourne 1904, Vol. II:22-23).

The Spanish army left Chicasa in the spring of 1541 and headed west to more adventures, contacts with more Native people, and death. The survivors finally made it to Mexico City. They were unrecognizable to their own people, having traversed thousands of miles of hostile, harsh territory. They were bearded, bedraggled, and exhausted. Once recognized they were honored for their long journey. They had originally been looking for treasure and land to claim for Spain. As it turned out, they did bring back treasure … the first extensive written accounts of the interior Native people of the Southeast.

Illustration of the Battle of Chicaza.

Public Domain Image.

The “Official” Mabila Location

A trail of the Soto Expedition has been “governmentally officially” designated through the Southeast. The trail depicts Mabila near Selma, Alabama although there is no evidence to support this claim. Unfortunately, now the alleged Soto route appears as irrefutable fact in textbooks, websites, road signs, and many current maps. It is based on academic politics — not scientific facts.

This “official” Soto trail is largely acknowledged due to publications by the Alabama De Soto Commission and the National Park Service (De Soto National Trail Study, Final Report Prepared by the De Soto National Trail Act of 1987, National Park Service Southeast Regional Office, March 1990) (The Alabama De Soto Commission Working Paper Series, Published by the University of Alabama).

Both groups failed to give the public their due of hard core scientific investigations and facts. Politics overrode scientific data. As a former commissioner of the Alabama De Soto Commission I can attest to the controversy surrounding this premature conclusion.

Dr. John R. Swanton was an eminent scholar affiliated with the Smithsonian Institution and a prominent early researcher of the Soto Expedition route (Swanton 1939). He perfectly synopsized the current situation relative to the Soto route through south Alabama and the location of Battle Site of Mabila.

Nothing is made correct because it is called “Official.”

(Quote from John R. Swanton from Sturtevant 1985).

Dr. John R. Swanton, 1843-1958.

Public Domain Image.

General Summary

The archeological and historical importance of the location of the Native town and battle site of Mabila has been presented in this article. Excerpts from the chroniclers of the Soto Expedition have been presented as has the error of premature Soto route claims being announced and publicized by various universities and governmental agencies.

Quotes from the Soto chroniclers corroborated by archeological data and terrain observations have also been compared in this article. A “Related Archeological and Historical Sources” section is also provided to readers who wish to delve into more details of the hypotheses of this incredible journey and the historic meeting of two cultures.

Our current hypothesis is based on the primary source documents of the Spanish chroniclers, archeological research, and geographic terrain. The conclusion is that the most promising region for the Native town and battle site of Mabila is located in the upper Mobile Delta “Forks” region of southern Clarke County, Alabama.

The basic concept of this hypothesis is straightforward. As we have written and stated for decades, it stands to reason that the places the Soto army stayed the longest would have the largest number of their artifacts left there through trade or battle artifacts garnered by the Natives.

The focus of the section of the Soto route through Alabama that is addressed in this article are the Chiefdoms of Talisi, Mabila, Pafallaya and Chicaza. The highest concentration of late Mississippian Period Native sites and 16th Century Spanish artifacts in these areas are the junctions of the Tallapoosa, Coosa, and Alabama Rivers (Talisi), the Forks region of southern Clarke County (Mabila), and the upper Tombigbee River drainage (Pafallaya and Chicasa).

Contact Archeology Inc. (CAI) through grants, volunteers, information from local people, and landowner permission is continuing to test this hypothesis using Spanish documents, topographic maps, LIDAR imagery, satellite maps, remote sensing, and basic hand dug, screened shovel excavations. We plan to present updates of our research on our online Research Journal (archeologyink.com).

One of the hypotheses of the Mabila site location has held up to scientific scrutiny without any rash claims, that being the “Forks” of southern Clarke County. Although the Mabila site has not been found, the region seems to be the closest fit to what the Spanish chroniclers of the Soto Expedition described geographically.

Archeological research in Clarke County has fortified the hypothesis that Mabila was in the southern portion of the county.

We continue our search.

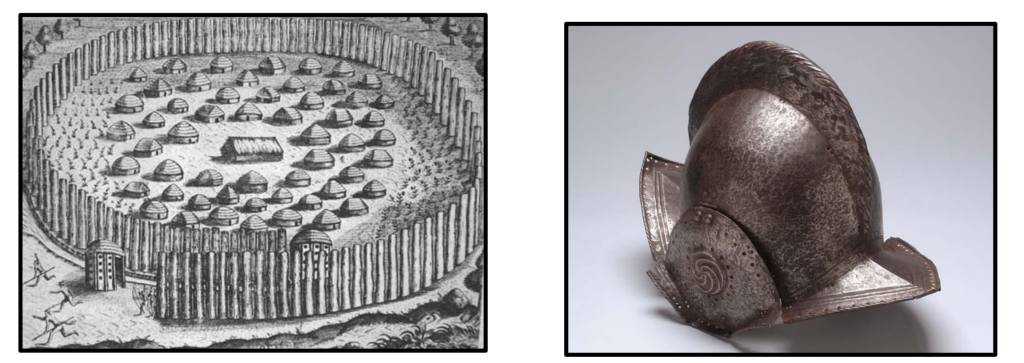

Illustrations of a fortified 16th-Century Native village and a Spanish helmet of the period.

Public Domain Images.

A Sample of Related Archeological and Historical Sources

Atkinson, J.R.

1979 A Historic Contact Indian Settlement in Oktibbeha County, Mississippi. Journal of Alabama Archeology 25(1):61-82.

1987 The DeSoto Expedition Through North Mississippi. Mississippi Archaeology 22(1):61-73.

1987 Historic Chickasaw Cultural Material: A More Comprehensive Identification. Mississippi Archaeology 22(2):32-62.

Atchinson, Robert B., Jr.

1987 Archaeological Survey in the Lower Cahaba Drainage. Report of Investigations 53. University of Alabama Office of Archaeological Research, Moundville.

Ball, T.H.

1978 A Glance into the Great Southeast. or Clarke County. Alabama and its Surroundings from 1540 to 1877. Reprinted by Clarke County Historical Society from the 1882 original.

Bigelow, A.

1851 Observations on Some Mounds on the Tensaw River. American Journal of Science, Article XXI, Vol. 65.

Blake, Allan

1987 A Proposed Route of the Hernando de Soto Expedition Based on Physiography and Geology. Alabama De Soto Commission Working Papers 2,4,6.

1988 Legua Legal or Legua Comun: A Discussion. Alabama De Soto Commission Working Paper 5.

Bourne, Edward Gaylord

1904 Narratives of the Career of Hernando de Soto. The Trail Makers Series, A.S. Barnes and Company. New York. (2 volumes.)

Brain, Jeffrey P.

1975 Artifacts of the Adelantado. Conference on Historic Site Archaeology Papers 8:129-135. Columbia, South Carolina.

1985 Archaeology of the Hernando de Soto Expedition. in Alabama and the Borderlands. Badger, Reid and Lawerence Clayton, ed. University of Alabama Press, University, Alabama.

1985 Introduction to Final Report of the United States De Soto Expedition Commission, by John R. Swanton, Smithsonian Classics of Anthropology, Washington D.C., Reprinted from the 1939 original.

Brannon, Peter A.

1920 Handbook of the Alabama Anthropological Society. Publications of the Alabama State. Department of Archives and History.

1938 Urn Burial in Central Alabama. American Antiquity 13.

Brock, Oscar W. Jr., Richard S. Fuller and Stephen C. Law

1978 Archaeological investigations at the Ideal Basic Industries. Inc. Perdue Hill Ouarrv Site. Monroe County, Alabama. Report to Environmental Science and Engineering, Inc., from the University of South Alabama.

Brockington and Associates, Inc.

1997 Cultural Resources Reconnaissance of the Lower Alabama River Study Area, Baldwin, Monroe, and Clarke Counties, Alabama. Submitted to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Mobile District.

Brown, Ian W. (ed)

2003 Bottle Creek; A Pensacola Culture Site in South Alabama. The University of Alabama Press.

2009 An Archaeological Survey in Clarke County, Alabama. The Alabama Museum of Natural History, Bulletin 26, January 15.

Brooms, B. MacDonald and James W. Parker

1980 Fort Toulouse Phase Ill Completion Report. Alabama Historical Commission and the Heritage. Conservation and Recreation Service.

1980 Fort Toulouse Phase IV Progress Report. Alabama Historical Commission and the Heritage. Conservation and Recreation Service.

Brose, David S., Ned J. Jenkins, and Russell Weisman

1983 Cultural Resources Reconnaissance Study of the Black Warrior Tombigbee System Corridor. Alabama, Vol. I. Archaeology. Report to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Mobile District from the University of South Alabama.

Burke, R.P.

1930 Ceramics of the D River, Part V. Arrow Points (2). 1930 Urns of the D River. Arrow Points 17(4).

1936 Check List of Indian Glass Trade Beads. Arrow Points 21(5-6). Montgomery, Alabama.

Chardon, Roland

1980 The Elusive Spanish League: A Problem of Measurement in Sixteenth-Century New Spain. The Hispanic American Historical Review 60(2):294-302.

Charlevoix, Pierre Francois Xavier de

1977 Charlevoix’s Louisiana. Selections from the History and the Journal. C.E. O’Neal, ed. Louisiana State University Press. Baton Rouge.

Chase, David

1967 Fort Toulouse, First Investigations, 1966. Conference on Historic Site Archaeology Papers, 2(1): 33-49.

1979 A Brief Synopsis of Central Alabama Prehistorv. Paper presented at the winter meeting of the Alabama Archaeological Society.

1983 Site 1Ds53: A Glimpse of Central Alabama Prehistory from the Archaic Period to the Historic Period. In Archaeology in Southwestern Alabama. Edited by Caleb Curren. Alabama-Tombigbee Regional Commission. Camden, Alabama.

Contact Archeology Inc. An Online Research Journal (archeologyink.com).

2022 The Battle Site of Mabila ? A Critique of the University of West Alabama Claim.

2018 A Queen’s Pearl from the Lower Alabama River? An Online Research Journal (archeologyink.com).

2018 Mabila: The Largest Battle Ever Fought Between Europeans and Natives on American Soil. An Online Research Journal (archeologyink.com).

2014 Pine Log, an Extraordinary Spanish/Native Contact Site. An Online Research Journal (archeologyink.com). 2009 First Contact Spanish Artifacts. An Online Research Journal (archeologyink.com).

2009 Rolling Hills, an Important Spanish Contact Site. An Online Research Journal (archeologyink.com).

Cottier, John W.

1968 Archaeological Salvage Investigations in the Millers Ferry Lock and Dam Reservoir. Report to the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service from The University of Alabama.

1970 The Alabama River Phase: A Brief Description of a Late Phase in the Prehistory of South Central Alabama. On file at the Department of Anthropology, The University of Alabama.

Cottier, John W. and Craig T. Sheldon

1980 Interim Report of an Archaeological Survey of U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Properties along the Alabama River. Report to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Mobile District from Auburn University.

Crosby, Alfred W. Jr.

1972 The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492. Greenwood Press. Westport, Connecticut.

Cumming, William P.

1958 The Southeast in Early Maps. Princeton University Press. Princeton, New Jersey.

Curren, Caleb

1976 Notes on Brief Archaeological Examination of Tuscaloosa County Alabama. Report on file at Mound State Monument, Moundville, Alabama.

1976 Prehistoric and Early Historic Occupation of the Mobile Bay and Mobile Delta Area of Alabama with an Emphasis on Subsistence. Journal of Alabama Archaeology 22(1).

1982 Salt Processing Sites in Southwest Alabama. in, Archaeology in Southwest Alabama: A Collection of Papers. Alabama-Tombigbee Regional Commission. Camden, Alabama.

1982 The Alabama River Phase: A Review, in, Archaeology in Southwest Alabama: A Collection of Papers. Alabama-Tombigbee Regional Commission. Camden, Alabama.

1984 The Protohistoric Period in Central Alabama. Alabama-Tombigbee Regional Commission. Camden, Alabama.

1986 An Archaeological Reconnaissance of Choctaw. Washington. And Southern Clarke Counties in

Southwest Alabama. Report to the Alabama Historical Commission from the Alabama-Tombigbee Regional Commission.

1986 In Search of De Soto’s Trail. Alabama-Tombigbee Regional Commission. Bulletins of Discovery1, Camden, Alabama. 1987 The Route of the Soto Army Through Alabama. Alabama De Soto Commission Working Paper Series 3.

1988 A Rebuttal of the “Georgia Reconstruction” of the Soto Route Through Alabama. Report submitted to the Alabama De Soto Commission.

1991 Spades Are Trumps. The Soto States Anthropologist 91(1):39-44.

2017 The Battle of Mabila: Recent Archeological Testing in the “Forks.” An Online Journal (archeologyink.com).

Curren, Caleb and Mark Curl

1985 An Archaeological Reconnaissance of Wilcox, and Dallas Counties in Southwest Alabama.

Report submitted to the Alabama Historical Commission from the Alabama-Tombigbee Regional Commission.

1982 The Alabama River Phase: A Review, in, Archaeology in Southwest Alabama: A Collection of Papers. Alabama-Tombigbee Regional Commission. Camden, Alabama.

1984 The Protohistoric Period in Central Alabama. Alabama-Tombigbee Regional Commission. Camden, Alabama.

1986 An Archaeological Reconnaissance of Choctaw. Washington. And Southern Clarke Counties in

Southwest Alabama. Report to the Alabama Historical Commission from the Alabama-Tombigbee Regional Commission.

1986 In Search of De Soto’s Trail. Alabama-Tombigbee Regional Commission. Bulletins of Discovery #1, Camden, Alabama. 1987 The Route of the Soto Army Through Alabama. Alabama De Soto Commission Working Paper Series 3.

1988 A Rebuttal of the “Georgia Reconstruction” of the Soto Route Through Alabama. Report submitted to the Alabama De Soto Commission.

1991 Spades Are Trumps. The Soto States Anthropologist 91(1):39-44.

Curren, Caleb and Mark Curl

1985 An Archaeological Reconnaissance of Wilcox, and Dallas Counties in Southwest Alabama.

Report submitted to the Alabama Historical Commission from the Alabama-Tombigbee Regional Commission.

Curren, Caleb, George Lankford, and Gregory Spies

1971 Progress Reports 1-2 of an Archaeological Site Survey of South Alabama. Report to the Archaeological Research Association of Alabama, Inc. from the University of South Alabama.

Curren, Caleb, Keith J. Little, and George E. Lankford, Ill

1981 The Route of the Expedition of Hernando de Soto Through Alabama. Paper presented at the 38th

Annual Meeting of the Southeastern Archaeological Conference, Nov. 12-14, 1981. Asheville, North Carolina.

1982 Archaeological Research Concerning Sixteenth Century Spanish and Indians in Alabama. Report on file at the Alabama-Tombigbee Regional Commission.

Curren, Caleb and Janet Lloyd

1987 Archeological Survey in Southwest Alabama: 1984-1987. Alabama-Tombigbee Regional Commission Technical Report 1.

Curren, Caleb and Lee McKenzie

1988 Archaeological Investigations at Three Sites in the “Mauvila Province.” Report to the Alabama Historical Commission from the Alabama-Tombigbee Commission.

Curren, Caleb and Rhonda Majors

1984 An Archaeological Reconnaissance of Monroe and Clarke Counties in Southwest Alabama.

Report submitted to the Alabama Historical Commission from Alabama-Tombigbee Regional Commission.

Curren, Caleb and Noel R. Stowe

1974 Progress Reports 1-2 of an Archaeological Site Survey of South Alabama. Report to the Archaeological Research Association of Alabama Inc. from the University of South Alabama.

Curren, Caleb, Keith J. Little, and Harry 0. Holstein

1989 Aboriginal Societies Encountered by the Tristan de Luna Expedition. The Florida Anthropologist 42(4):38 1-395.

Deagan, Kathleen A.

1979 The Material Assemblage of 16th Century Spanish Florida. Historical Archaeology 12:25-50.

1980 Spanish St. Augustine: America’s First “Melting Pot”. Archaeology 33(5):22-30.

1981 Downtown Survey: The Discovery of Sixteenth Century St. Augustine in an Urban Area. American Antiquity 46(3):626-634.

DeJarnette, David L

1975 Highway Salvage Excavations at two French Colonial Period Indian Sites on Mobile Bay, Alabama. Report to the Alabama Highway Department from The University of Alabama.

DePratter, Chester, Charles Hudson, and Marvin Smith

1985 The Hernando de Soto Expedition: From Chiaha to Mabila. in, Alabama and its Borderlands,

from Prehistorv to Statehood. R. Badger and L.A. Clayton editors. University of Alabama Press, University, Alabama.

Dickens, Roy S. Jr.

1971 Archaeology in the Jones Bluff Reservoir of central Alabama. Journal of Alabama Archaeology 17(1):3-102.

Dobyns, Henry F

1983 Their Number Became Thinned: Native American Population Dynamics in Eastern North America. University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville, Tennessee.

Dodson, David

2022 Aztec or Native? The Mystery of the Red Pottery at the Alleged 1559 Luna Colony Site. Contact Archeology Inc., An Online Journal.

2021 Fact, Fiction, or Fraud? The University of West Florida and the “Irrefutable” 1559 Luna Settlement Site.

Contact Archeology Inc., An Online Journal.

Contact Archeology Inc., An Online Journal.

2018 The First Latrines and Privies. Contact Archeology Inc., An Online Journal.

Eubanks, W.S. Jr.

1990 Swanton: Four…. Hudson: Zero. The Soto States Anthropologist 90(1):3-32.

1991a Artifacts and Spanish Explorers. The Soto States Anthropologist 91(1):86-92. 1991b De Soto, Still Another Look. The Soto States Anthropologist 91(2):149-190.

Finlay, Louis M. Jr.

1991 The Syphrit Coin. Clarke County Historical Society Quarterly 16(2):8-12.

Eubanks, W.S. Jr.

1990 Swanton: Four…. Hudson: Zero. The Soto States Anthropologist 90(1):3-32.

1991 Artifacts and Spanish Explorers. The Soto States Anthropologist 91(1):86-92. 1991 De Soto, Still Another Look. The Soto States Anthropologist 91(2):149-190.

Finlay, Louis M. Jr.

1991 The Syphrit Coin. Clarke County Historical Society Quarterly 16(2):8-12.

Fuller, Richard S.

1985 The Bear Point Phase of the Pensacola Variant: The Protohistoric Period in Southwest Alabama. The Florida Anthropologist 38:1-2.

2003 Out of the Moundville Shadow, The Origin and Evolution of Pensacola Culture. In Bottle Creek , A Pensacola Culture Site in South Alabama edited by Ian Brown 2003, University of Alabama Press.

Fuller, Richard S. and Noel R. Stowe

1982 A Proposed Typology for Late Shell Tempered Ceramics in the Mobile Bay / Mobile-Tensaw Delta Region. In, Archeology in Southwest Alabama: A Collection of Papers. Caleb Curren

(ed.). Alabama-Tombigbee Regional Commission. Camden, Alabama.

Fuller, Richard S., Diane E. Silvia, and N.R. Stowe

1984 The Forks Project: An Investigation of the Late Prehistoric-Early Historic Transition in the Alabama-

Tombigbee Confluence Basin. Report submitted to the Alabama Historical Commission from The University of Alabama.

Graham, J. Bennett

1967 A Preliminary Report of Salvage Archaeology in the Claiborne L Dam Reservoir. Report to the National Park Service from the University of Alabama Department of Anthropology.

Gresham, Thomas H., Karen Wood, Jerald Ladbetter, Chad Braley, and Paul Gradner

1987 Archaeological Testing at 1Mn30 Eureka Landing, Monroe County, Alabama. Report from Southeastern Archaeological Services to U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Hamilton, Peter J.

1976 Colonial Mobile. Reprinted from the 1910 original. University of Alabama Press, University, Alabama.

Hayward, Hampton Dart, Caleb Curren, Ned J. Jenkins, and Keith J. Little

1990 Archeological Investigations in the Proposed Pafallaya Province. Report Submitted to the Alabama De Soto Commission.

Higginbotham, Jay

1966 The Mobile Indians. Mobile, Alabama.

Hill, Mary C.

1979 The Alabama River phase: A Biological Synthesis and Interpretation. M.S. thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Tennessee.

Holmes, Nicholas H., Jr.

1963 The Site on Bottle Creek. Journal of Alabama Archaeology 9(1). University, Alabama.

Hudson, Charles

1987 The Uses of Evidence in Reconstructing the Route of the Hernando de Soto Expedition. Alabama De Soto Commission Working Paper Series 1. University.

1987 An Unknown South: Spanish Explorers and Southeastern Chiefdoms. In Visions and Revisions:

Ethnohistoric Perspectives on Southern Cultures, G. Sabo and W.M. Schneider (eds). Southern Anthropological Society. Proceedings 20. University of Georgia Press, Athens.

1988 Critique of Caleb Curren’s De Soto Route. Report Submitted to the Alabama De Soto Commission.

1990 A Synopsis of the Hernando De Soto Expedition, 1539-1545. De Soto Trail National Historic Trail Study. Final Report. Wink Hastings (ed). National Park Service Southeast Region. Atlanta.

Hudson, Charles, Marvin Smith, and Chester DePratter

1987 The Hernando De Soto Expedition: From Mabila to the Mississippi River. Updated paper presented at the symposium “Towns and Temples Along the Mississippi,” Memphis State University, October 18, 1985.

Hudson, Charles and Marvin Smith

1990 Reply to Eubanks. The Florida Anthropologist 43(1):36-42.

Jenkins, Ned J. Jr.

2009 The Village of Mabila: Archeological Expectations. (In) The Search for Mabila. The University of Alabama Press.

Jenkins, Ned J. Jr., Caleb Curren, and Mark F. DeLeon

1975 Archaeological Site Survey of the Demopolis and Gainesville Lake Navigation Channels and Additional Construction Areas. Report to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Mobile District from the University of Alabama.

Jenkins, Ned J., and Teresa Paglione

1980 An Archaeological Reconnaissance of the Lower Alabama River. Report to the Alabama Historical Commission from Auburn University.

1983 Lower Alabama River Ceramic Chronology: A Tentative Assessment. In, Archaeology in South

western Alabama: A Collection of Papers. edited by Caleb Curren. Alabama-Tombigbee Regional Commission. Camden, Alabama.

Jenkins, Ned J. and Craig T. Shelton

2016 Late Mississippian / Protohistoric Ceramic Chronology and Cultural Change in the Lower Tallapoosa and Alabama River Valleys. Journal of Alabama Archaeology.

2020 The Hernando de Soto and Tristan de Luna Expeditions in Central Alabama. In Modeling Entradas: Sixteenth-Century: Assemblages in North America. Edited by Clay Mathers. University of Florida Press.

Jeter, Marvin D.

1973 An Archaeological Survey in the Area East of Selma. Alabama. 197 1-1972. Report to the Alabama Historical Commission from the University of Alabama Birmingham.

Johnson, J.K., P.K. Galloway, and W. Belokon

1989 Historic Chickasaw Settlement Patterns in Lee County, Mississippi: A First Approximation. Mississippi Archeology 24(2):45-52.

Johnson, J.K. and G.R. Lehmann

1990 Sociopolitical Devolution in Northeast Mississippi and the liming of the De Soto Entrada. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists, Miami, Florida.

Johnson, Jay, Geoffrey Lehmann, James Atkinson, Susan Scott, and Adrea Shea

1991 Protohistoric Chickasaw Settlement Patterns and the De Soto Route in Northeast Mississippi: Final Report. Report to the National Endowment for the Humanities and National Geographic Society from University of Mississippi Center for Archaeological Research.

Johnson, J.K. and J.T. Sparks

1986 Protohistoric Settlement Patterns in Northeastern Mississippi. In The Protohistoric Period in theMid-South: Proceedings of the 1983 Mid-South Archaeological Conference. David H. Dye and R.C. Brister (eds). Mississippi Department of Archives and History Archaeological Report.

Kjeldgaard, Linda L. (ed.)

1987 Possible Coronado Campsite Discovered in New Mexico. Encuentro. A Columbian Quincentenary Newsletter 2(3). Winter,1987. University of New Mexico. Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Knight, Vernon J., Jr.

1977 The Mobile Bay-Mobile River Delta Region: Archaeological Status Report. Journal of Alabama Archaeology 23(2).

1987 A Report of Alabama DeSoto Commission/Alabama State Museum of Natural History Archaeological Test Excavations at the Site of Old Cahawba. Dallas County. Alabama. Report to the Alabama DeSoto Commission from the University of Alabama Museum of Natural History.

1988 A Summary of Alabama’s De Soto Mapping Project and Project Bibliography. Report to the Alabama De Soto Commission from the University of Alabama Museum of Natural History.

Knight, Vernon James, Jr., and Sheree L. Adams

1981 A Voyage to the Mobile and Tomeh in 1700, with Notes on the Interior of Alabama. Ethnohistory 28(2): 179-194.

Knight, Vernon James, Jr. and Ashley A. Dumas

2024 Sixteenth-century European Metal Artifacts from the Marengo Complex, Alabama. Southeastern Archaeologist.

Lankford, George E., III

1977 A New Look at De Soto’s Route through Alabama. Journal of Alabama Archaeology 23(1): 10-36.

1983 A Documentary Study of Native American Life in the Lower Tombigbee Valley. In Cultural Resources

Reconnaissance Study of the Black Warrior- Tombigbee System Corridor Alabama. Vol.II, Ethnohistory. Report to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Mobile District from the University of South Alabama.

Little, Keith J.

1988 A Critical Evaluation of the Proposed Locality of Mauvila in the Selma, Alabama Vicinity. Submitted to the Alabama De Soto Commission.

1988 A Critical Evaluation of the Hudson and Associates Use of Distance Statistics. Submitted to the Alabama De Soto Commission.

1988 The De Soto Route Debates: A Presentation for the General Public. Bulletins of Discovery 2. Alabama-Tombigbee Regional Commission. Camden, Alabama.

Little, Keith J., and Caleb Curren

1990 Conquest Archaeology of Alabama. In Archaeological and Historical Perspectives on the Spanish Borderlands East, Columbian Consequences 2, David Hurst Thomas (ed). Smithsonian Institution Press.

1990 The Alabama De Soto Commission Debates: A Reply to the Criticisms of Charles Hudson. The Florida Anthropologist 90(2):87-88.

1990 Contemporary Politics of Sixteenth Century Spanish Explorations. The Soto States Anthropologist 90(2):87-89.

Little, Keith J., Caleb Curren and Lee McKenzie

1988 A Preliminary Archaeological Survey of the Perdido Drainage, Escambia County, Florida. University of West Florida Report of Investigation 20. Pensacola.

1988 A Preliminary Archaeological Survey of the Perdido Drainage, Baldwin and Escambia Counties, Alabama. Alabama-Tombigbee Regional Commission Technical Report 2. Camden.

Little, Keith J. and Kevin Harrelson

2005 Pine Log Creek, Ethnohistoric Archaeology in the Alabama-Tombigbee Confluence Basin. Jacksonville State University Archaeological Laboratory, Research Series Number 3.

Little, Keith J. and Hunter B. Johnson

2018 Ceramic Modes and Protohistoric Population Movements. Papers in honor of Richard A. Krause at the 2018 annual meeting of the Southeastern Archaeological Conference, Augusta, Georgia.

Legg, James B., Charles R. Cobb, Edmond A. Boudreaux III, Brad R. Lieb, Chester DePratter, and Steven D. Smith

2020 The Stark Farm Site Enigma: Evidence of the Chicasa (Chikasha)-Soto Encounter in Mississippi. In Modeling Entradas: Sixteenth-Century: Assemblages in North America. Edited by Clay Mathers. University of Florida Press.

Lowery, Woodbury

1959 The Spanish Settlements Within the Present Limits of the United States. 1513-1561. Russell and Russell, Inc. New York, New York.

Martin, Troy 0.

1989 Archaeological Investigations of an Aboriginal Defensive Ditch at Site 1Ds32. Journal of AlabamaArchaeology 35(1):60-74.

Marshall, Richard A.

1977 Lyon’s Bluff Site (220K!) Radiocarbon Dated. Journal of Alabama Archaeology 23(1):53-58.

1986 The Protohistoric Component at the Lyon’s Bluff Site Complex, Oktibbeha County, Mississippi. In The Protohistoric Period in the Mid-South: 1500-1700. David H. Dye and R.C. Brister (eds). Mississippi Department of Archives and History Archaeological Report 18.

McWilliams, Richebourg G. (ed.)

1981 Iberville’s Gulf Journals. University of Alabama Press. University, Alabama.

Mikell, Gregory A. and Keith J. Little

1999 An Archaeological Investigation of the Doctor Lake Site (1Ck219): A Search for the Sixteenth-Century Mabila Battlefied.

Panamerican Consultants, Inc.

Moore, Clarence B.

1899 Certain Aboriginal Remains of the Alabama River. Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 11 (4):289-347.

1901 Certain Aboriginal Remains of the Tombigbee River. Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 13.

1904 Aboriginal Urn-burial in the United States. American Anthropologist 6:660-669.

1905 Certain Aboriginal Remains of the Black Warrior River. Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 13 (2):145-244.

1905 Certain Aboriginal Remains of the Lower Tombigbee River. Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 13(2):245-276.

Nance, C. Roger

1976 The Archaeological Sequence at Durant Bend, Dallas County, Alabama. Alabama Archaeological Society. Special Publication 2.

National Park Service

1990 De Soto National Trail Study Final Report. Prepared as required by the De Soto National Trail Study Act of 1987. National Park Service, Southeast Regional Office.

Nielsen, Jerry J

1976 Archaeological Salvage Excavations at Site 1Au28. Journal of Alabama Archaeology 22(2). Nielsen, Jerry J., N.J. Jenkins, W.J. Anderson, and B. Bizzoco.

Nielsen, Jerry, John W. O’Hear, and Charles W. Moorehead

1973 An Archaeological Survey of Hale and Green Counties, Alabama. Report to the Alabama Historical Commission from The University of Alabama.

Oakley, Carey B. and G. Michael Watson

1977 Cultural Resources Inventory of the Jones Bluff Lake, Alabama River, Alabama. University of Alabama. Office of Archaeological Research. Report of Investigations 4.

Owen, Thomas M.

1921 History of Alabama Dictionary of Alabama Biography Vol. II. S.J. Clarke Publishing Co. Chicago, Illinois.

Palmer, Edward

1884 Unpublished field notes on file at the Alabama Archives and History. Montgomery, Alabama. 1960 Alabama Note: Made in 1883-1884. Alabama Historical Quarterly 22:260-26!. Montgomery.

Peebles, Christopher S.

1971 Moundville and Surrounding Sites: Some Structural Considerations of Mortuary Practices II. Society for American Archaeology. Memoir 25.

1987 The Rise and Fall of the Mississippian in Western Alabama: The Moundville and Summerville Phases, A.D. 100-1600. Mississippi Archaeology 22(1): 1-3.

Pickett, Albert J.

1851 History of Alabama. Walker and James, Charlestown.

Priestley, Herbert I.

1929 The Luna Papers. Books for Libraries Press. Freeport, New Jersey.

1936 Tristan de Luna. Conquistador of the Old South. Arthur H. Clarke Company. Glendale, California.

Sears, William H.

1959 An Investigation of Prehistoric Processes on the Gulf Coastal Plain. Report to the National Science Foundation from the University of Florida.

1977 Prehistoric Culture Areas and Culture Change on the Gulf Coastal Plain. In, Research Essays in Honor of James B. Griffin, Museum of Anthropology. University of Michigan. Anthropological Papers 61.

Sheldon, Craig T. and Ned J. Jenkins

2020 Artifacts of the Soto and Luna y Arellano Expeditions in Alabama. In Modeling Entradas: Sixteenth-Century: Assemblages in North America. Edited by Clay Mathers. University of Florida Press.

Sheldon, Craig T., Jr., David Chase, Gregory Waselkov, and Elisabeth Sheldon

1982 Cultural Resource Survey of Demopolis Lake, Alabama: Fee Owned Land. Report to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Mobile District from Auburn University. Auburn University Archaeological Monograph 6.

Shogren, Michael O.

1989 A Limited Testing Program at Four Mound Sites in Greene County, Alabama. Alabama De Soto Commission Working Paper 11.

Smith, Marvin T.

1976 The Route of DeSoto Through Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama: The Evidence from Material Culture. Early Georgia 4(1-2):27-48.

1982 Chronology from Glass Beads: The Spanish Period in the Southeast. 15 13-1670. Paper presented at the Glass Trade Bead Conference, Rochester Museum and Science Center.

1987 Archaeology of Aboriginal Culture Change in the Interior Southeast: Depopulation during the Early Historic Period. Ripley P. Bullen Monographs in Anthropology and History 6. Florida State Museum. Gainesville.

Smith Marvin T. and Mary Elizabeth Goode

1982 Early Sixteenth Century Glass Beads in the Spanish Colonial Trade. Cottonlandia Museum. Greenwood, Mississippi.

Steponaitis, Vincas

1980 Ceramics. Chronology, and Community Patterns at Moundville. A Late Prehistoric Site in Alabama. Ph.D. Dissertation. University of Michigan.

Stowe, Noel R.

1971 University of South Alabama – Archaeological Research Association of Alabama. Inc. Site Survey of South Alabama. Report on file with the Archaeological Research Association of Alabama, Inc.

1978 A Preliminary Cultural Resources Literature Search of the Mobile Tensaw Bottomlands. Report on file, National Park Service, Tallahassee, Florida.

1985 The Pensacola Variant and the Bottle Creek Phase. The Florida Anthropologist 38(1-2). Stowe, Noel R., Richard Fuller, Amy Snow, and Jennie Trimble.

1982 A Preliminary Report on the Pine Log Creek Site (1Ba462). Report on file, University of South Alabama Archaeology Lab. Mobile, Alabama.

Stubbs, J.D., Jr.

1982 A Preliminary Classification of Chicasaw Pottery. Mississippi Archaeology l7(2):50-56.

1982 The Chickasaw Contact with the La Salle Expedition. In La Salle and His Legacy: Frenchmen and Indians in the Lower Mississippi Valley. P.K. Galloway (ed). University Press of Mississippi. Jackson.

Sturtevant, William C.

1985 Forward: Final Report of the United States De Soto Expedition Reprint in Classics of Smithsonian Anthropology: viii.

Swanton, John R.

1936 Minutes of the (Second) Meeting of the De Soto Commission. Tampa, Florida, May 4-5 1936. Inclusive Transcript, 46 pages, in MS 4465, Box 1, Folder 1, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

1922 Early History of the Creek Indians and Their Neighbors. Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 73. Washington D.C.

1946 Indians of the Southeastern United States. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin

1985 Final Report of the United States De Soto Expedition Commission. Reprint by the Smithsonian Institution from the 1939 original.

Thomas, Cyrus

1894 Report of the Mound Explorations of the Bureau of Ethnology. Smithsonian Institution. Bureau of Ethnology Annual Report 1890-198 1(12).

Trickey, E. Bruce

1958 A Chronological Framework for the Mobile Bay Region. American Antiquity 23(4).

Trickey, E. Bruce and Nicholas H. Holmes, Jr.

1971 A Chronological Framework for the Mobile Bay Region. Journal of Alabama Archaeology 17(2).

Varner, John and Jeannette Varner

1951 The Florida of the Inca. University of Texas Press. Austin, Texas.

van Hoose, Natalie

2024 Hernando de Soto Archaeologists Gather for a Meeting of the Minds. Stones and Bones, The Newsletter of the Alabama Archaeological Society Vol. 66,Sept.-Oct. 2024. (excerpt from the fall 2024 issue of American Archaeology Vol. 28: No. 3.)

Vierra, Bradley J.

1987 A Sixteenth Century Spanish Campsite in the Tiguex Province. Museum of New Mexico Laboratory of Anthropology Note 475.

Waselkov, Gregory A.

1981 Lower Tallapoosa River Cultural Resource Survey. Report to the Alabama Historical Commission from Auburn University.

Waselkov, Gregory A., Brian M. Wood, and Joseph M. Herbert

1982 Colonization and Conquest: The 1980 excavations at Fort Toulouse and Fort Jackson, Alabama. Auburn University Archaeological Monograph 4.

Willey, Gordon R.

1949 Archaeology of the Florida Gulf Coast. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collection 113. Washington D.C.

Wimberly, Stephen B.

1960 Indian Pottery from Clarke County and Mobile County, Southern Alabama. Alabama Museum of Natural History Museum Paper 36. University, Alabama.

Archives of the Indies, Seville, Spain